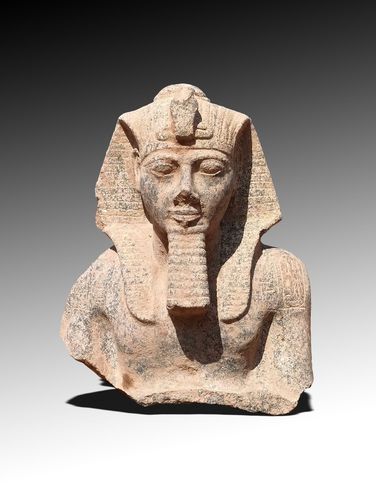

The basalt blocks uncovered during this 18th research campaign in the sun temple of Matariya reflect the rise of the regions of Lower Egypt, including the representation of the region of Heliopolis itself. “The inscriptions provide an insight into the date when the temple was founded in the early summer of 366 BC, the dimensions of the temple, and the materials used. A number of unfinished blocks suggest that construction work abruptly ended following the king’s death and did not recommence,” said Raue. This would make it one of the last, if not the final major structure built after a good 2400 years of continuous construction work by the kings of Egypt at the place where the world was created. Further architectural elements came from the time of Rameses II (1279 to 1213 BC) and his son Merneptah (1213 to 1201 BC). The former splendour is also illustrated by the discovery of a jasper inlay dating from around 1300 BC. “The life-size representation of Sethos II – a grandson of Rameses II who reigned from 1204 until 1198 BC – is a masterpiece of ancient Egyptian rose granite sculpture,” said Raue. From the period of use between the 4th and 2nd century BC, there were finds from workshops that produced relief models, amulets and shabti funerary figures.

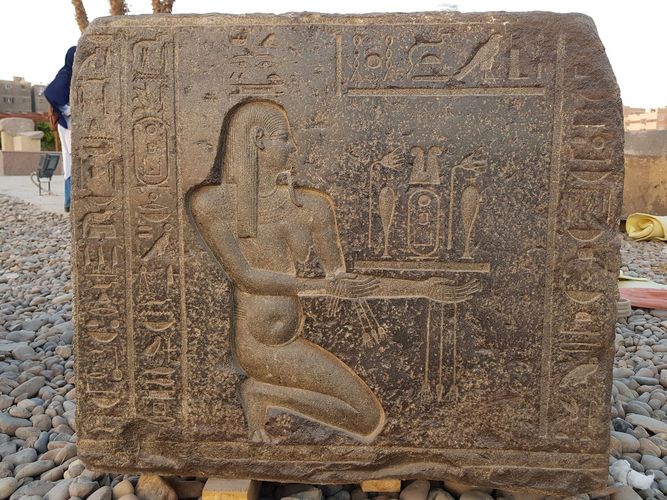

A number of revealing components and statue fragments were discovered in the vicinity of the still-standing obelisk of Heliopolis. These would have been used in the temple, as would large offering table altars made of quartzite and alabaster as well as a fragment of a baboon statue. There were also fragments of quartzite statues of Rameses II, an obelisk fragment from the time of King Osorkon I as well as a sanctuary for the deities Shu and Tefnut from the time of Psamtik II. “In this area, too, it is thus possible to demonstrate the ongoing commitment of the Egyptian pharaohs to the god of the sun and creation. The abandonment of this vast temple complex several centuries before the Christianisation of the country is still a mystery,” emphasised Dr Ashmawy. The excavation campaign was made possible by the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Donation Eckhard Sambach, the Gerda Henkel Foundation and further donations.

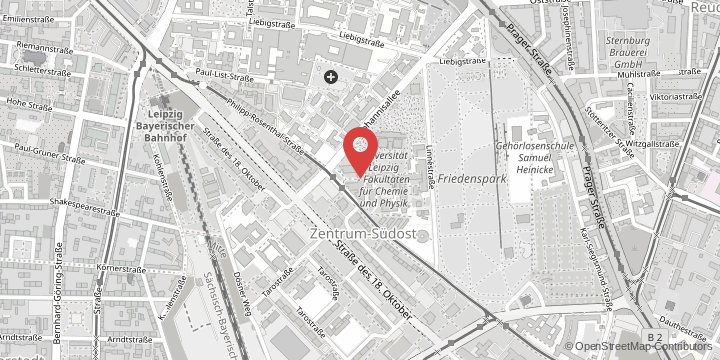

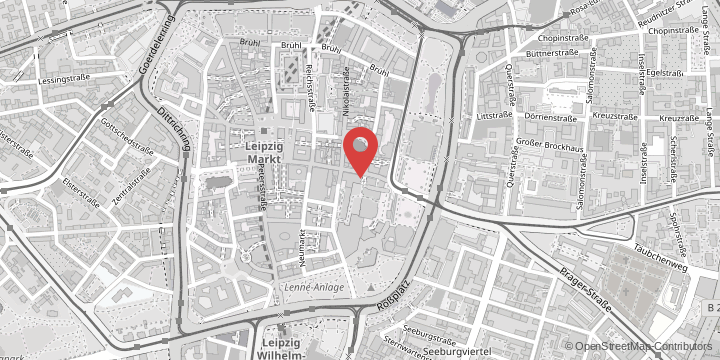

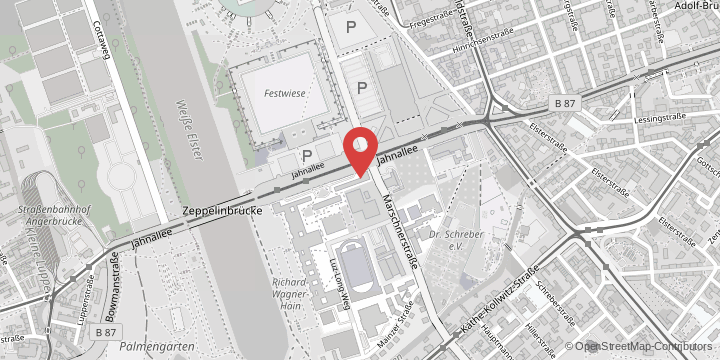

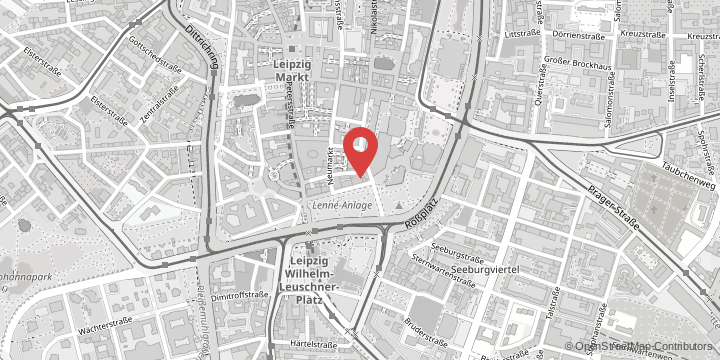

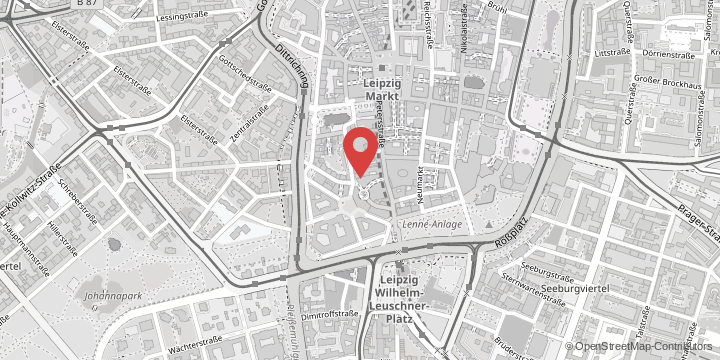

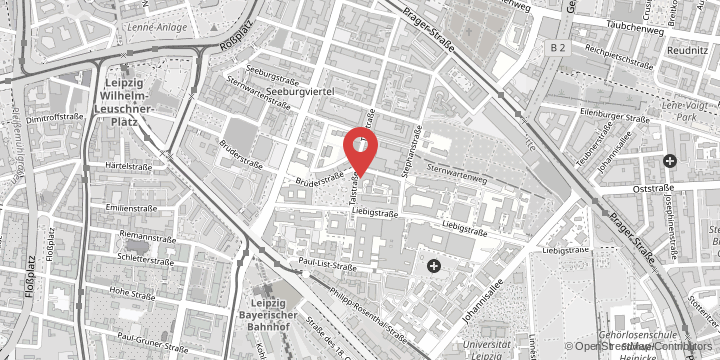

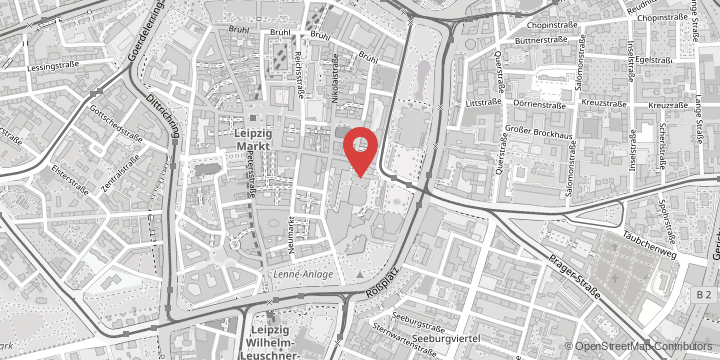

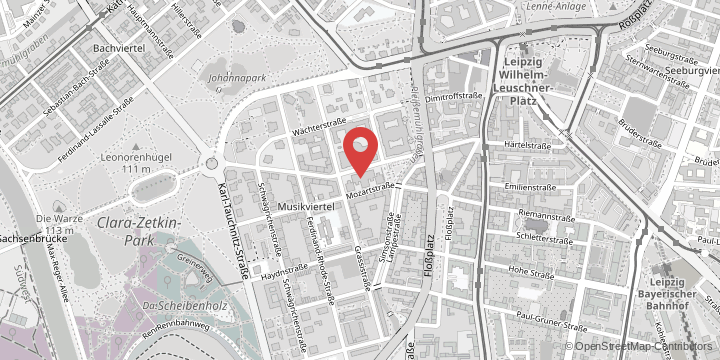

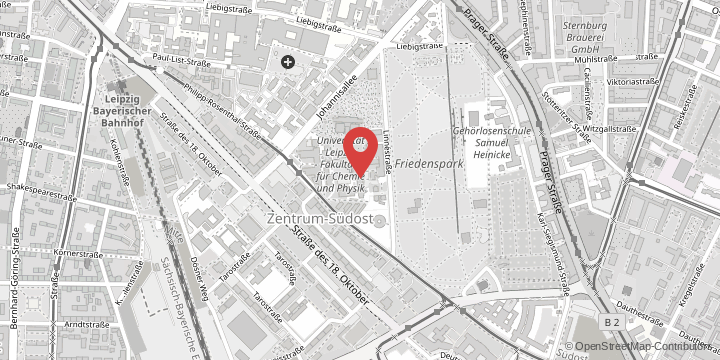

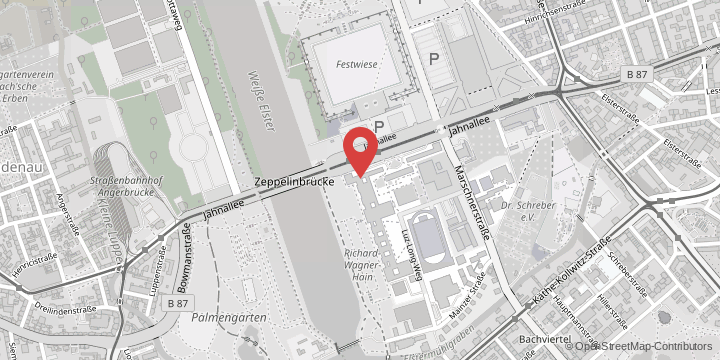

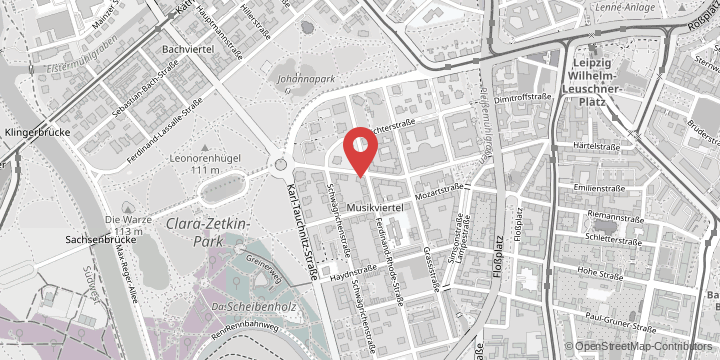

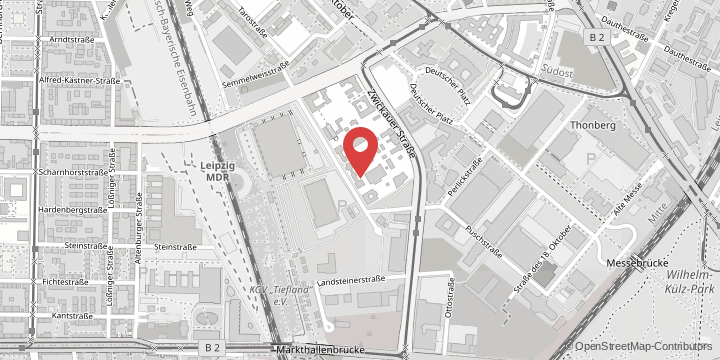

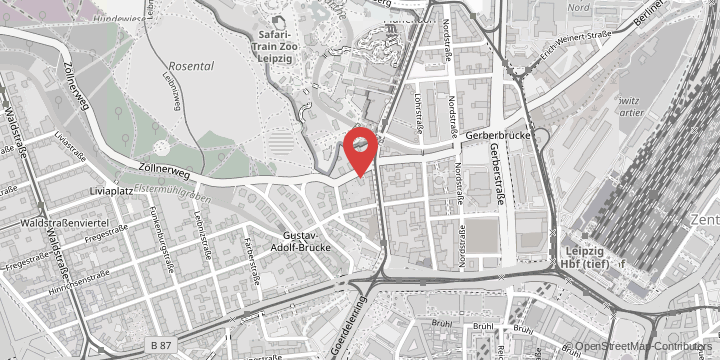

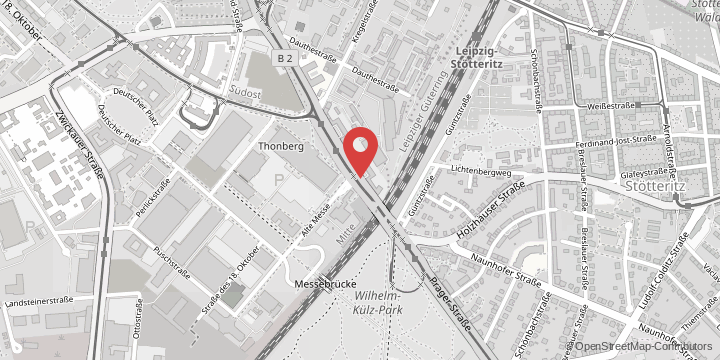

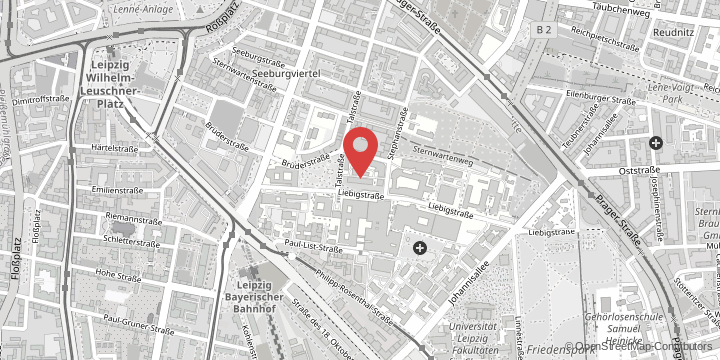

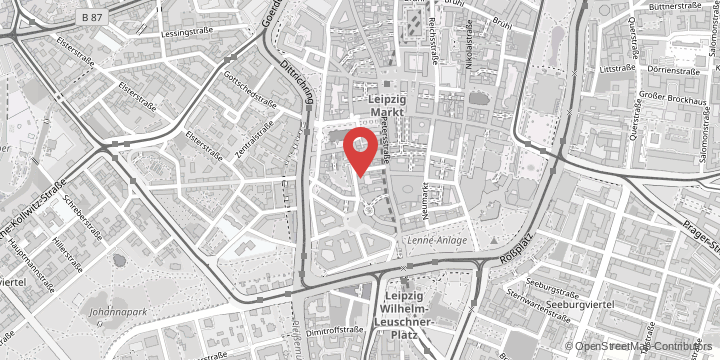

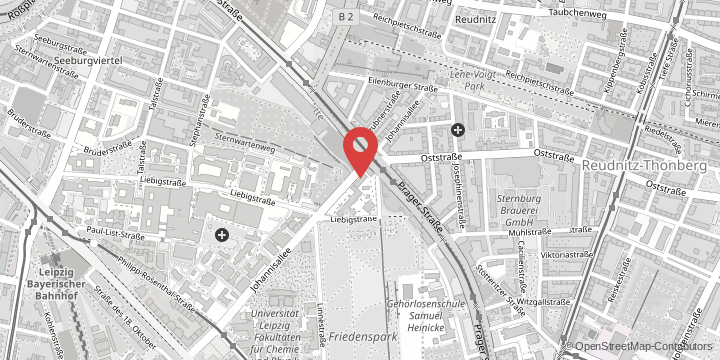

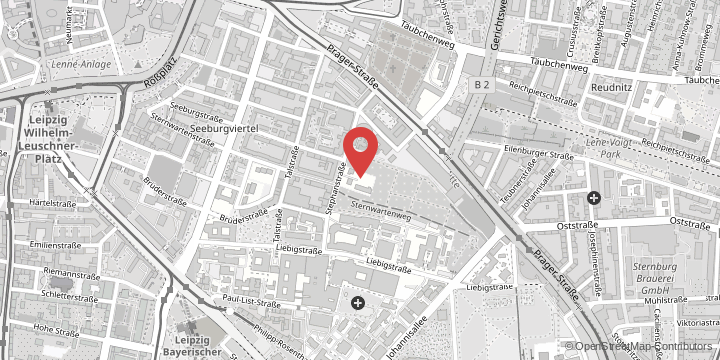

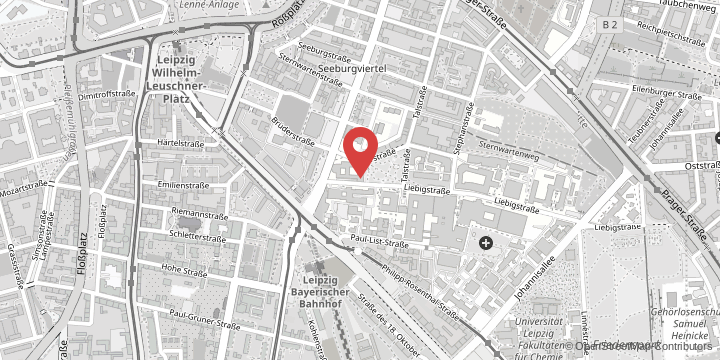

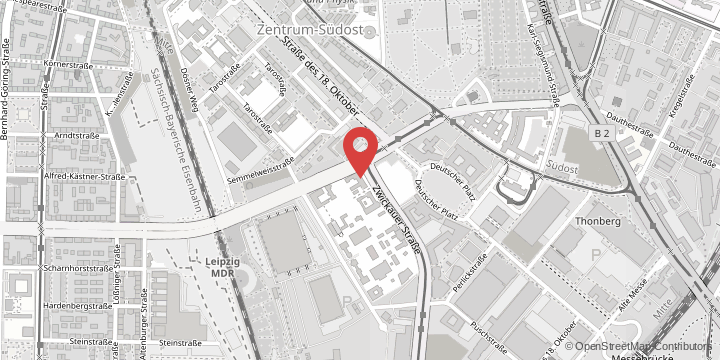

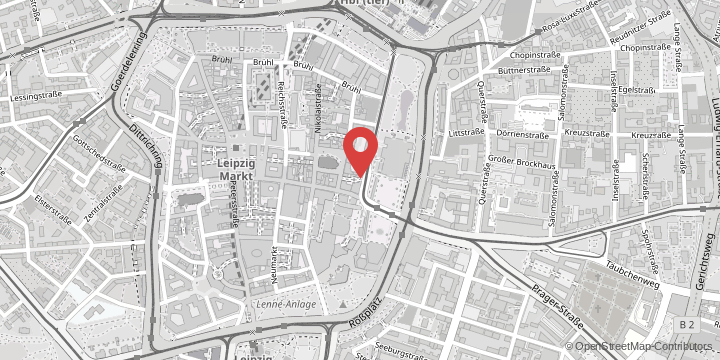

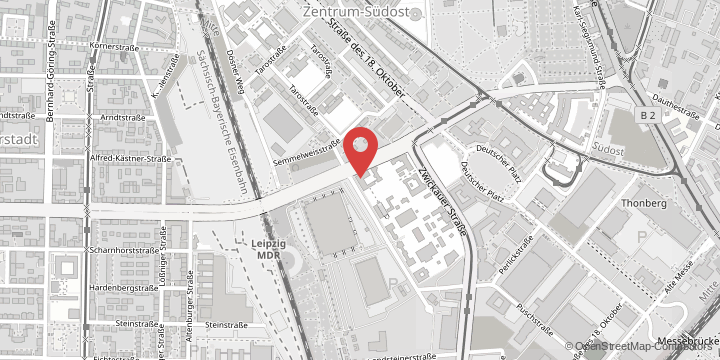

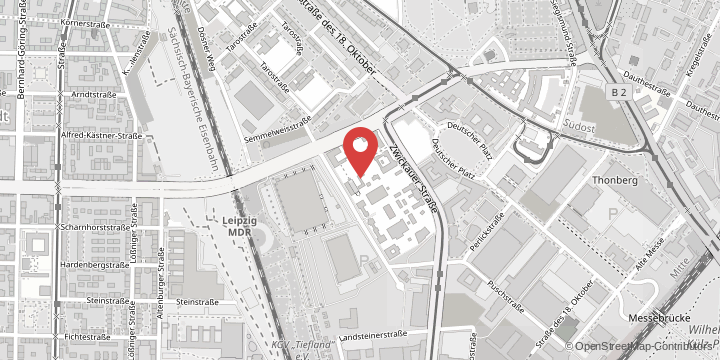

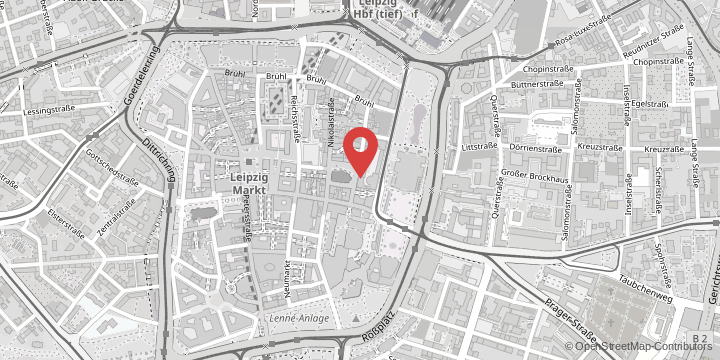

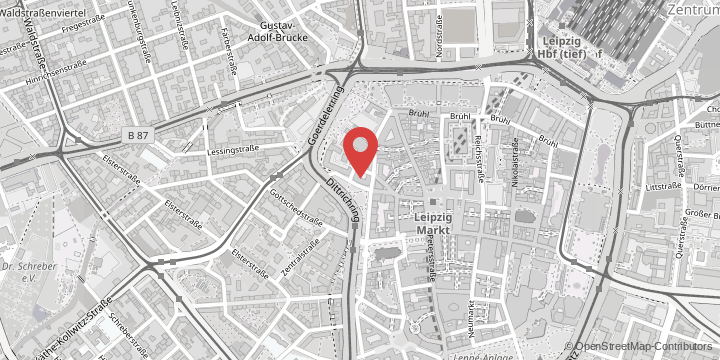

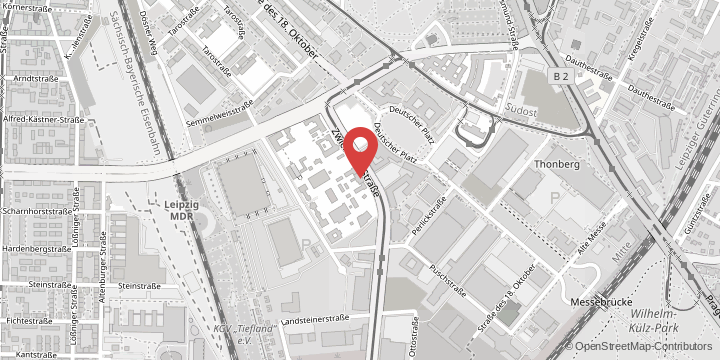

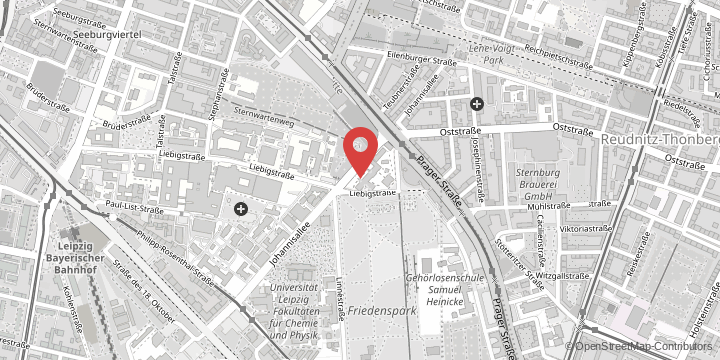

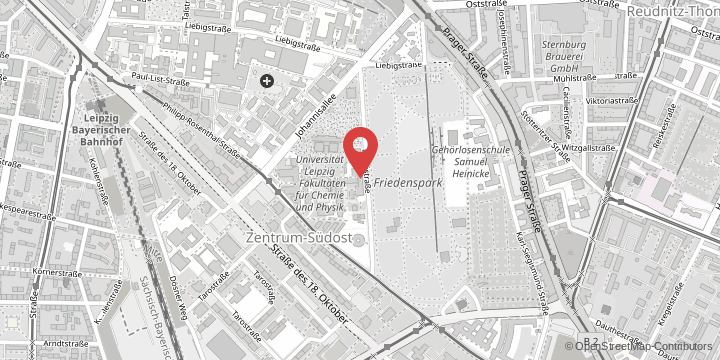

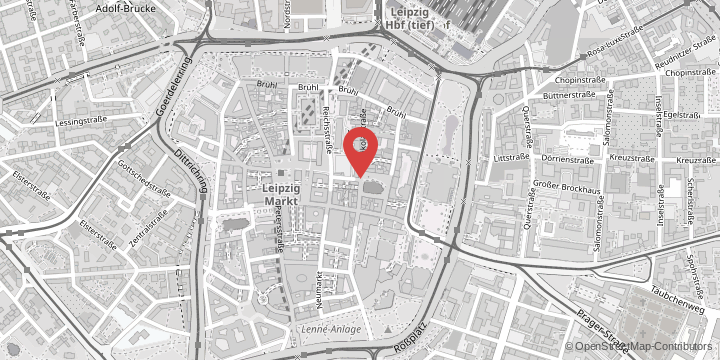

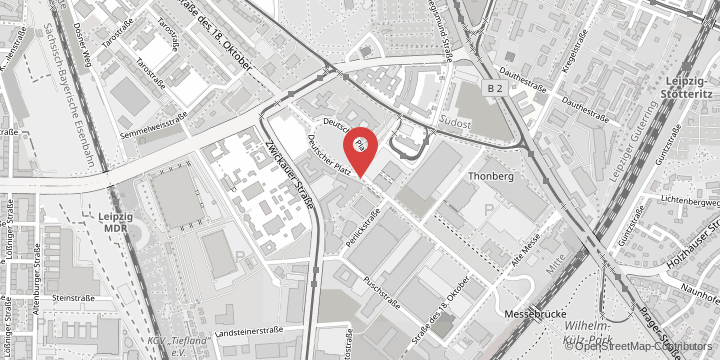

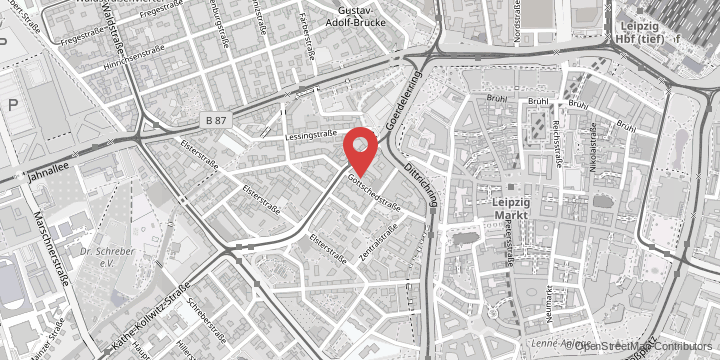

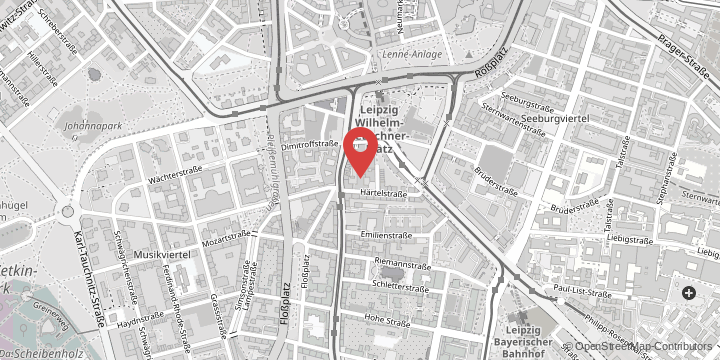

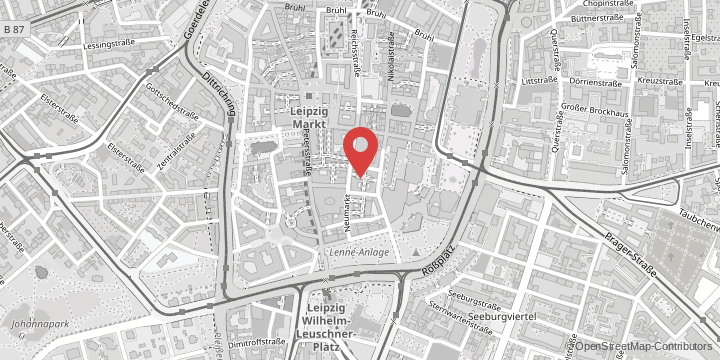

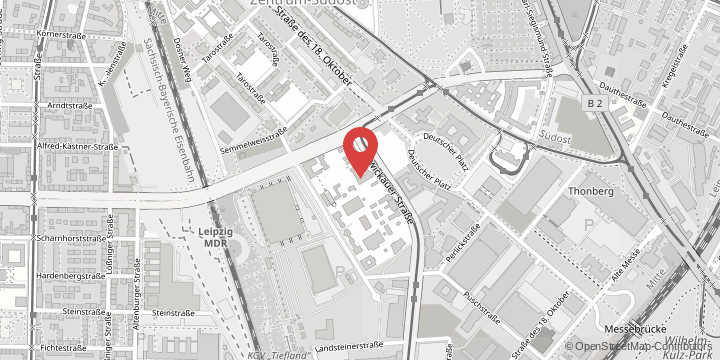

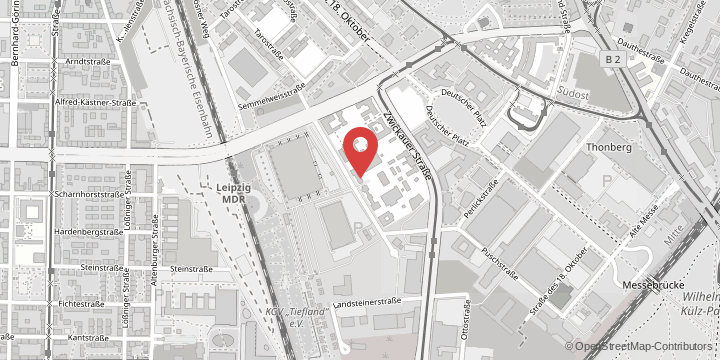

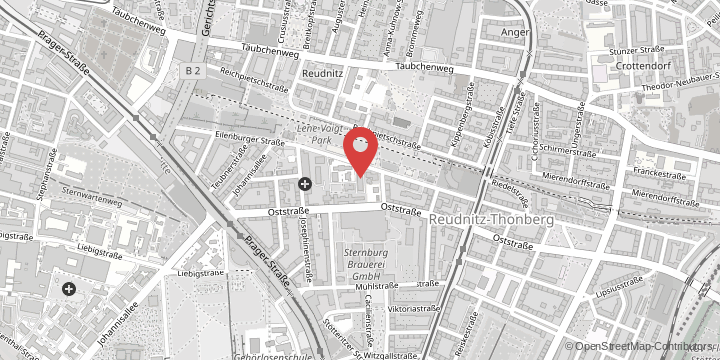

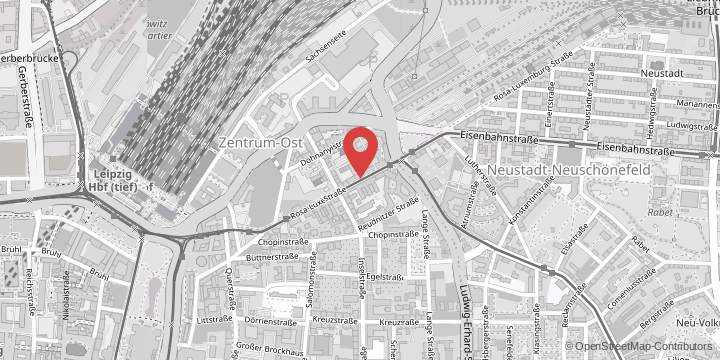

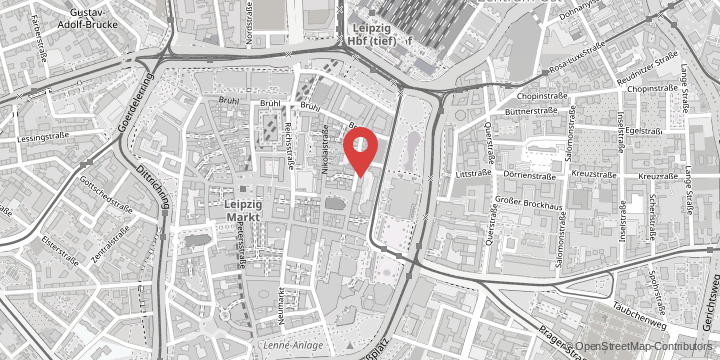

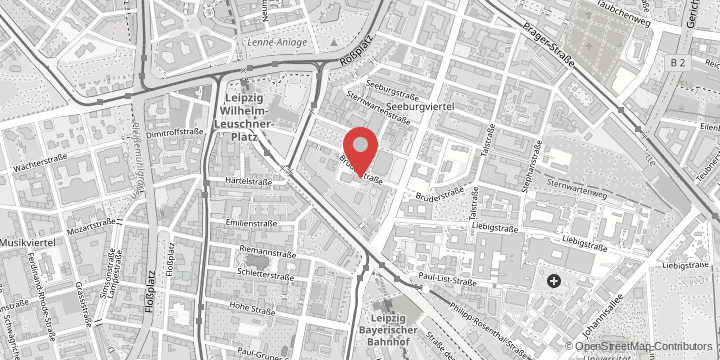

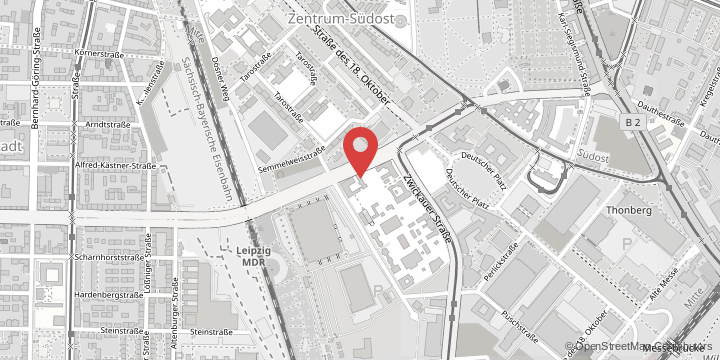

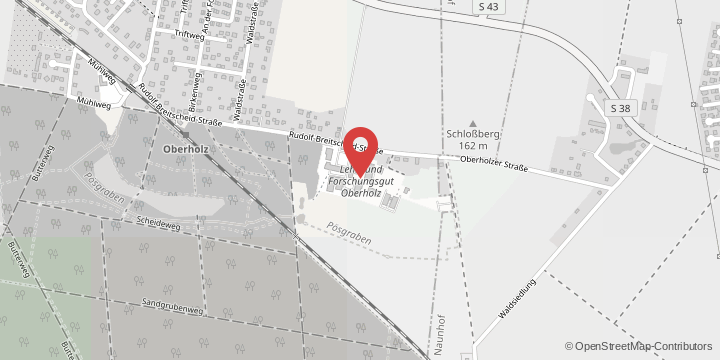

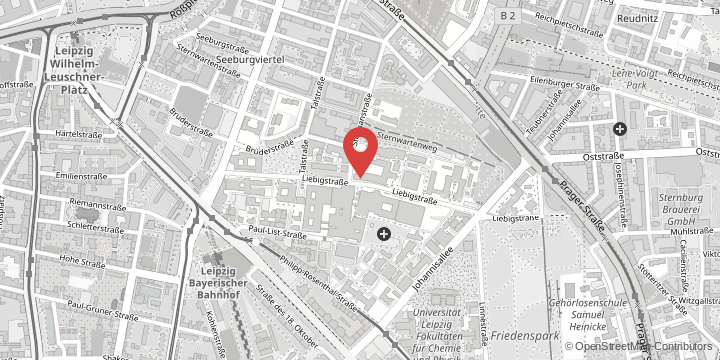

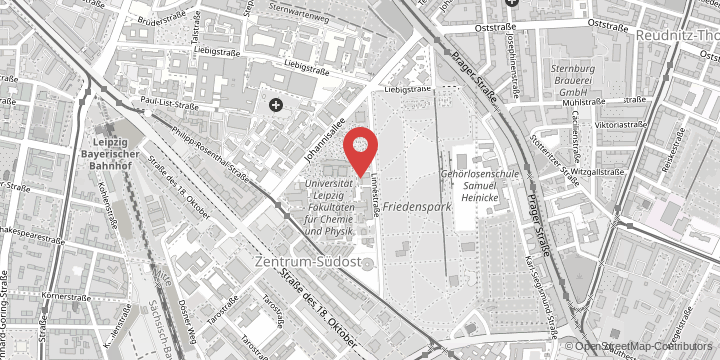

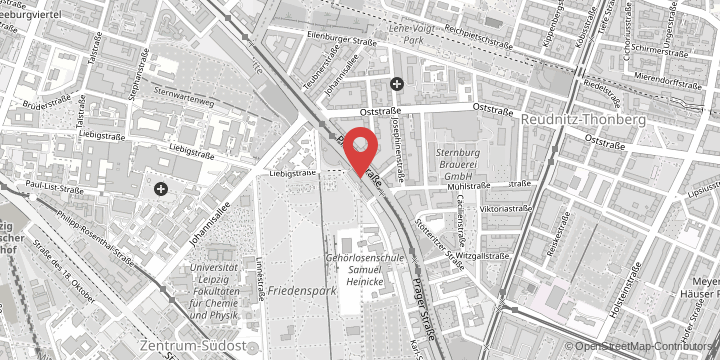

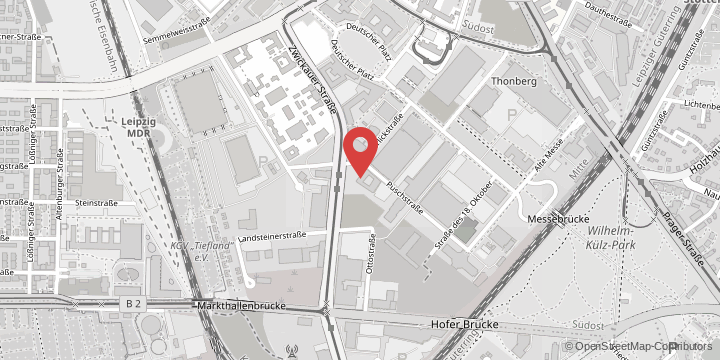

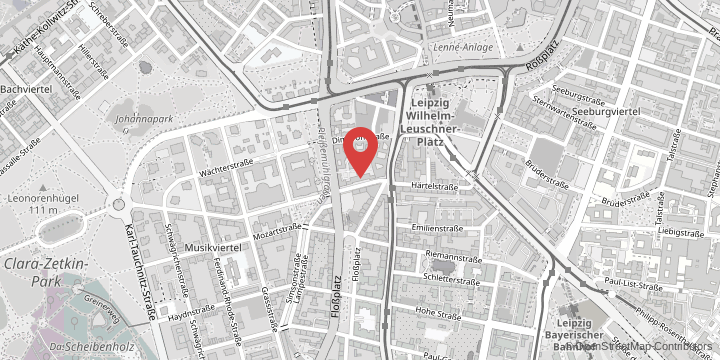

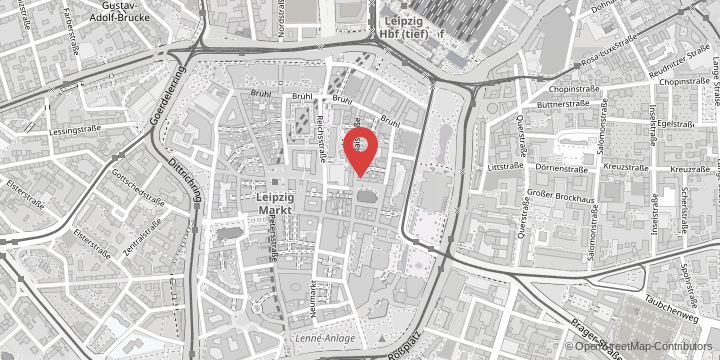

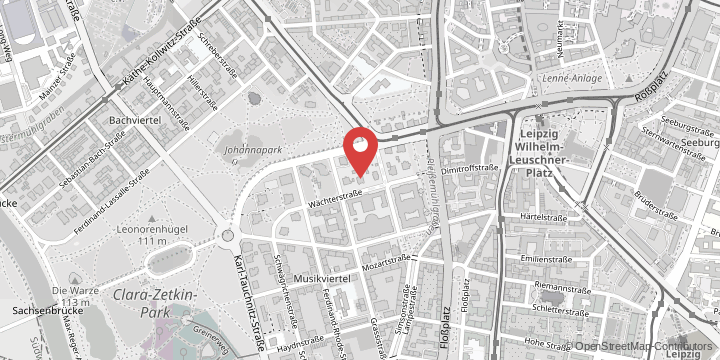

On 14 December 2021 at 6.15pm, project staff will inform members of the public about the latest work in Heliopolis at a lecture in the lecture hall building at Leipzig University (lecture hall 2, subject to the “2G” rule).