Illegitimacy, infanticide, and child abandonment in 18th century Frankfurt

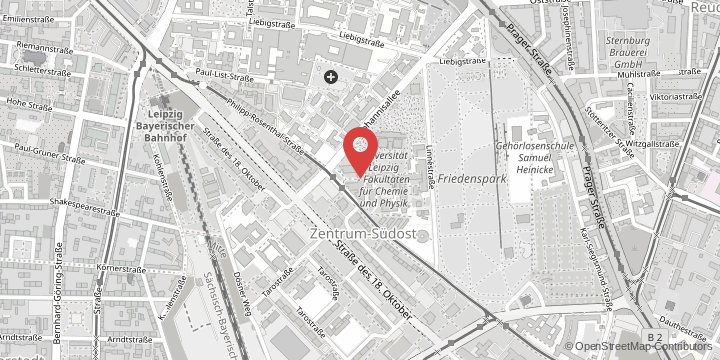

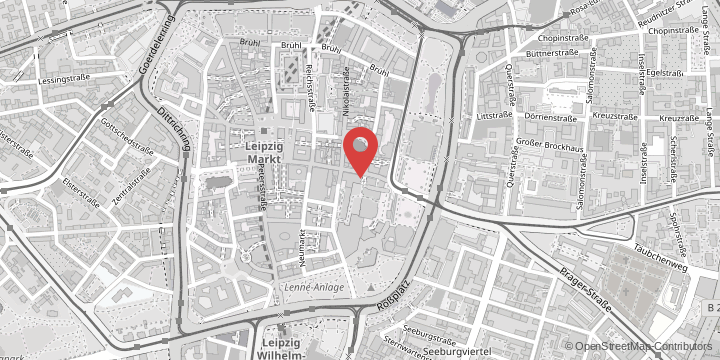

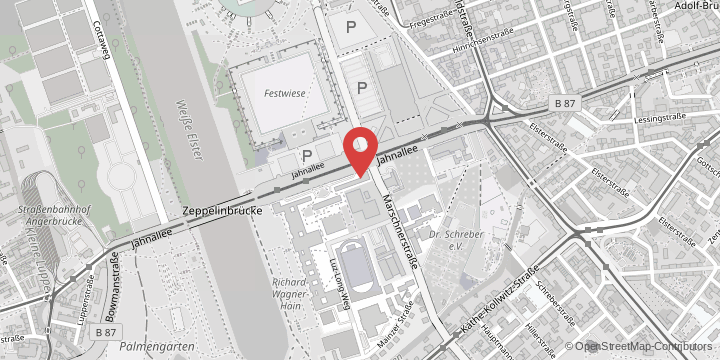

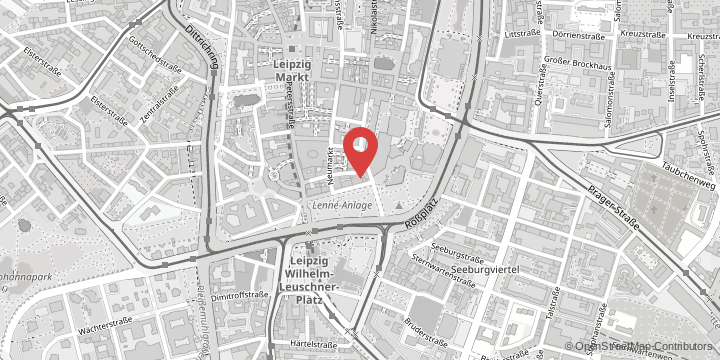

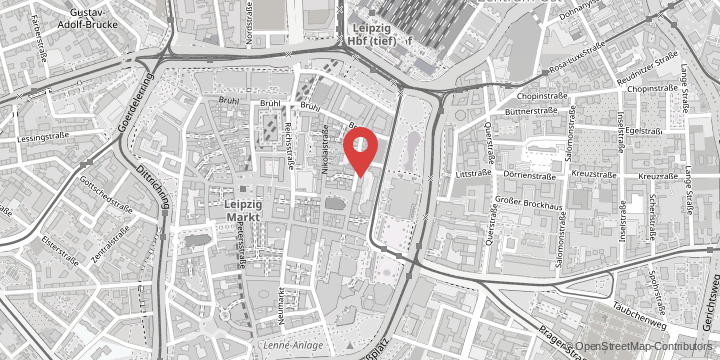

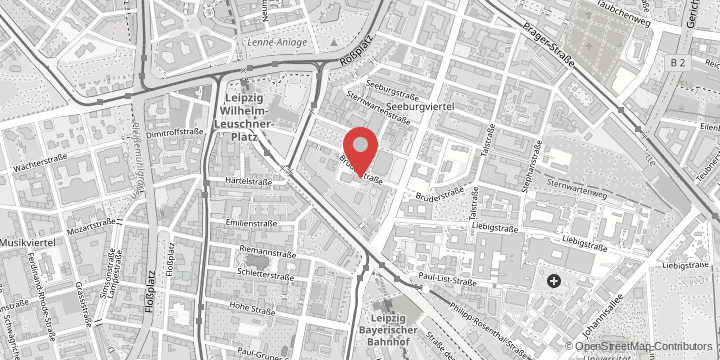

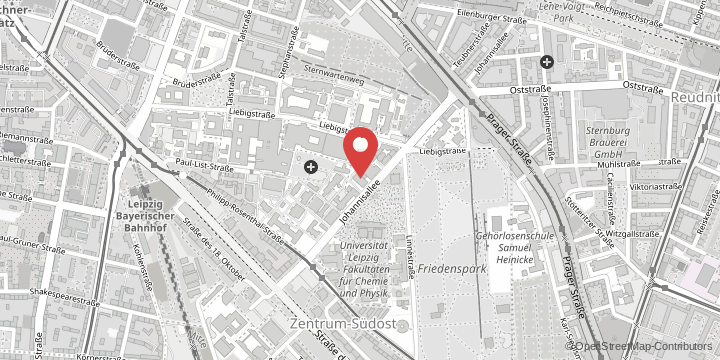

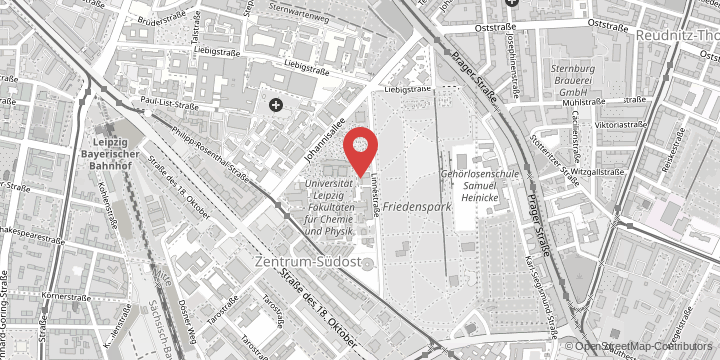

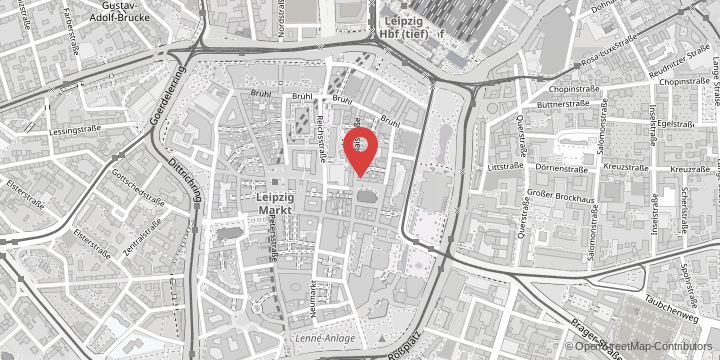

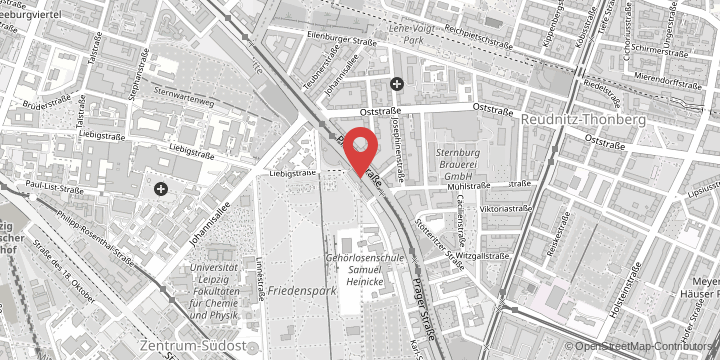

Lecture by historian Dr. Jeannette Kamp (Leiden)

“Vulnerability to pregnancy is women’s Achilles’ heel” (Moch 2003). In her groundbreaking work on European migration – already more than twenty years ago – Leslie Page Moch drew attention to the relationship between female migration and sexuality. Migrant women contributed disproportionately to urban illegitimacy rates and featured more prominently among those accused of and prosecuted for infanticide or child abandonment. As Moch, and many scholars after her, have pointed out, these figures are not a result of different sexual attitudes or behavior of migrant and local women. Instead, they are a result of the lack of social support networks that allowed local women to enforce marriage or child support judicially or extra-judicially. In this talk I want to argue that these power differences in getting justice were not just shaped by the varying strength of support networks, but also need to be studied in a broader context of policing migration by early modern societies. The case of 18th- century Frankfurt shows that the legal status of offenders heavily impacted women’s legal agency and prosecutions outcomes.

Although a large variety of sexual acts were considered as crimes, in the eighteenth century Frankfurt’s authorities increasingly focused on the prosecution of illegitimacy, which became ever more linked to the regulation of migration an poor relief rather than morality. It is telling that in 1755 Frankfurt’s city council issued an ordinance to expel all unmarried foreign women together with their children. Preferably, they were expelled while still pregnant, to avoid that the city would have to pay the costs of childbirth that these women would probably be unable to afford themselves. Even so, migrant women who had become pregnant out of wedlock were not necessarily left defenseless and their cases show. Women had the opportunity to claim financial compensation for the expenses of childbirth, demand damages for her defloration (if she was a virgin, of course), enforce alimony payments from the child’s father or even file a suit to force him to fulfil broken marriage promises. Still, for many women who became pregnant out of wedlock, the consequences were high—especially if they were expelled. To some women the threat of prosecution could lead to desperate measures, including infanticide. Still, women did make use of the courts and accommodated them to their own needs. By doing so, even if it was from a subordinate position, women shaped the institutions as well.

Author: Julia Schmidt-Funke