Newly elected anti-Semitism commissioner

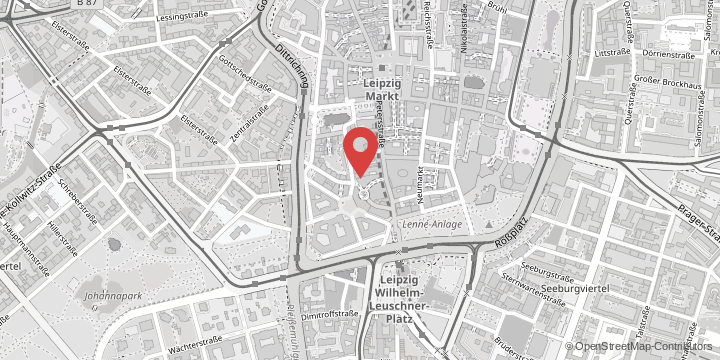

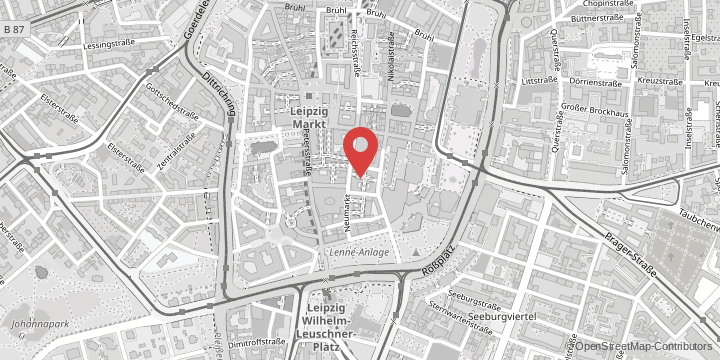

Professor Gert Pickel was elected anti-Semitism commissioner for Leipzig University on 23 January 2024. The Leipzig University Senate decided in December 2023 to create this position in response to the increase in anti-Semitic incidents and discrimination in Germany as a whole, but also at universities in particular.

“In this role, I primarily want to be a point of contact for Jewish students and staff at Leipzig University,” says Pickel. “At the same time, I want to strengthen and advance the critical and differentiated debate on anti-Semitism at Leipzig University. This seems to me to be an important task for the University, especially in view of the continued existence of anti-Semitism as well as the revival of anti-Semitic resentment that can be seen in the public sphere.”

Interview: Anti-Semitism often disguises itself as something harmless

The Leipzig Authoritarianism Study regularly analyses how widespread anti-Semitic resentment is in Germany. Which population groups stand out and what developments have you observed in recent years?

While traditional and overt anti-Semitism has declined since 2002 and only slightly more than 3% of Germans are hard-core anti-Semites, 30% of Germans have been convinced of the validity of secondary anti-Semitism for decades. Approval rates for anti-Semitism related to Israel also fell slightly between 2020 and 2022, ranging between 10 and 20 per cent. Anti-Semitic resentment has therefore not really increased, it has just become more present in public life – and is more often voiced.

Anti-Semitic resentment is particularly strong on the far right of the political spectrum and up to the centre of society, as well as in parts of Muslim communities. While the former tend to resort to an anti-Semitism motivated by a deflection of guilt (secondary anti-Semitism), which can go as far as a reversal of guilt in which the Jews themselves are ultimately blamed for the Holocaust, anti-Semitism related to Israel is more widespread among Muslims than the general population.

This is shown in the results of the Leipzig Authoritarianism Study and the accompanying survey of Muslims in the Radical Islam versus Radical Anti-Islam (RiRa) project. According to these findings, 52% of German Muslims think that the establishment of the state of Israel was a bad idea. However, it is also true that half of Muslims do not approve of anti-Semitism related to Israel. At the same time, among Germans who identify with the right-wing spectrum, secondary anti-Semitism has risen to over 60%. Not to qualify the findings, but Anti-Semitism is by no means just a Muslim problem, as some would have us believe. Strictly speaking, it must be decided on a case-by-case basis whether a person is critical of Israel or anti-Semitic.

Moreover, anti-Semitic resentment is less common among younger people in Germany than among older people, which is particularly true of secondary anti-Semitism.

In what forms do we encounter anti-Semitism in daily life?

Anti-Semitic resentment has never really disappeared in our post-national socialist society. Anti-Semites have only increasingly sought a way of communication that when pressed allows them to deny being anti-Semitic. Saying, for example, that the “cult of remembrance” with the Holocaust can be put to rest today, or that Israel is to blame for all the misery in the world, makes it possible for people to make anti-Semitic statements and then if necessary to declare these to be just harmless expressions of opinion.

The same can be said of anti-Semitism based on demonisation, delegitimisation and double standards, which disguises itself as criticism of Israel but in reality does not express any concrete – and therefore justified – criticism. Behind these statements lies a broader internalisation of anti-Semitic resentment in society than we would like to believe. For example, the Leipzig Authoritarianism Study 2022 found that 41% of Germans agree with the statement that “Reparation claims against Germany often do not benefit the victims at all, but instead a Holocaust industry of resourceful lawyers,” and 19% think that “Israel’s policy in Palestine is just as bad as the Nazis’ policy during the Second World War.” And these are only those who explicitly agree with such statements and don’t simply avoid answering.

On the other hand, it seems that Germans show more solidarity with Israel than people in other European countries do – for example, with regard to the Hamas terrorist attacks on 7 October. In your opinion, is this really the case, and if so is it linked to Germany’s Nazi past?

There is no question that this strong solidarity here can also be explained by Germany’s heavily burdened past. This has led to special relations with Israel, not only on a political level, but also through personal visits by Germans to Israel and an increased focus on Nazi crimes.

At the same time, there have always been countermovements, as I have already pointed out in the case of secondary anti-Semitism, with its attempt to distance itself from the Nazi past. Despite the growing openness, anti-Semitic resentment remains deeply rooted and appears when people are looking for scapegoats. In this respect, we can probably agree with the psychoanalyst Zvi Rex: “The Germans will never forgive the Jews for Auschwitz.”