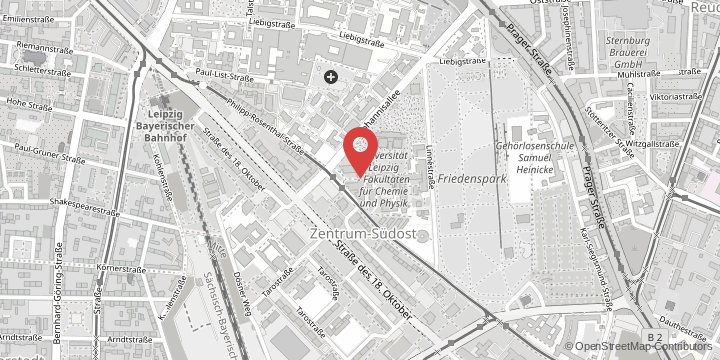

“We scientists still don’t yet fully understand how the molecular mechanisms of learning and memory really work. We know that nerve cells communicate with each other via contact points known as synapses. Synapses are like one-way streets, with the sending cell releasing a chemical messenger, or neurotransmitter, which is then recognised by the receiving cell. When we learn something – so when we absorb information in order to retrieve it again later on – this affects the amount of neurotransmitter released,” explains Hallermann. Here scientists refer to so-called ‘presynaptic plasticity’, a phenomenon currently still poorly understood. Using two methods, Hallermann now aims to solve the mystery of presynaptic plasticity, or the temporary deformation of nerve endings. On the one hand he will investigate the function of nerve endings, and on the other their structure. The Faculty of Medicine’s Carl Ludwig Institute for Physiology offers the ideal setting for this, allowing certain high-resolution techniques to be used in nerve ending research for the first time ever.

Electrophysiological measurements will serve to analyse nerve ending function. Hallermann’s research team has developed a novel technique that uses ultra-fine glass capillaries to investigate the release of neurotransmitters directly at the nerve endings. Explaining the scientific method which will be applied in animal models, the scientist said: “We position tiny glass capillaries directly on the nerve endings, which are smaller than a thousandth of a millimetre in size. This enables us to measure directly how much of the neurotransmitter is released by the cell.”

The second method is a high-resolution microscopic procedure that temporally maps the deformation of nerve endings. The EU funding means it will now be possible to purchase the necessary microscope. A research team comprising ten scientists will assist Hallermann in his attempt to uncover the hidden secrets of learning and memory. “If we learn to understand the processes of molecular and biophysical learning mechanisms in their complexity, we can also better understand their dysfunctions. The findings could pave the way for new approaches in the treatment of neurological diseases such as dementia and Alzheimer’s,” said Professor Hallermann, explaining the long-term goal of his research. He is supported by the European Research Council with its ERC Consolidator Grant, which will allow him to further expand his research activity. “I am delighted about this honour,” said the 44-year-old neurophysiologist. “It would not have been possible without the good team work, both within my working group and in Leipzig as a whole.”

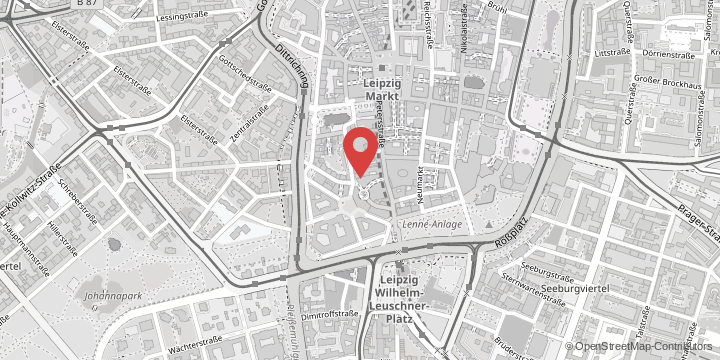

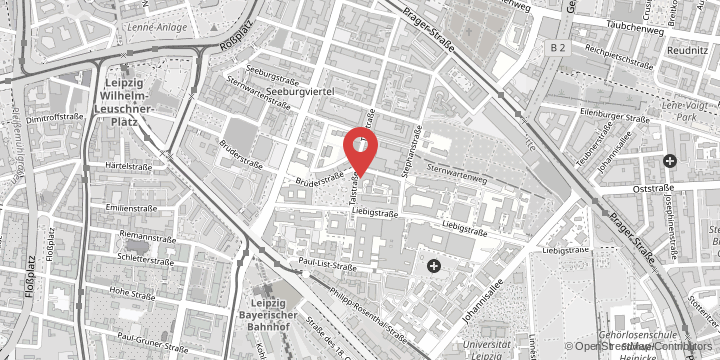

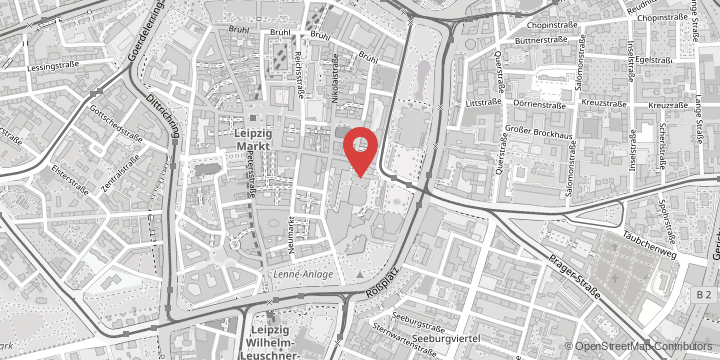

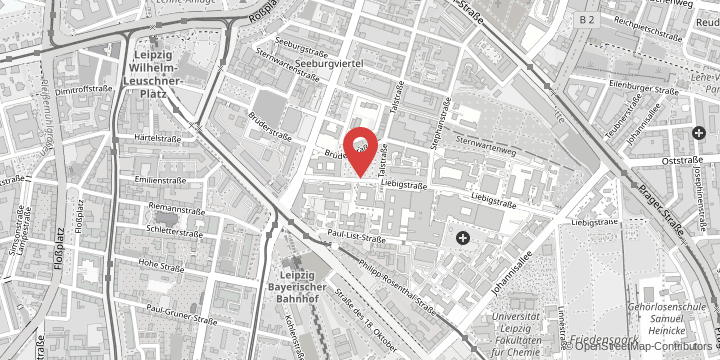

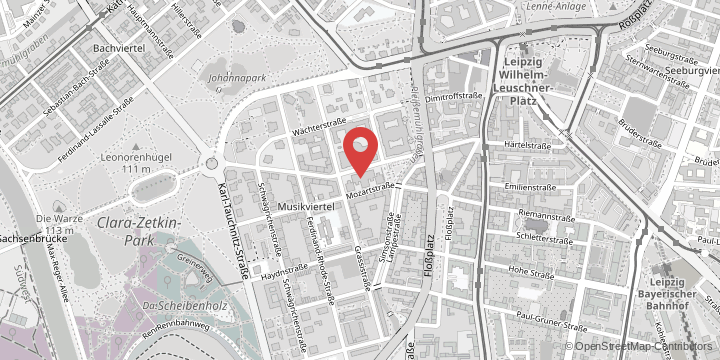

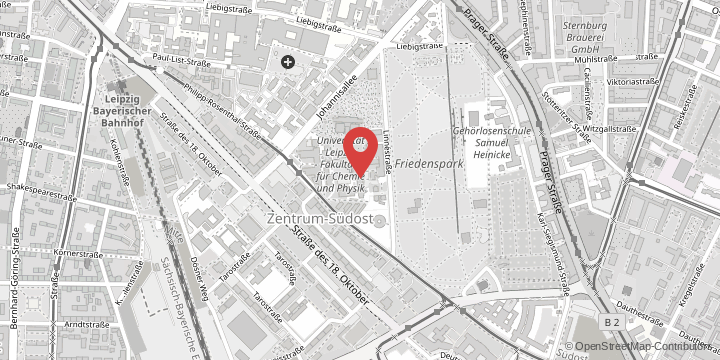

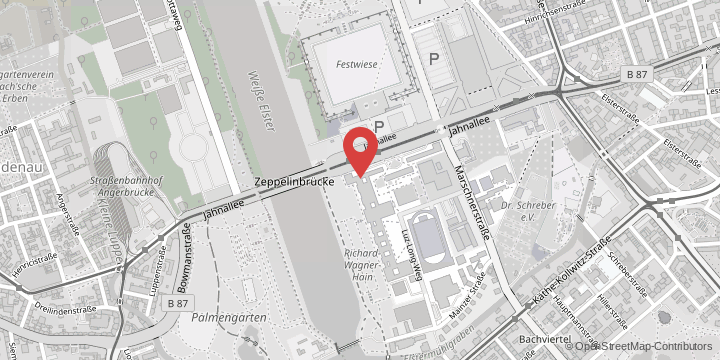

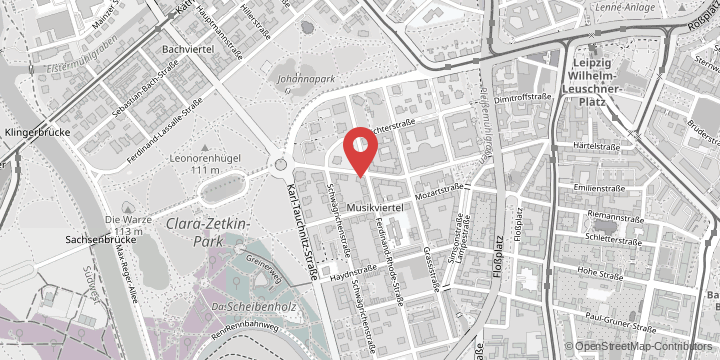

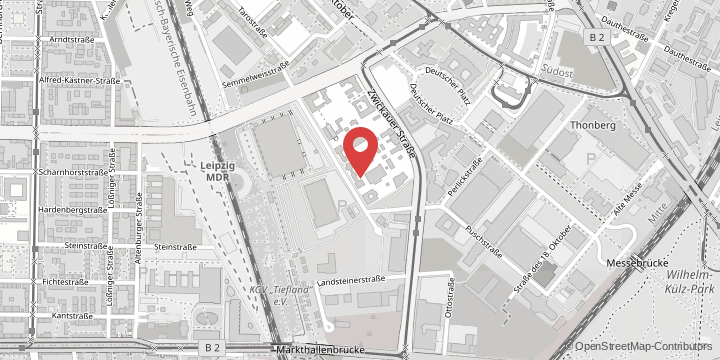

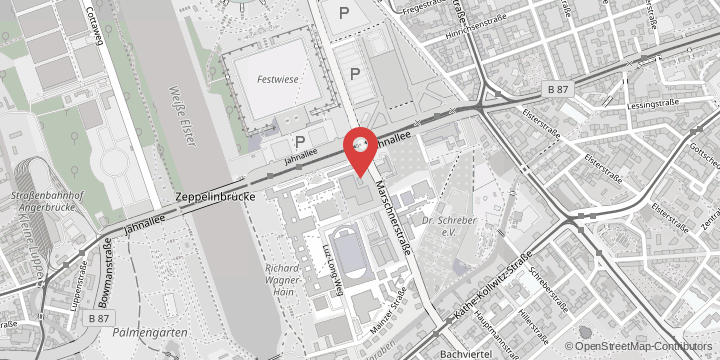

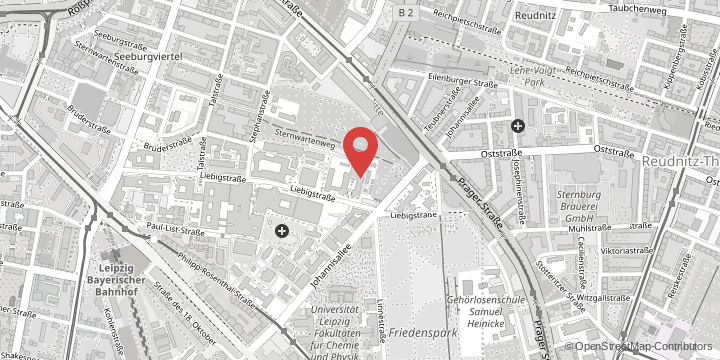

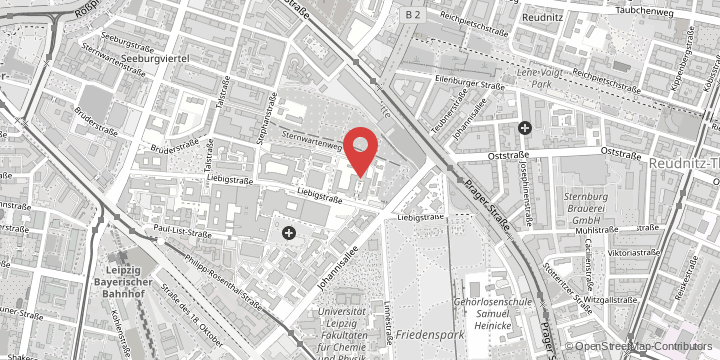

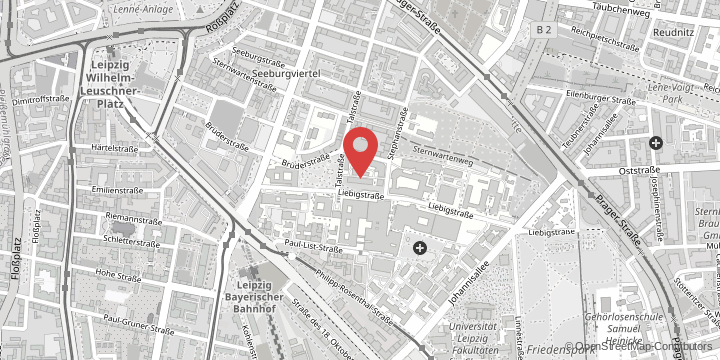

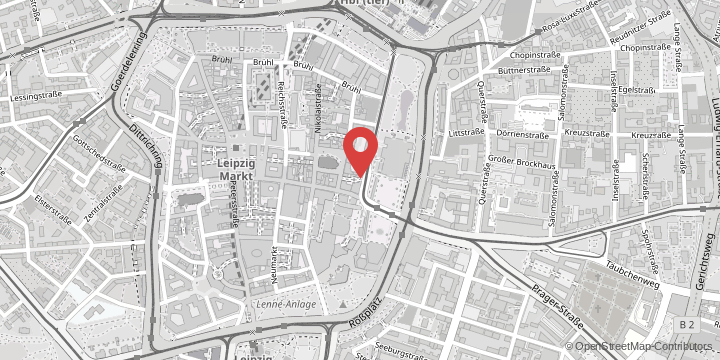

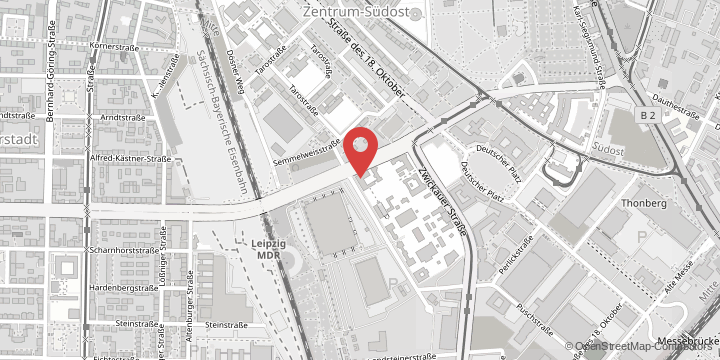

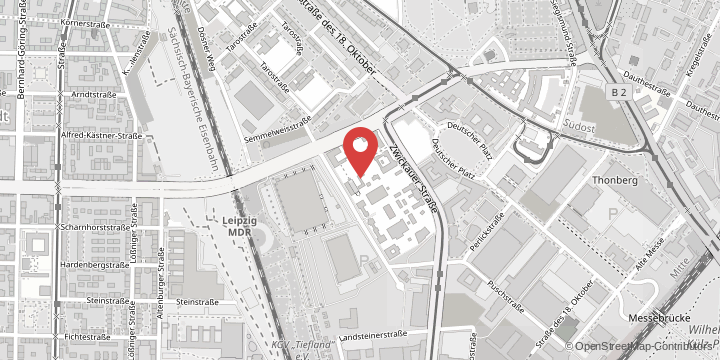

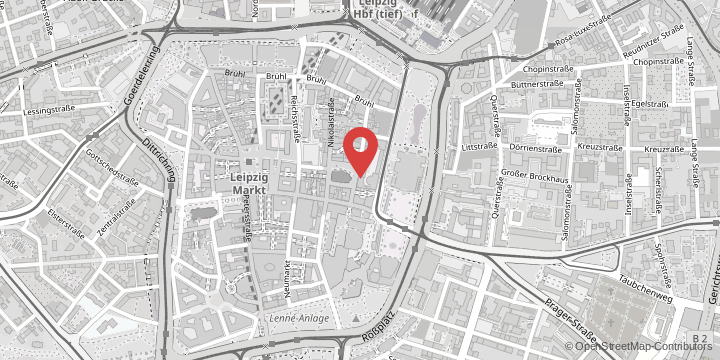

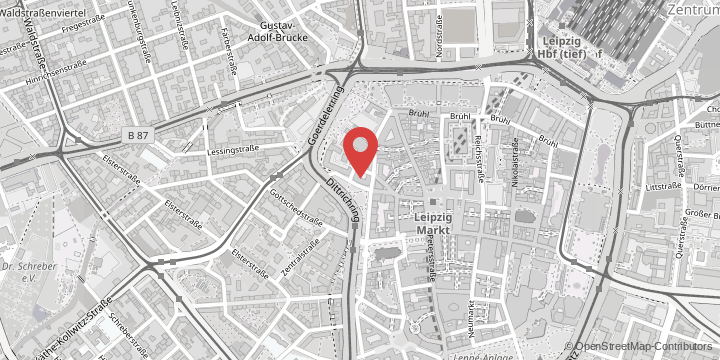

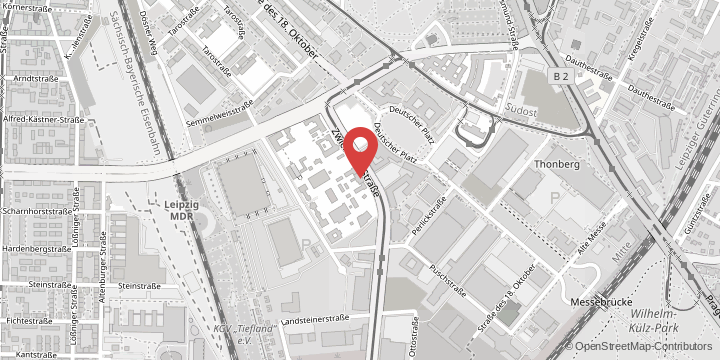

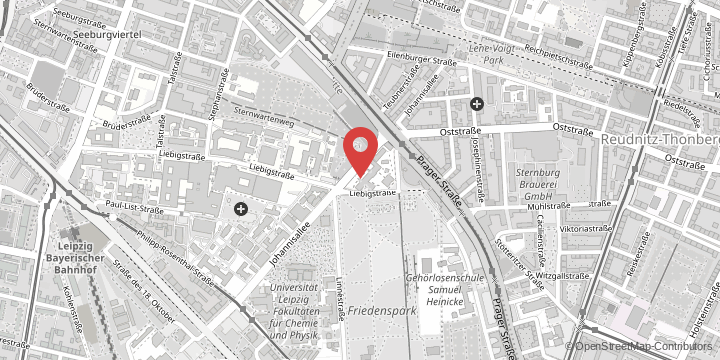

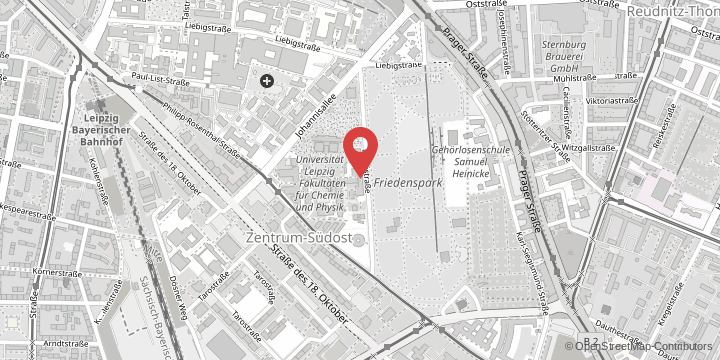

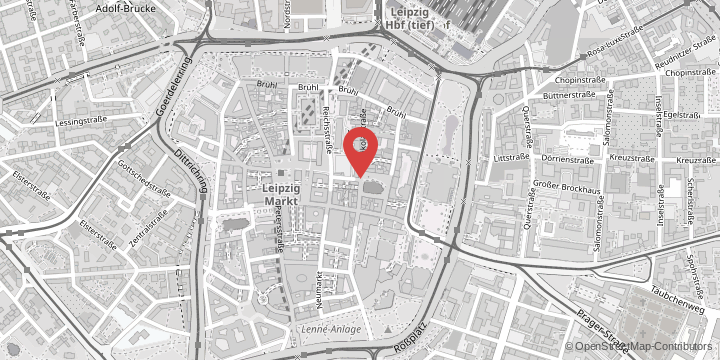

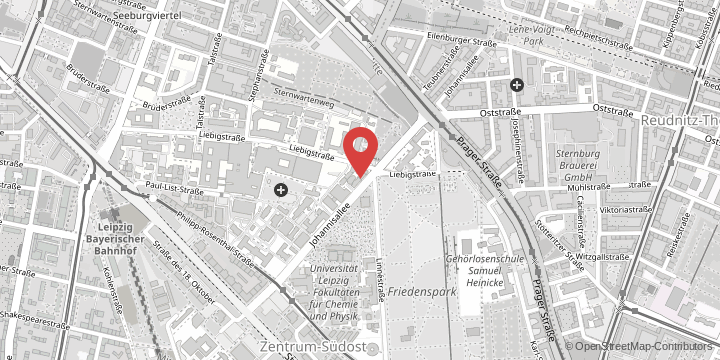

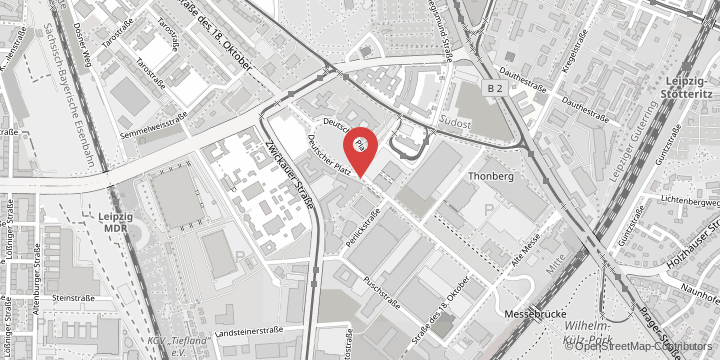

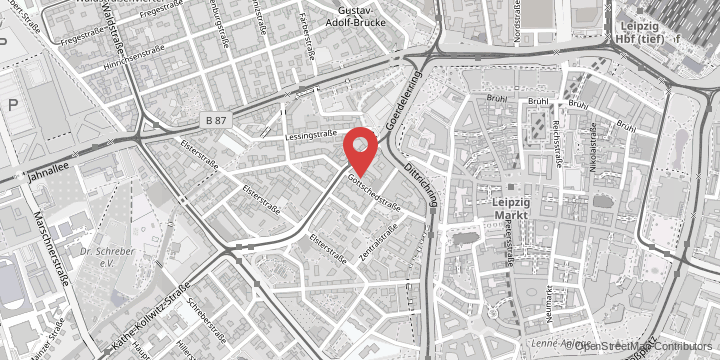

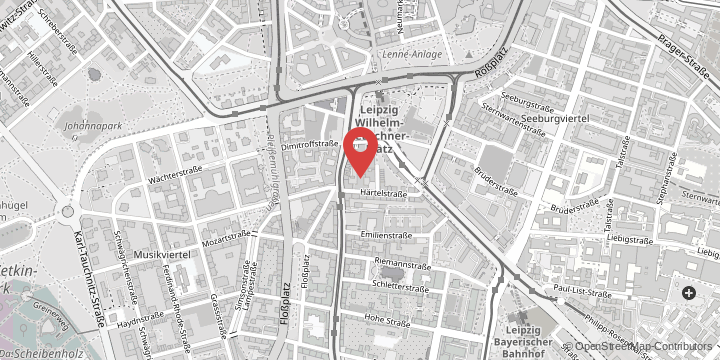

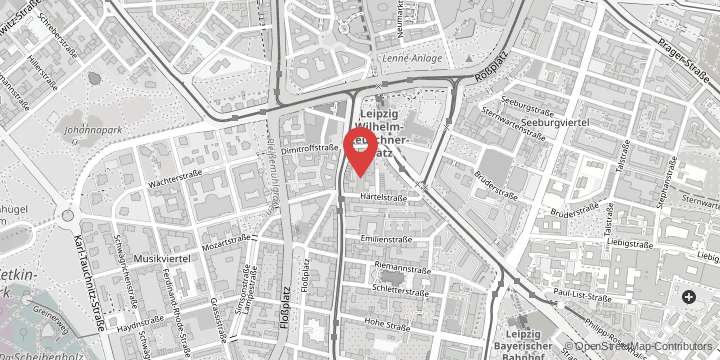

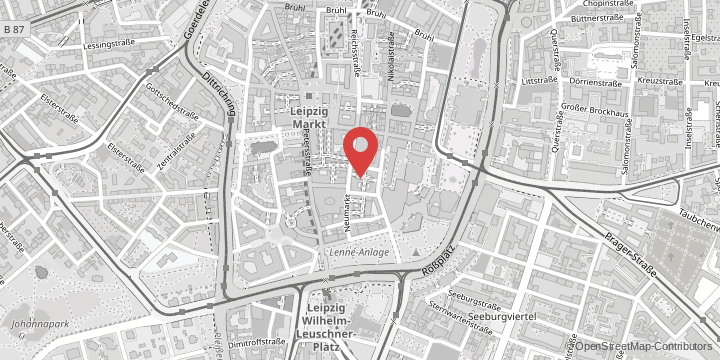

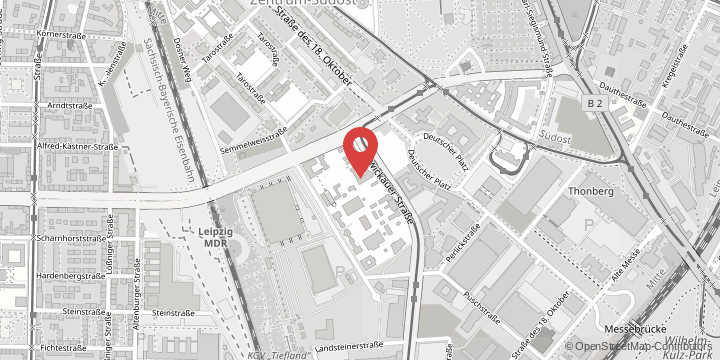

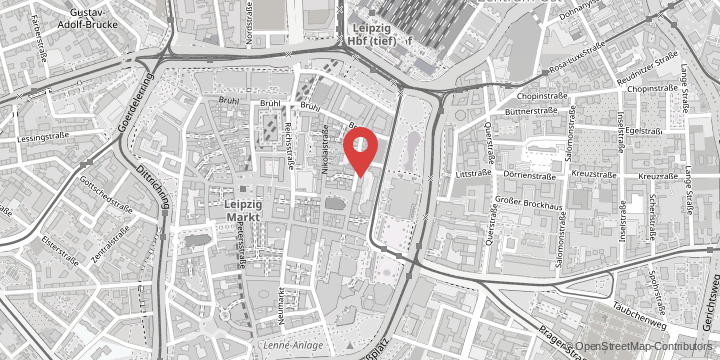

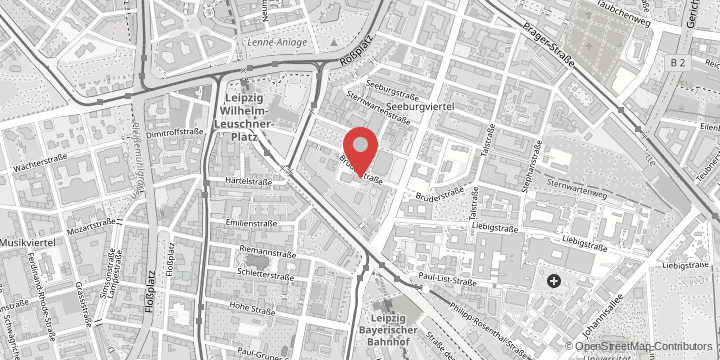

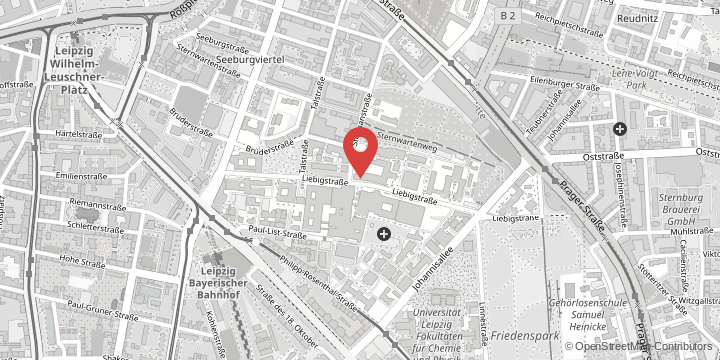

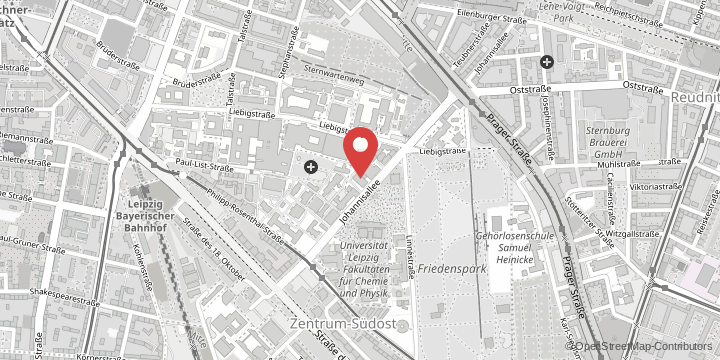

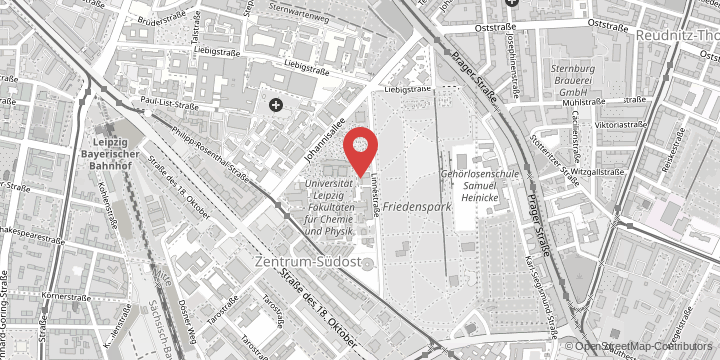

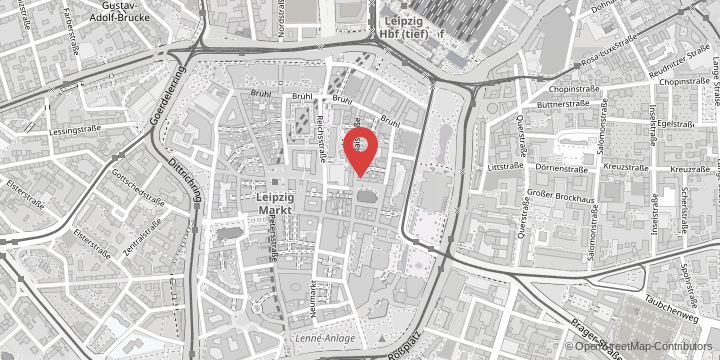

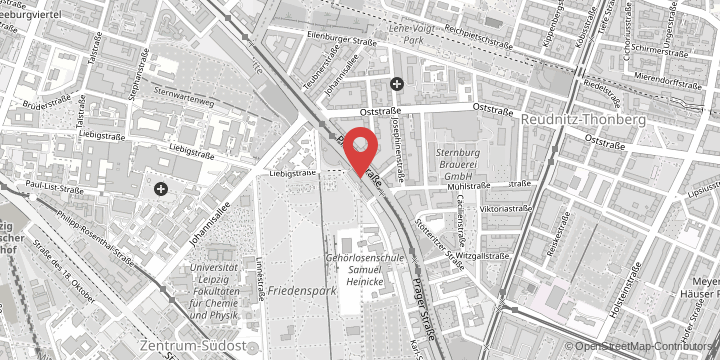

Professor Stefan Hallermann studied physics and medicine in Munich and Freiburg. Born in Würzburg, his scientific career involved periods in Canberra, Würzburg, Leipzig and Göttingen, before he ultimately returned to Leipzig, where he has been Professor of Neurophysiology at the Carl Ludwig Institute since 2013. The German Research Foundation’s (DFG) Heisenberg Programme paved the way for his Heisenberg professorship at the Faculty of Medicine, which culminated in his taking over the Chair of Physiology in 2018. The funding provided by the ERC Consolidator Grant from 2020 to 2025 will boost the Faculty of Medicine’s Brain and Psychological Disorders research profile area.