“It was the best thing that could have happened to us”

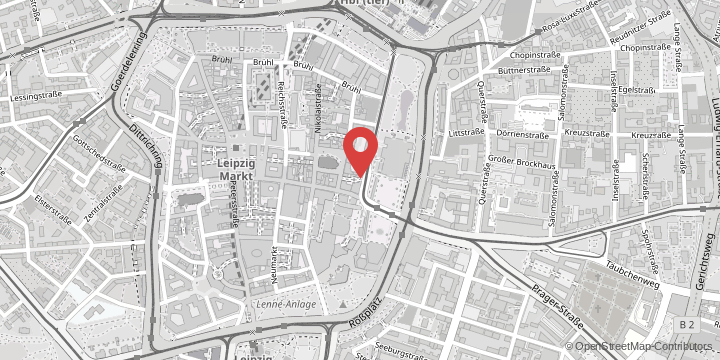

The idea of doing a doctorate has been with Natalka Sniadanko since her first degree in Ukrainian studies in Lviv, which she completed in 1995. Two things occurred that were to have a profound effect on her life, albeit not immediately. “We were the first Ukrainian studies class after the fall of communism. The old books were no longer relevant, but there were no new ones yet,” she recalls, adding that many university professors didn’t know what to do with their students. “The university hired the well-known poet Viktor Neborak as a visiting lecturer for a few semesters,” says Sniadanko. “He introduced us to contemporary Ukrainian poetry and also prose that had not made it to publishers but was being traded under the counter. It was the best thing that could have happened to us. I saw not only exciting works of literature, but also how well you can combine literary writing and literary studies.” She first went to Germany, where she studied Polish and Romance studies at the Albert Ludwig University of Freiburg.

New angles on a familiar favourite

Back in Lviv in 1997, she began translating literary works and specialised in this field during her postgraduate studies at the University of Warsaw. “I think it was at that time that the literary scholar Tamara Hundorova wrote a book about Olha Kobylianska – one of the most famous Ukrainian women writers,” says Sniadanko. Hardly anyone in Germany knows her, even though she also wrote in German. “The new analysis lifted her out of the Soviet literary canon, where she merely had a place as a writer interested in the Ukrainian peasantry – and cast her in a completely different light,” she says. It looked at her work through the lens of the various literary theories of the 20th century. “I read it several times because I was so fascinated by it,” Sniadanko explains.

Ukrainian literature is European literature

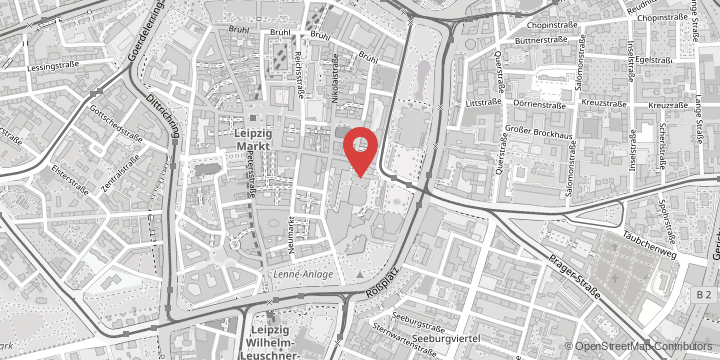

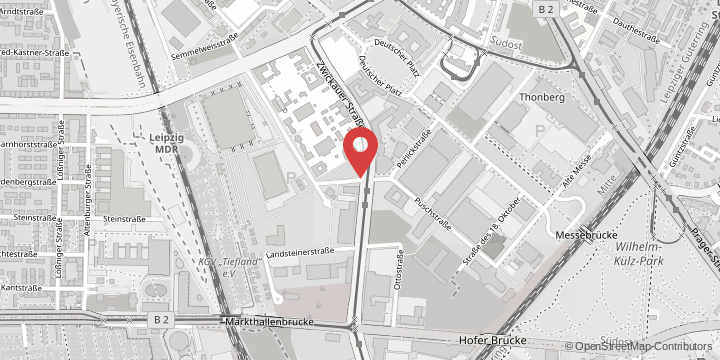

Not surprisingly, Natalka Sniadanko’s doctorate will be on Olha Kobylianska. In her dissertation, she will compare Kobylianska with her favourite German writer – the novelist Eugenie Marlitt, who was widely read in the 19th century. “For example, I am curious about the ideological views expressed in their works,” says Sniadanko.

One thing is particularly important to her: “I want to show that Ukrainian literature actually developed in the European space, alongside the trends we know from other countries – that is, before it was silenced by the Soviet period.” Furthermore, Sniadanko adds, there are relatively few publications on the feminist perspective on works by Ukrainian women.

Sniadanko’s own literature

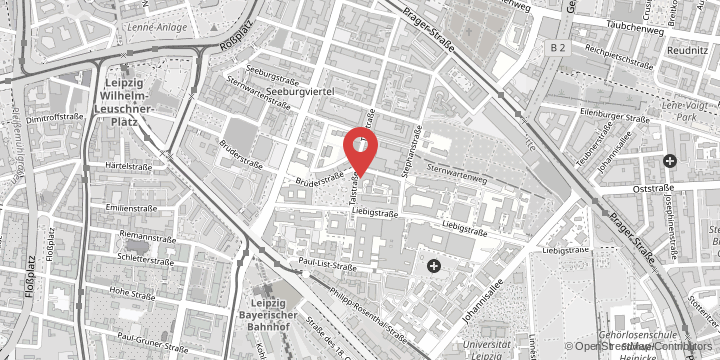

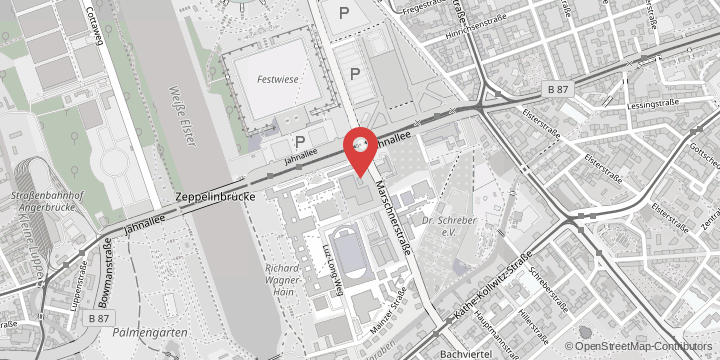

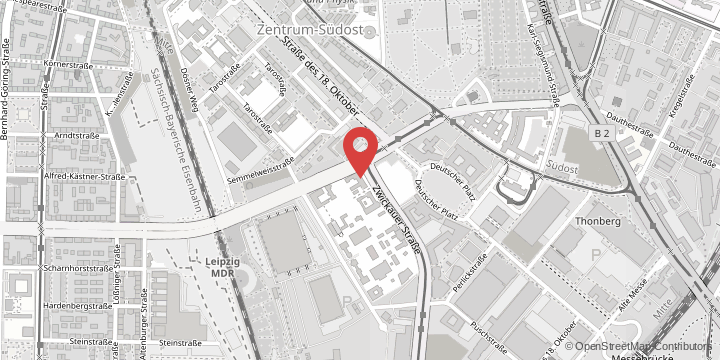

She has been publishing her own literary works since 2001. In the same year, she was awarded a Gaude Polonia scholarship in Warsaw. Further scholarships followed in Austria, Germany, Hungary and Poland. At the same time, she continued to translate, first writing for Ukrainian newspapers and magazines, and later as a freelance writer for the international press, including Deutsche Welle, the New York Times and the Guardian. She has been a freelance author, journalist and translator since 2010. She has been a member of PEN Ukraine since 2018 and a corresponding member of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts since 2022.

Nine of Natalka Sniadanko’s novels have been published so far in a total of 11 countries. She is a translator of over 80 authors from Polish and German into Ukrainian.

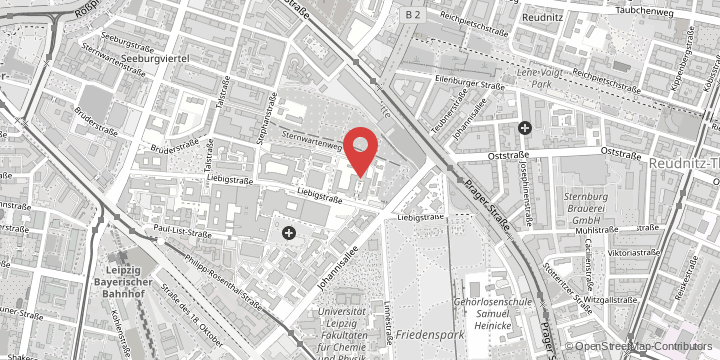

After war broke out in Ukraine, the German Literature Archive in Marbach offered her a scholarship in Germany, which she was happy to accept. “There I was able to find quite a bit about Olha Kobylianska and other Ukrainian writers that was in the papers of other authors,” she says.

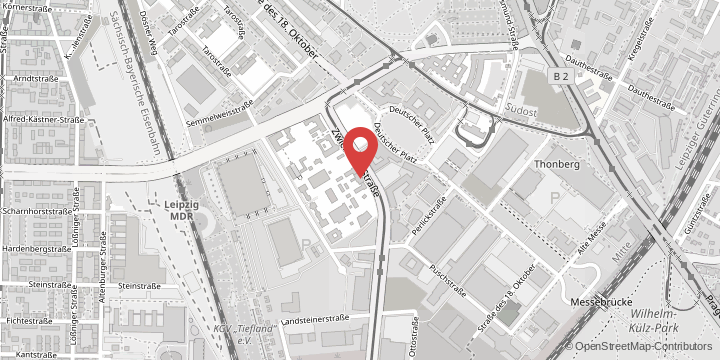

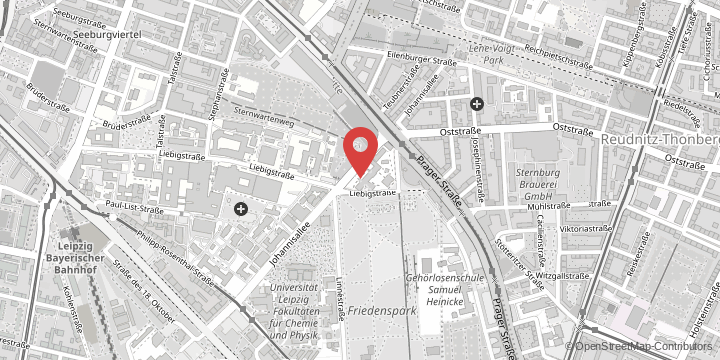

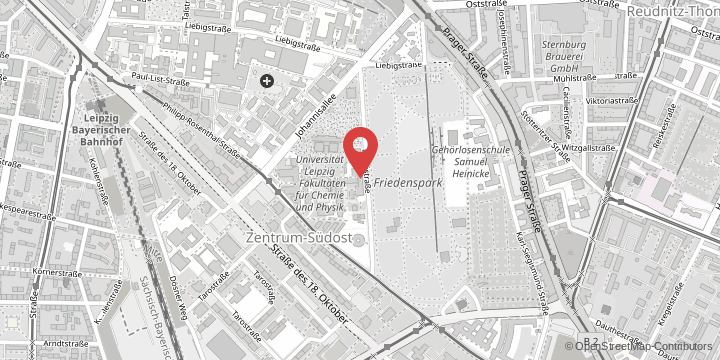

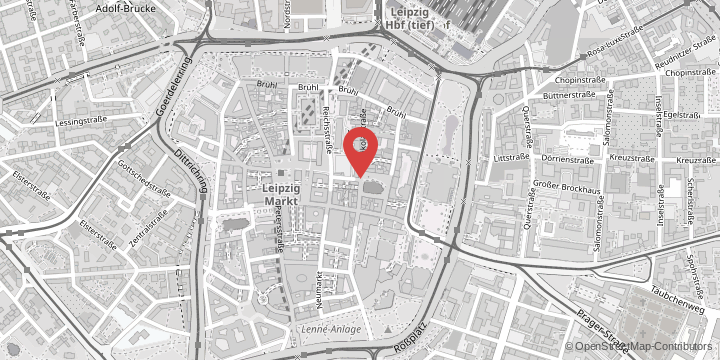

- Professor Anna Artwinska: “Leipzig offers a favourable environment for research projects”

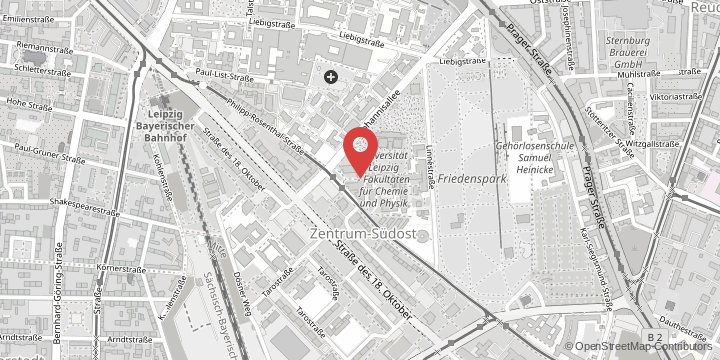

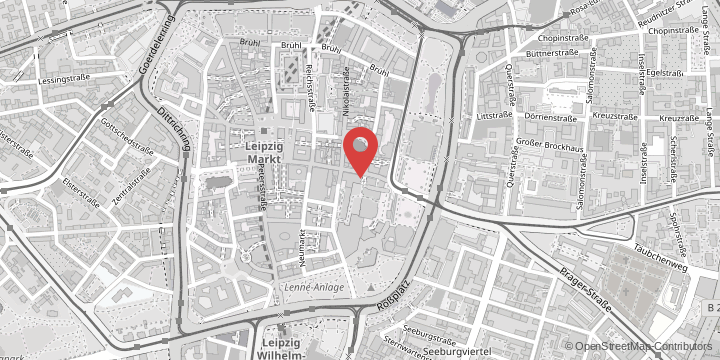

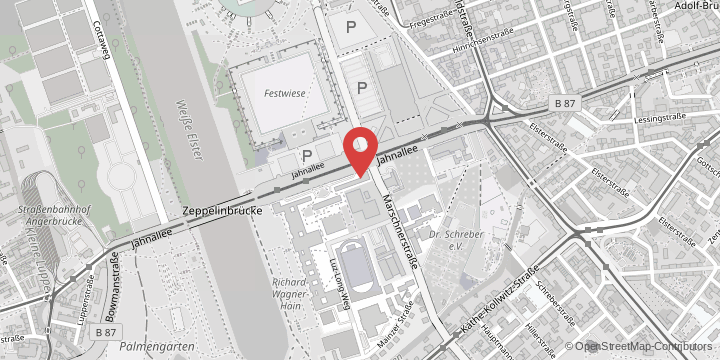

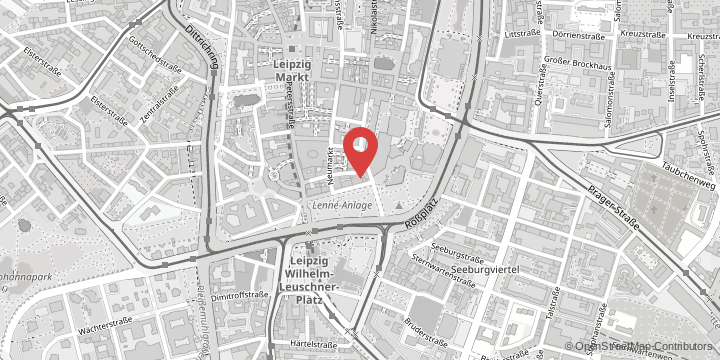

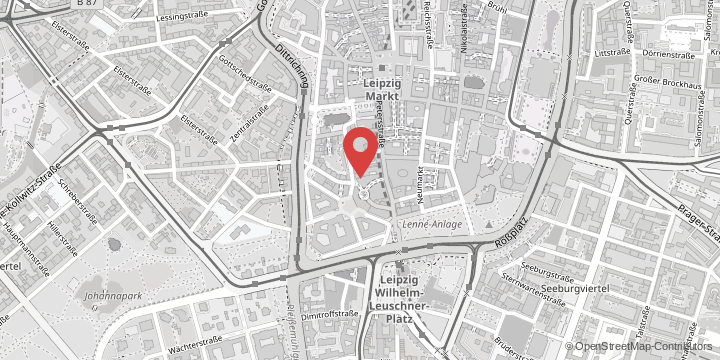

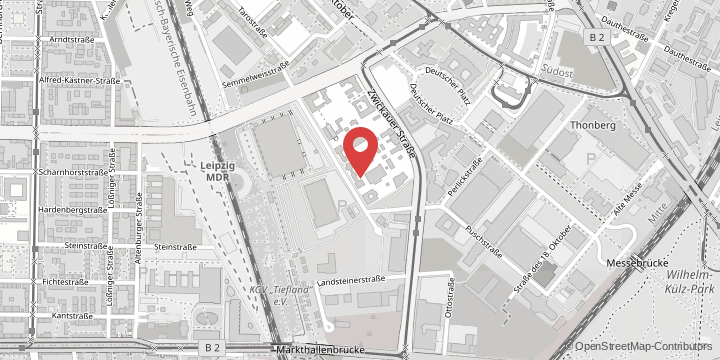

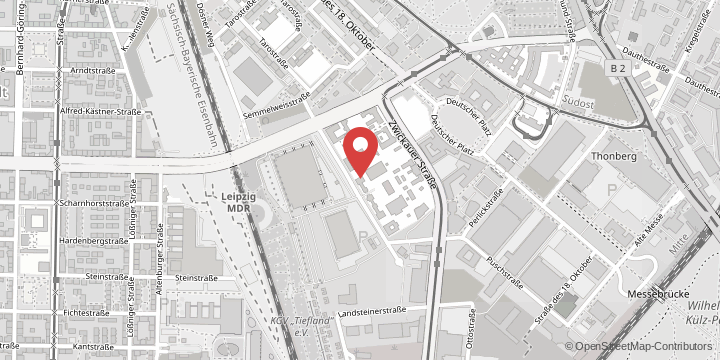

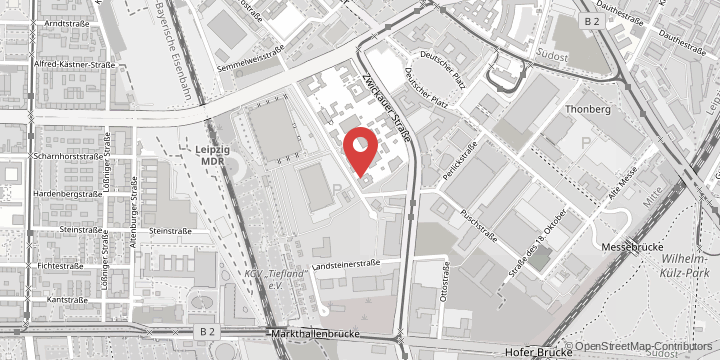

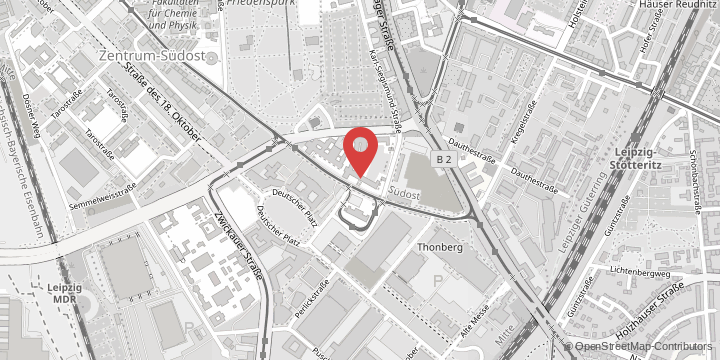

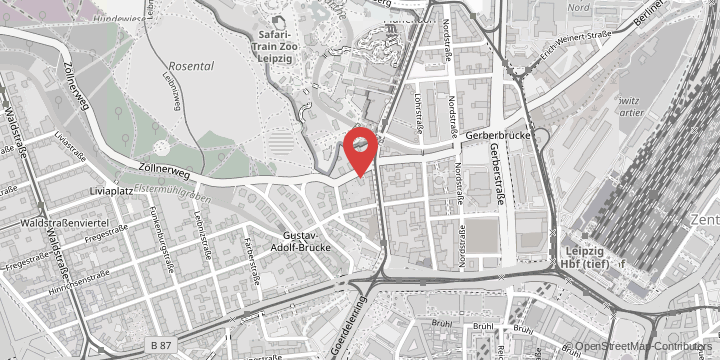

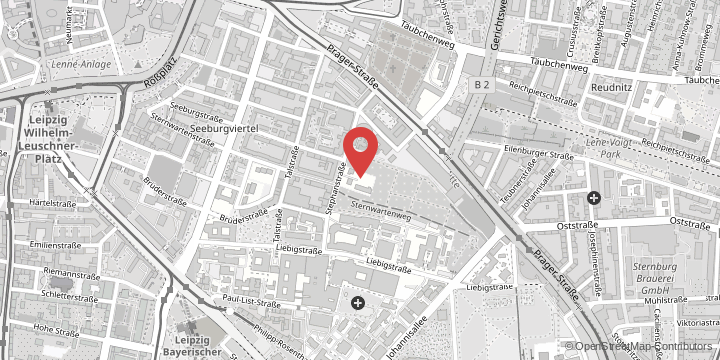

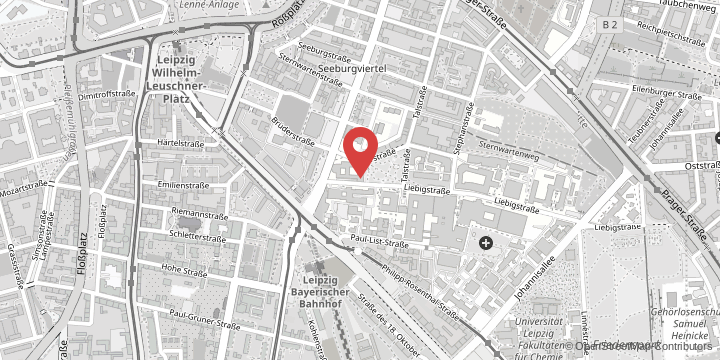

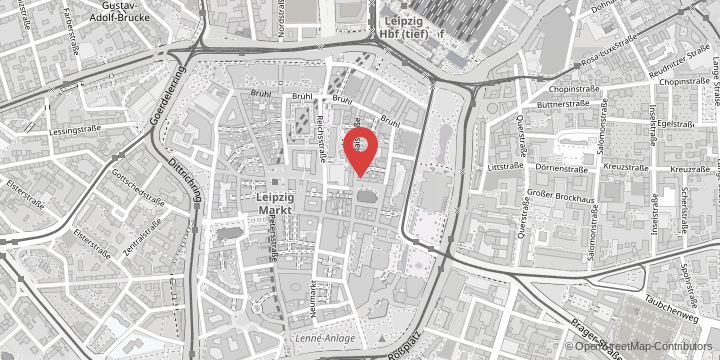

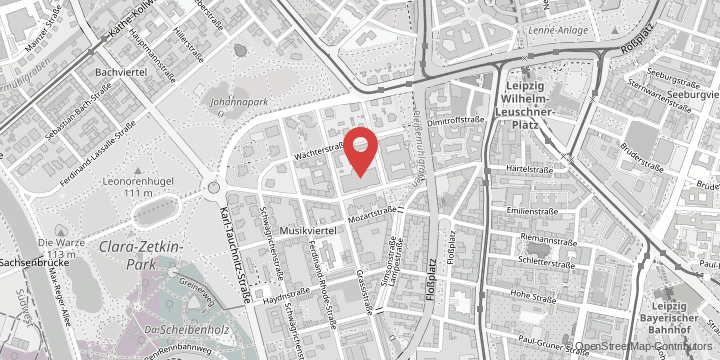

Professor Anna Artwinska from the Institute of Slavonic Studies is delighted that Natalka Sniadanko has now been able to move seamlessly from Marbach to Leipzig to fulfil her long-held wish to do her doctorate here: “I believe that Leipzig offers a favourable environment for such a project. We have the Centre for Gender Studies and the Literature Institute, and there is a tradition here of combining literary studies and creative writing.” She also believes that the dissertation will make an “enormous contribution to showing that Ukrainian literature has a raison d'être outside the Russian and Soviet context,” and that it will be a boost for Ukrainian Studies in Leipzig. She also likes the fact that Natalka Sniadanko has chosen an author from the modern period and will read her work comparatively.

International recognition

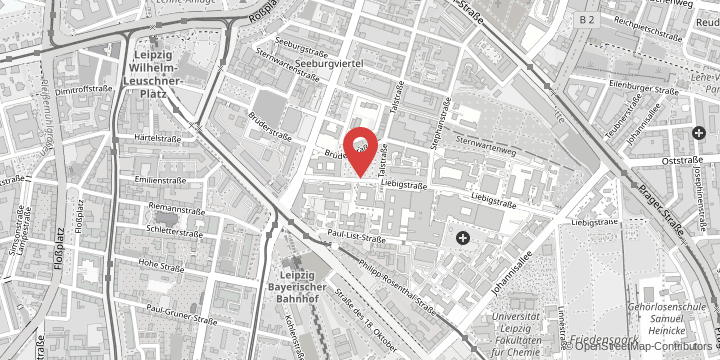

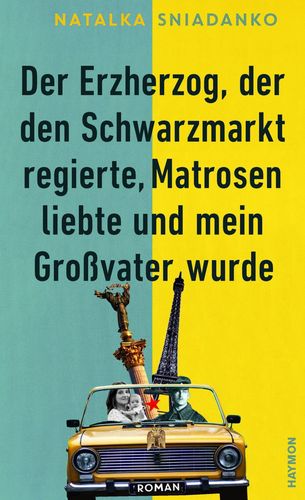

Natalka Sniadanko’s work has already been honoured on numerous occasions. Most recently, her novel Перше слідство імператриці, which has been published under the German title Der Erzherzog, der den Schwarzmarkt regierte, Matrosen liebte und mein Großvater wurde, was nominated for the Angelus Central European Literature Award. Funded by the city of Wroclaw and the daily newspaper Rzeczpospolita, the award is given to the best book of the year published in Poland. The novel was published in Ukraine in 2017, in Austria in 2021 and in Poland in 2022.

According to Sniadanko, the historical background of the book is historically proven, but the family history is fiction. It revolves around the historical figure of Wilhelm of Austria. “He fought for an independent Ukraine, although not without his own interests at heart. He was an idealist and a dreamer who initially had a lot of support and was very popular in the 1920s. But he ended up penniless and actually stateless in a Kyiv prison.” His death was shrouded in legend. “In my book, however, he survives and starts a family that survives many things.”