According to the German Alzheimer’s Association (DAlzG), every 100 seconds, a person in Germany falls ill with dementia. Most of them suffer from a form of dementia known as Alzheimer’s disease. There are more than 300,000 new cases every year. The exact cause is still unclear. Until now, the disease has been diagnosed based on symptoms, lumbar puncture or imaging methods such as positron emission tomography (PET). This is not only unpleasant and time-consuming for the patient, but this form of diagnosis is also very cost-intensive.

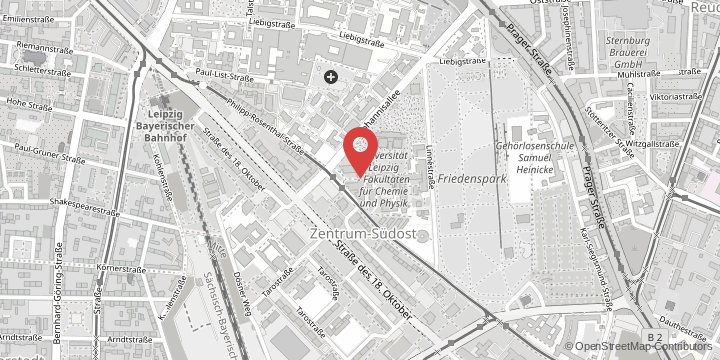

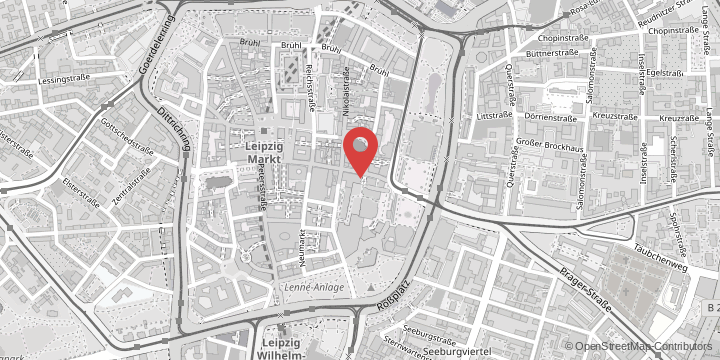

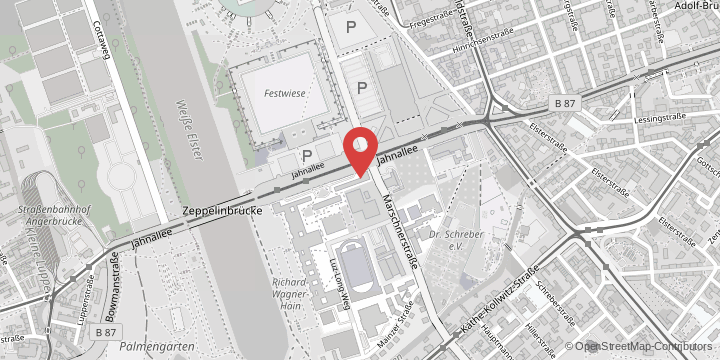

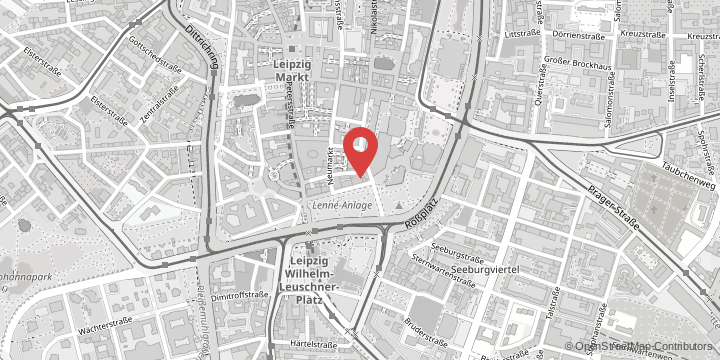

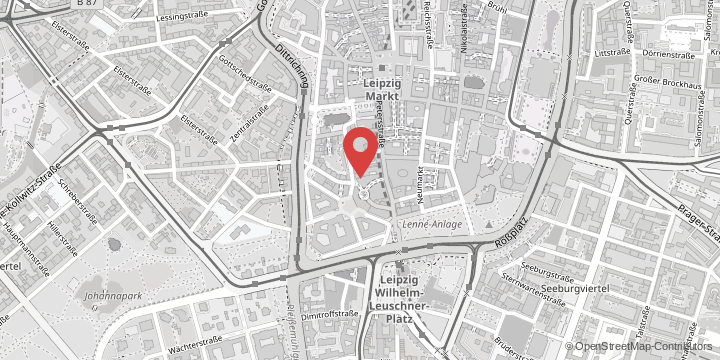

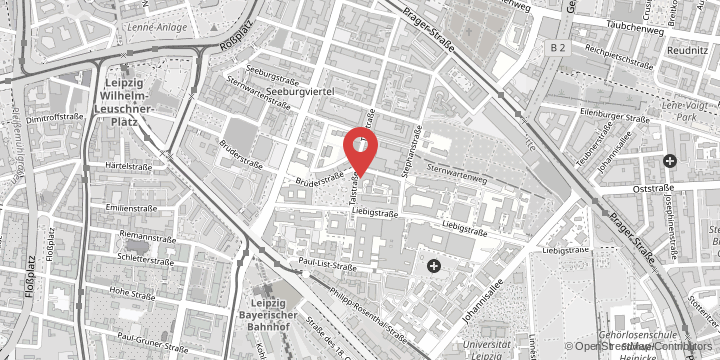

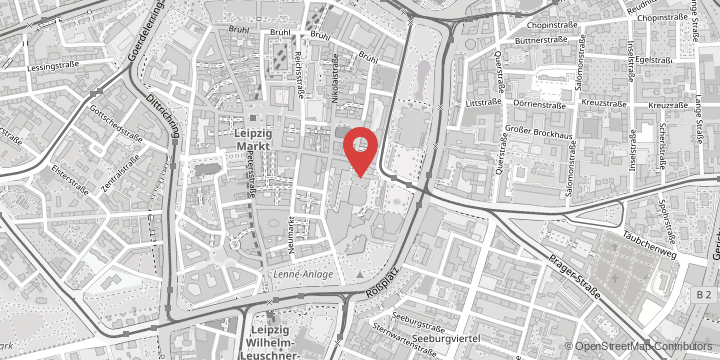

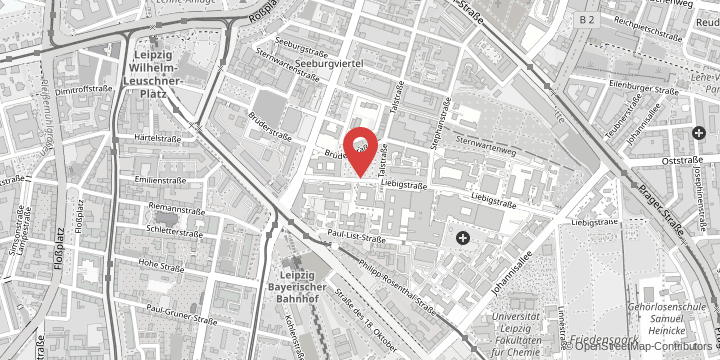

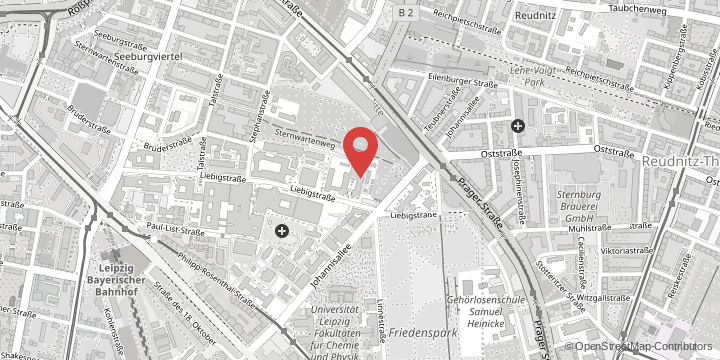

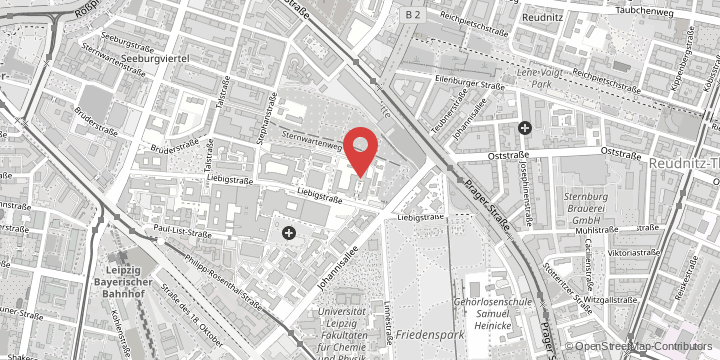

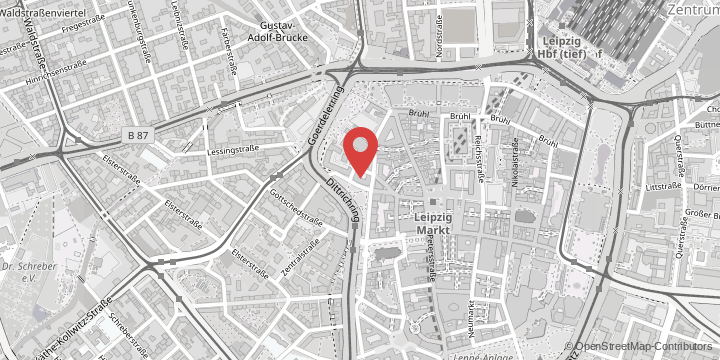

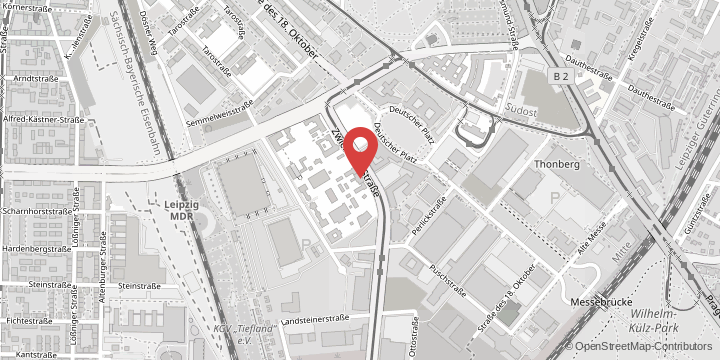

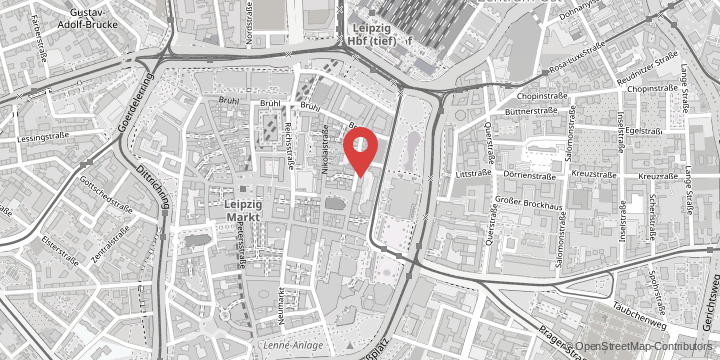

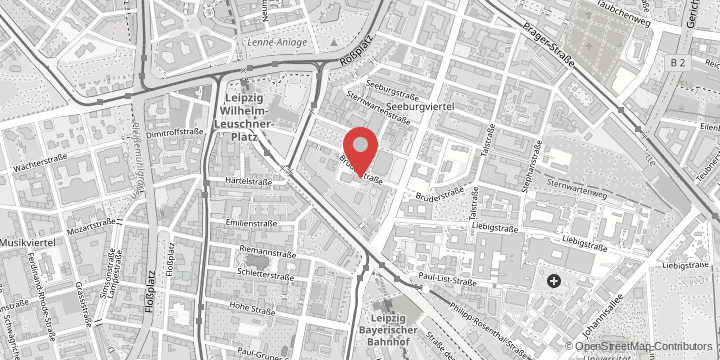

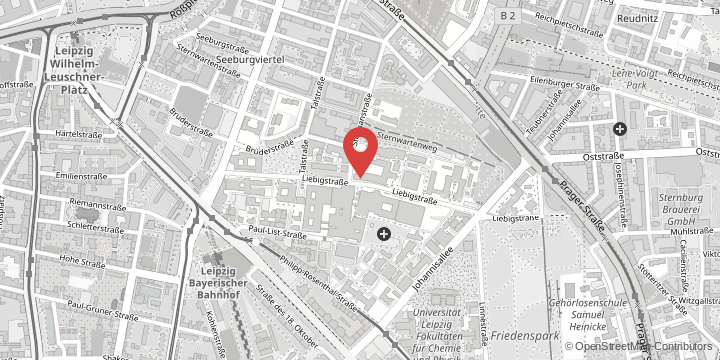

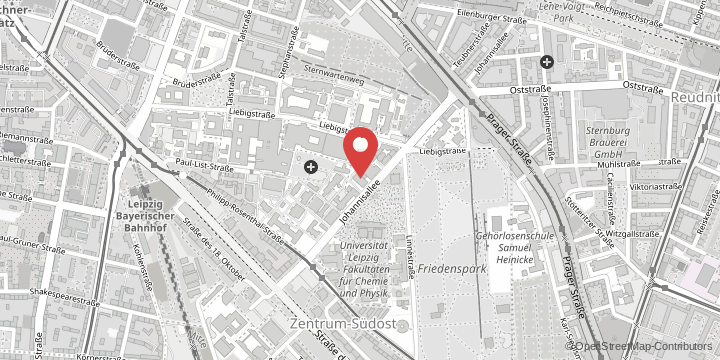

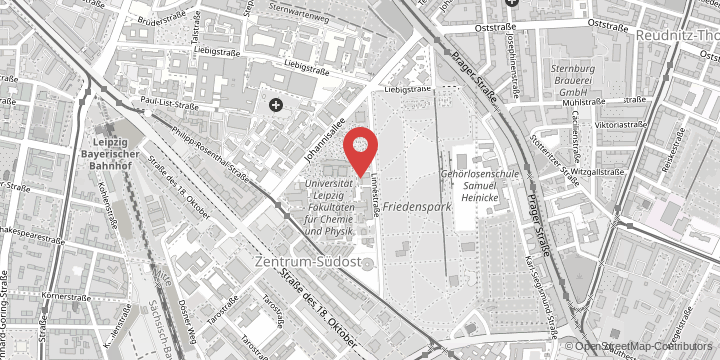

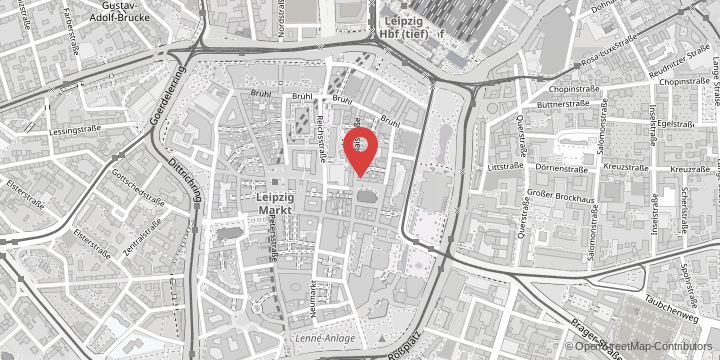

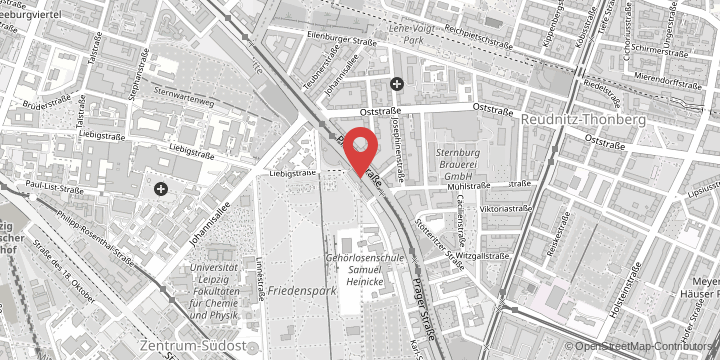

A blood test developed over the past 20 years at Leipzig University can detect the disease much more easily and efficiently. Blood is taken from the patient, then the white blood cells are stimulated in the laboratory using certain substances that trigger cell division. The cells of people with Alzheimer’s respond differently to those of healthy patients. “This disease-specific cell response means we can make a conclusive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Our clinical trials conducted in recent years have clearly shown this,” explained Professor Thomas Arendt, Director of the Paul Flechsig Institute for Brain Research. The US company Amarantus BioScience has now acquired the exclusive licence to use this test from the University. The company plans to refine the test in the future and use it as the basis for determining a diagnostic biomarker. The aim is to detect the disease at an early stage so that appropriate therapy can be started immediately. “We are of course delighted that our research is now being introduced into clinical practice. We will continue to work on further simplifying the test so that it can eventually be carried out by general practitioners,” said Arendt.

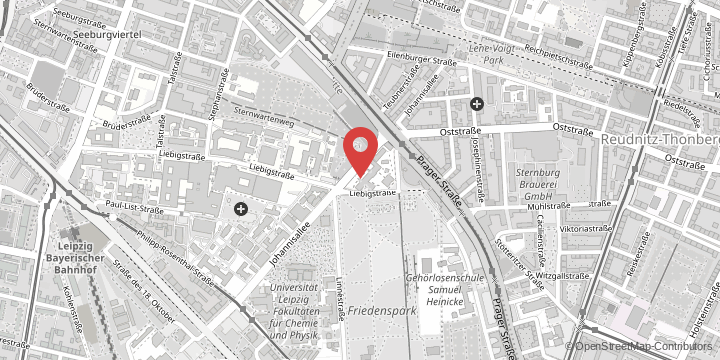

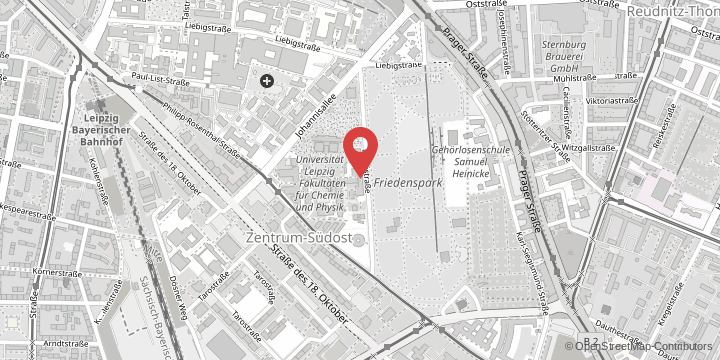

Professor Arendt and his team have spent nearly 40 years researching Alzheimer’s disease. In the 1980s, they were involved in the discovery that established the basis for the only possible treatment to date: the researchers observed that neurones which use the semiochemical acetylcholine to transmit signals die off in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. Professor Arendt suspects a disorder in the activation of these nerve cells to be the cause of Alzheimer’s disease. “In my opinion, the cellular system of cell division is damaged in this disease. Nerve cells don’t actually divide. However, in Alzheimer’s disease, the molecular switch is reversed and cell division is reactivated at the wrong time and in the wrong place,” explains Arendt. Gene therapy could stop these division processes, reactivate cell protection and thus prevent cell death.