Professor Rohdewald, almost a year and a half has passed since you said in an interview that a balance of power between the warring parties would be conducive to peace, but that Russia and Ukraine were still far from reaching agreement. How would you assess the situation today?

Professor Stefan Rohdewald: Indeed, as long as Russia continues to attack new territory (Kharkiv) and does not vacate the territories it has occupied, it is unlikely that any agreement will be reached in the near future. In any case, Ukraine has so far demonstrated that it can mobilise an extraordinarily strong and sustained resistance to the all-out attack on its very existence, which means that with continued and of course greater support, the state’s survival is not in question. The goal of incorporating the whole of Ukraine into Russia, which Russia continues to pursue, has been made impossible at great cost. Russia has made it clear that a peace deal is not currently in its interests, as it continues to attack all regions of Ukraine with rocket attacks virtually every night – something that is hardly reported on any more. This has led to a state of trench warfare that could last for years – unless a significant breakthrough, hopefully by the Ukrainian forces, sets everything in motion again.

Instead of peace in the near future, the three Baltic states see Russia as a serious threat and fear they will be next if Russia wins the war against Ukraine. What explanation does history have for this fear?

With the pact between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany in 1939, which marked the beginning of the Second World War, the Baltic states were occupied and large parts of the population were deported or mobilised to serve in the army – a scenario that was completely contrary to international law and is currently affecting Ukraine. After the war, the United Nations (UN), the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), also on the initiative of the Soviet Union, made the renunciation of the use of war and the inviolability of state borders the core of the global and European peace order. Russia’s actions in Georgia, starting in 2008, and in Ukraine, starting in 2014 and escalating significantly in 2022, are aimed at abolishing these principles: then the law of the jungle would apply. Smaller neighbouring states of the neo-imperial Russian state would have to fear the worst. NATO would have to respond immediately – not with nuclear means, of course – to any violation of the territorial integrity of these states, including hybrid violations, for example by Wagner troops, otherwise it would very quickly lose credibility and further increase Putin’s room for manoeuvre. This is currently the greatest fear in the Baltic states, but also in Poland and Romania.

The International Day of Peace was established in 1981. How have the conditions for global peace changed over the past 50 years – and how does Russia’s war against Ukraine relate to this?

In 1979 the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan – and in 1981 martial law was imposed in Poland. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union presented itself as peace-loving and saw the promotion of the peace movement and the UN International Day of Peace as a propaganda priority. The world did not become simpler with the end of the Cold War – but Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine is the most radical break with the principles of the post-1945 European peace order since the genocide of Bosnia’s Muslim population by Serbian troops. Russia’s explicit aim is to (re)establish its own imperial sphere of influence in Europe – peace will only be served now and in the long term if this can be prevented.

You have just been to meetings on Ukraine in Warsaw and Vilnius. How does the international academic community view the chances of peace?

Barring a sudden change in the situation, which is always possible – even Putin being overthrown by a committee to save national interests can never be completely ruled out if there are further failures – the most likely scenario now seems to be a Korean or an Israeli one. Even a treaty with Putin would be hard to believe, especially as he has broken all the binding agreements, including the most recent Ukrainian-Russian border treaty of 2003. Only new leadership and a radical change of policy in Moscow could restore the necessary confidence. Korea has an armistice that has so far stabilised the 1953 status quo without a peace agreement. Israel can only feel secure with its own strength and the security support of a few partners: its existence has been under constant threat from neighbouring states for decades, and to this day it faces a particular existential threat from Iran. The talks recently begun in Vilnius on guaranteeing Ukraine’s security by many states, which are in principle based on Israel’s international protection, now need to be fleshed out and made more concrete.

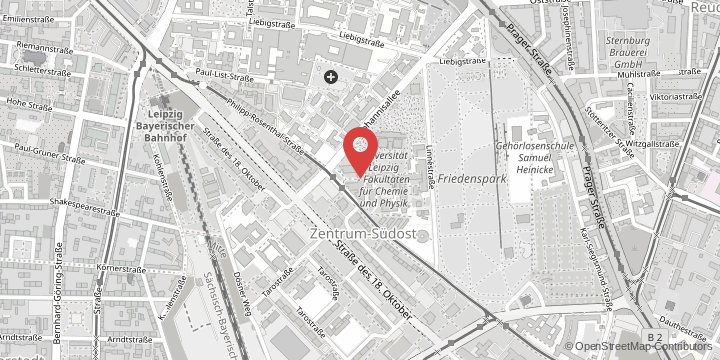

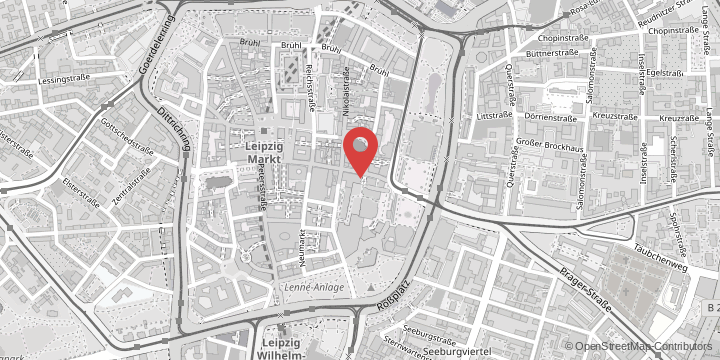

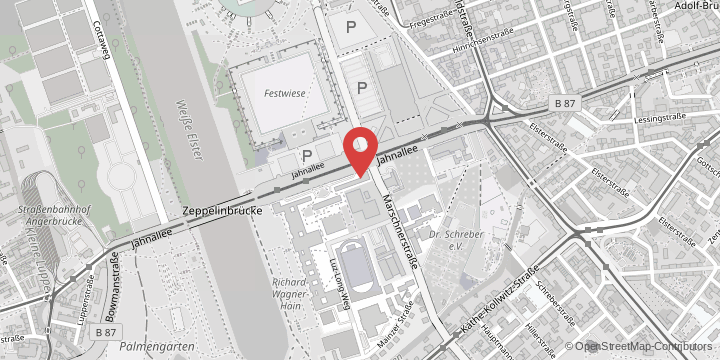

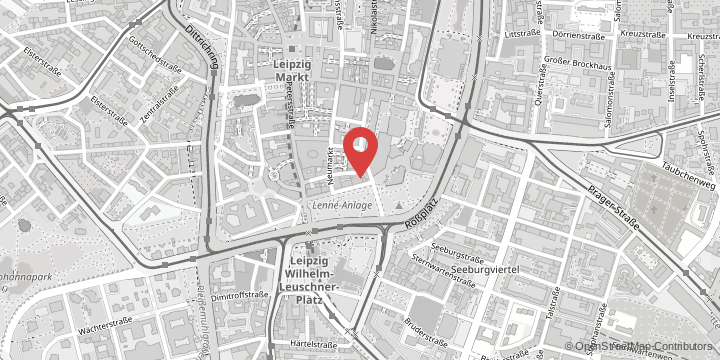

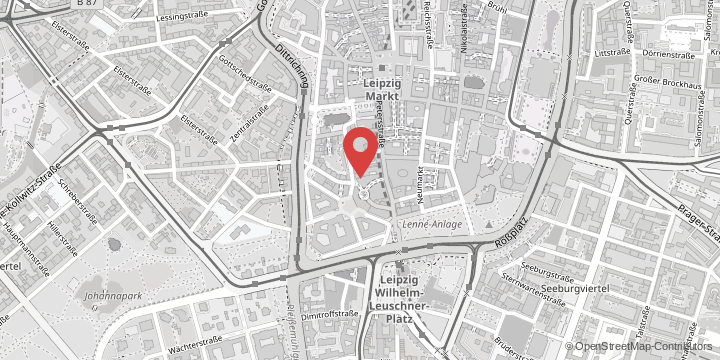

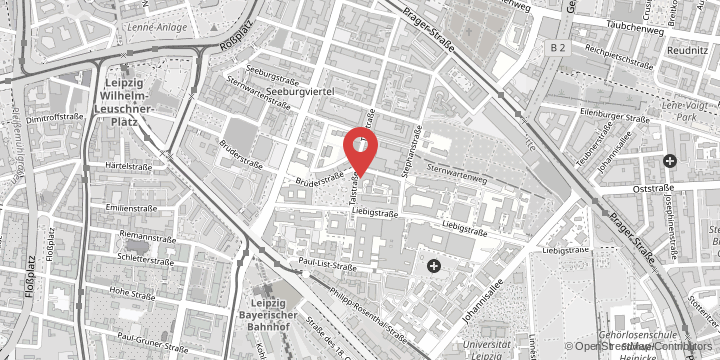

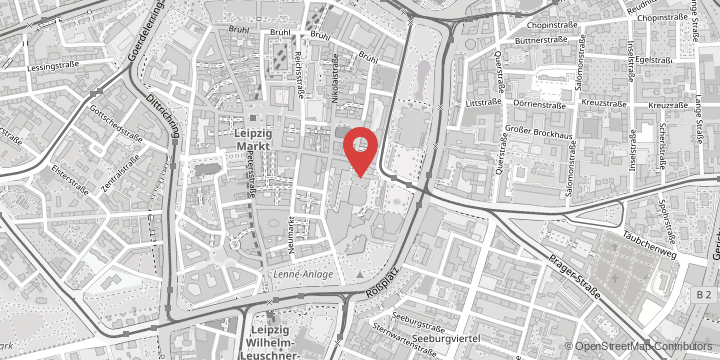

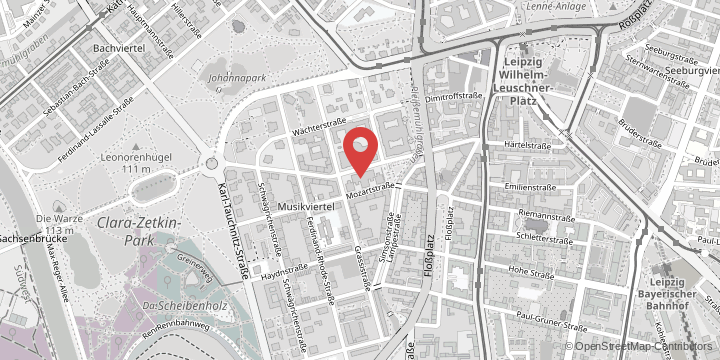

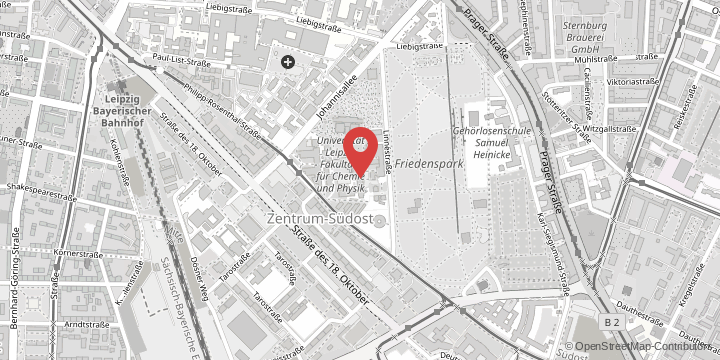

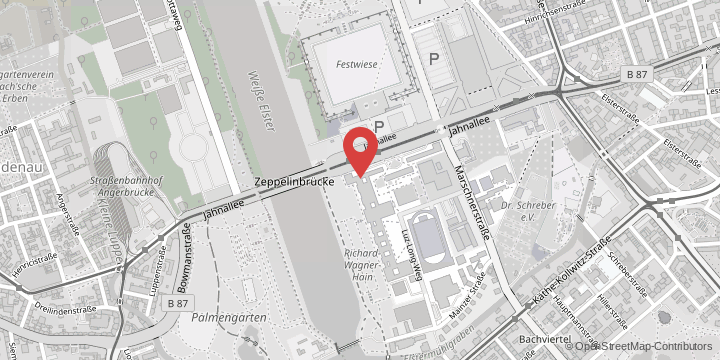

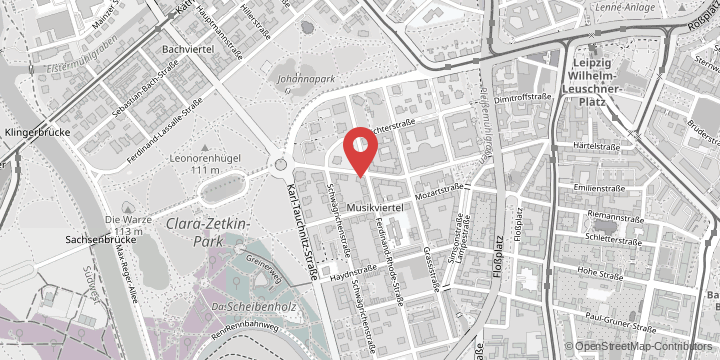

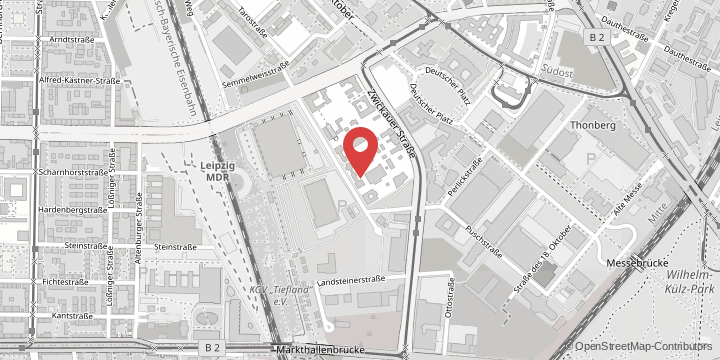

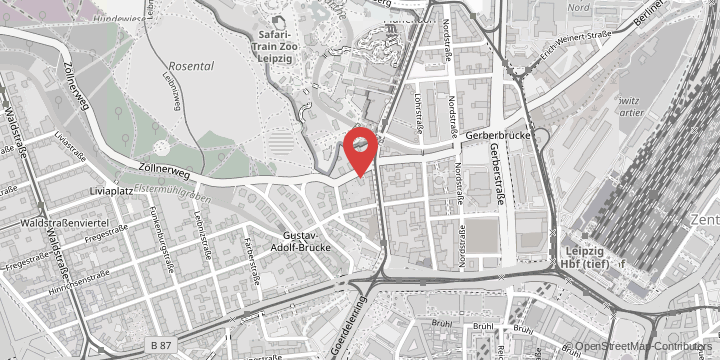

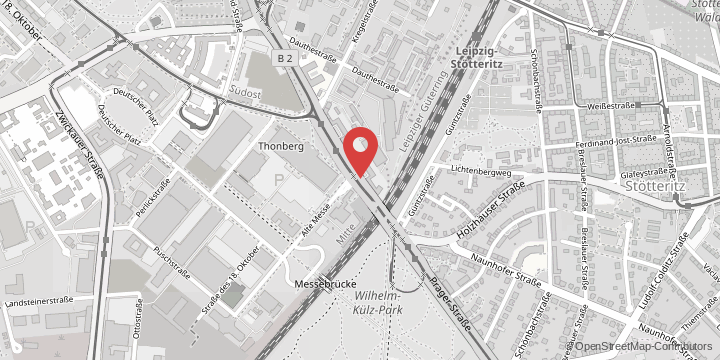

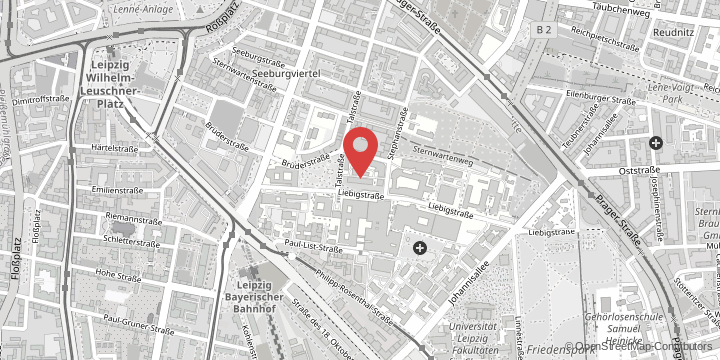

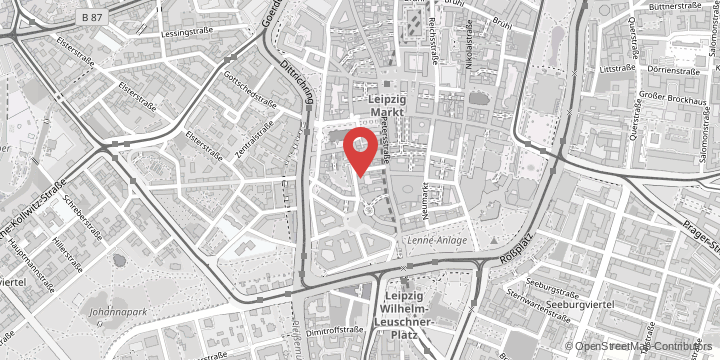

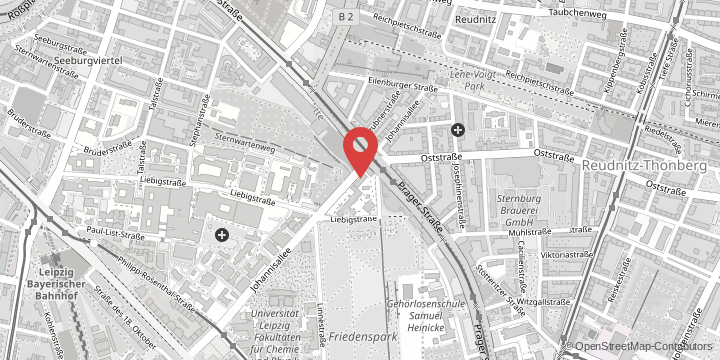

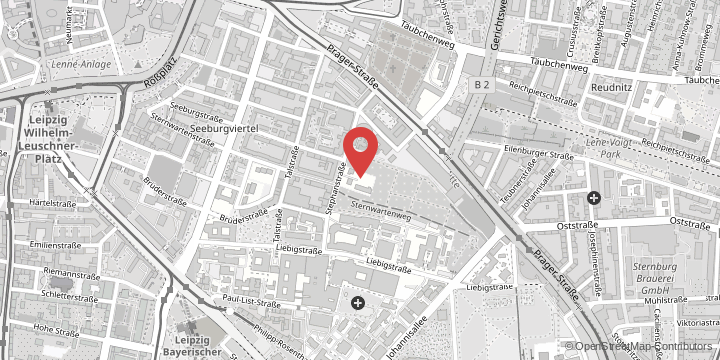

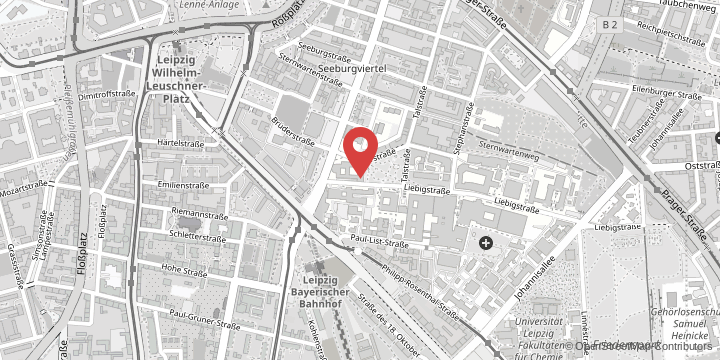

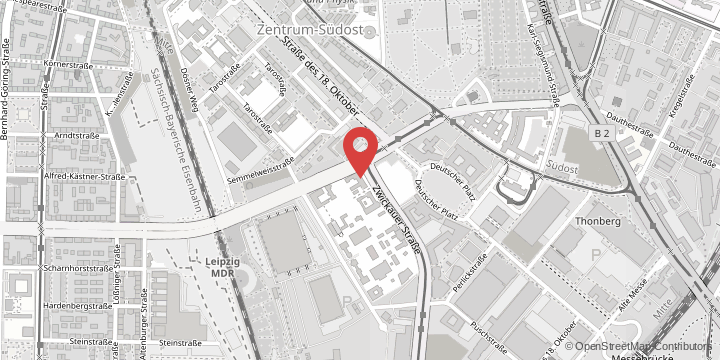

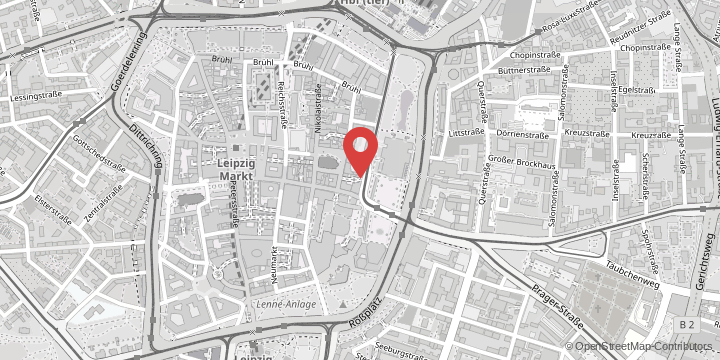

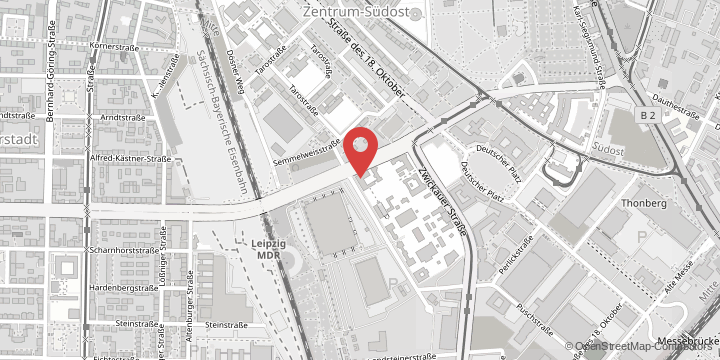

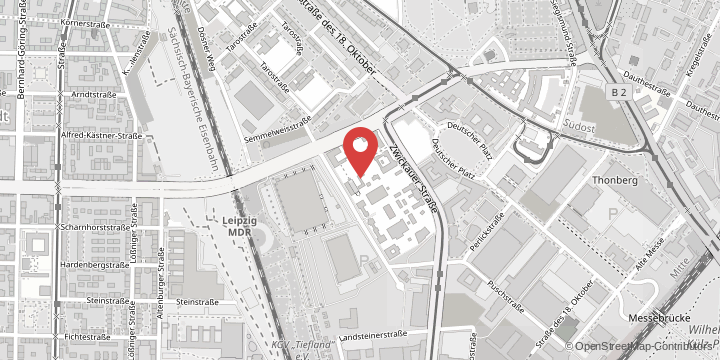

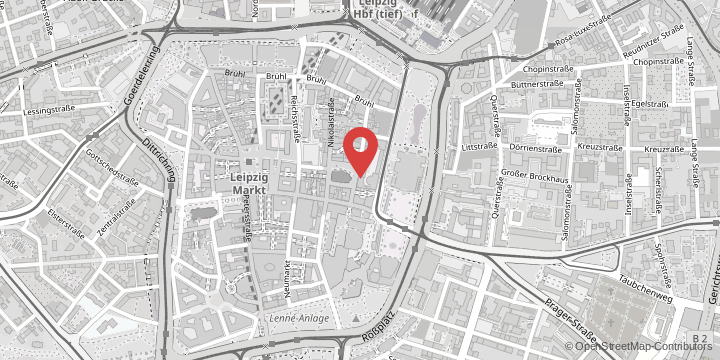

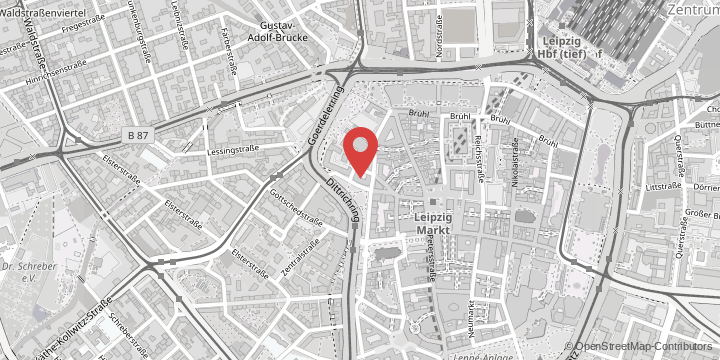

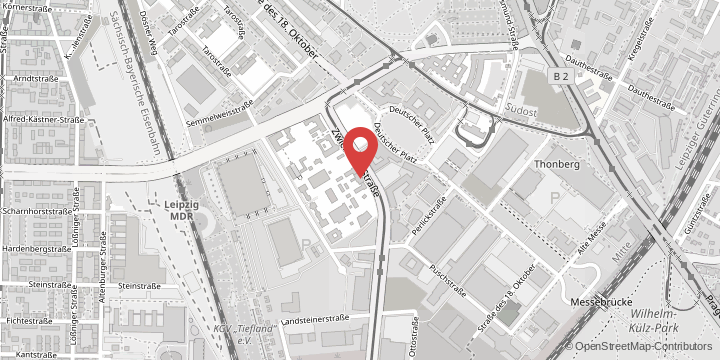

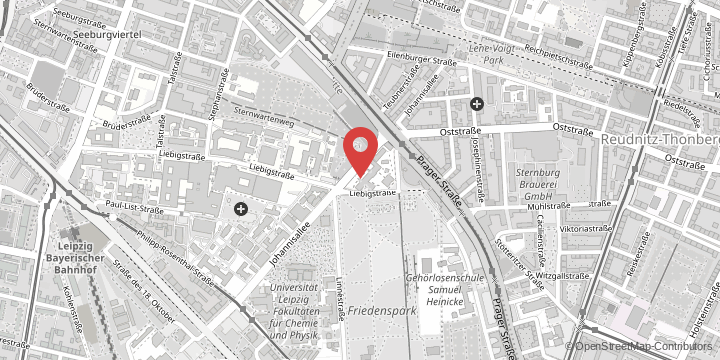

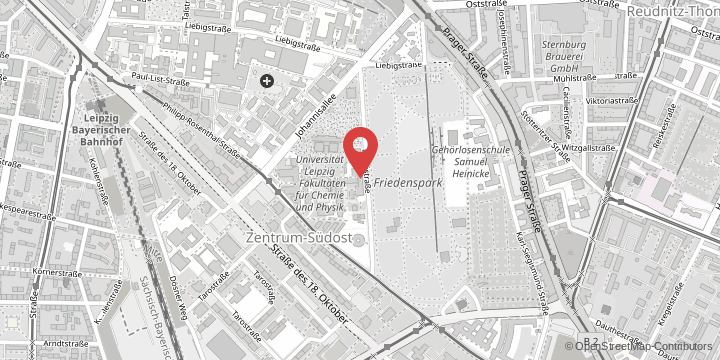

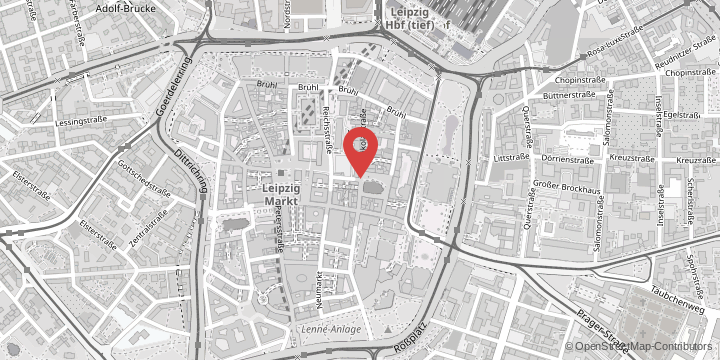

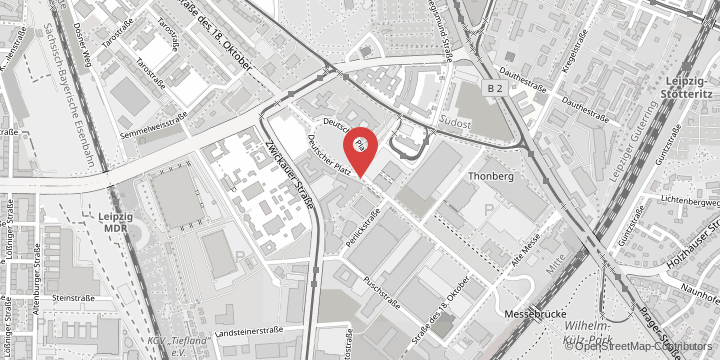

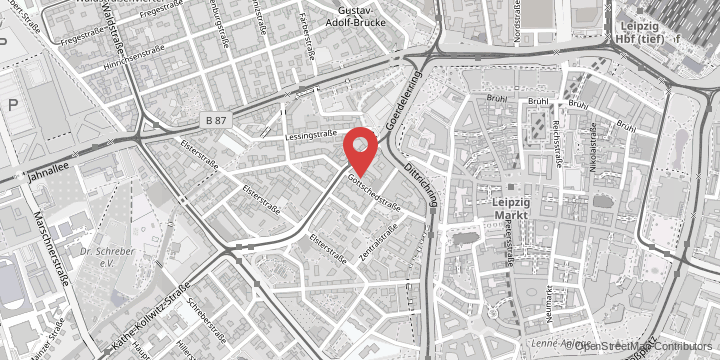

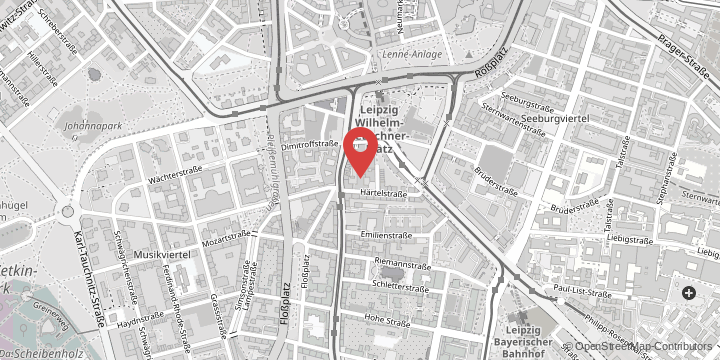

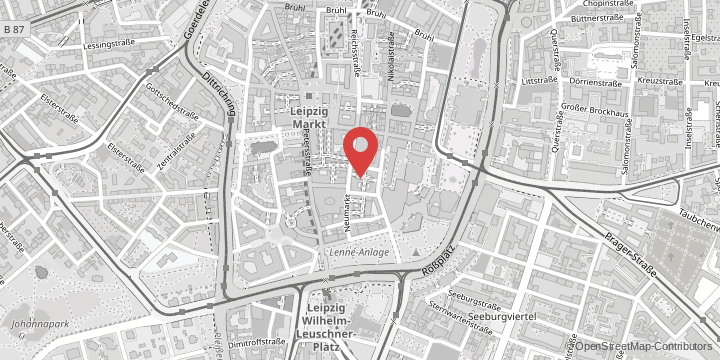

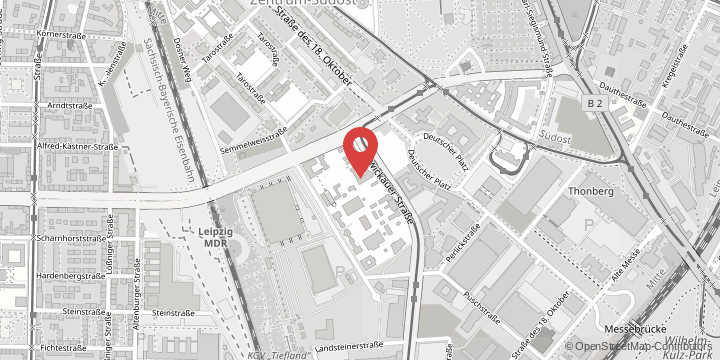

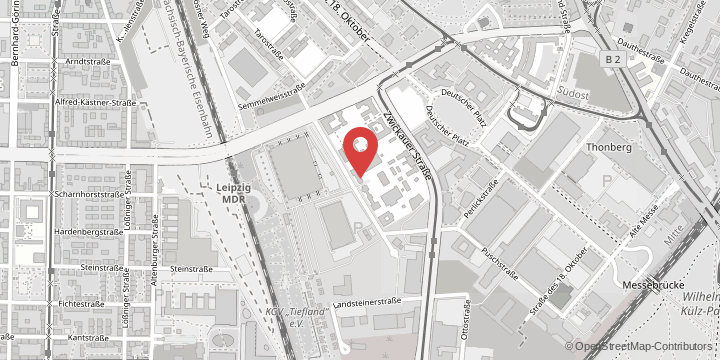

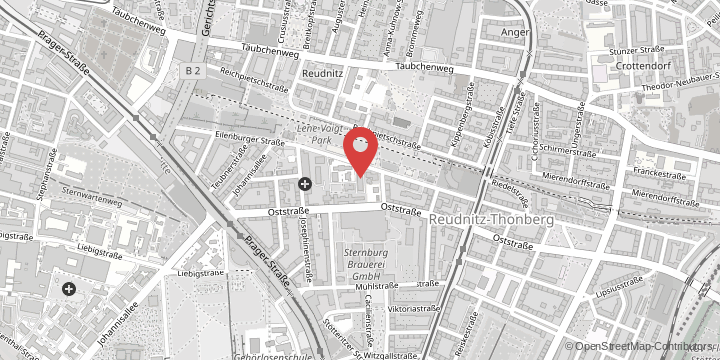

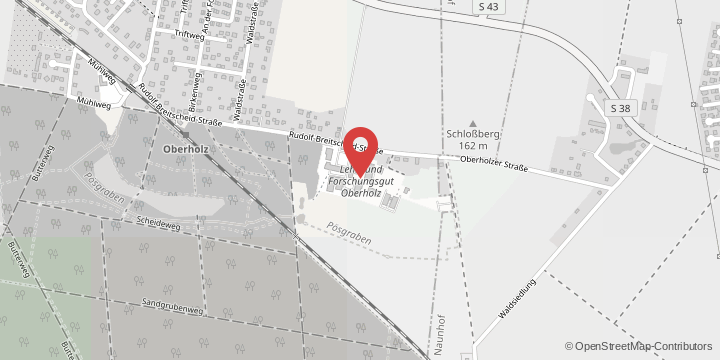

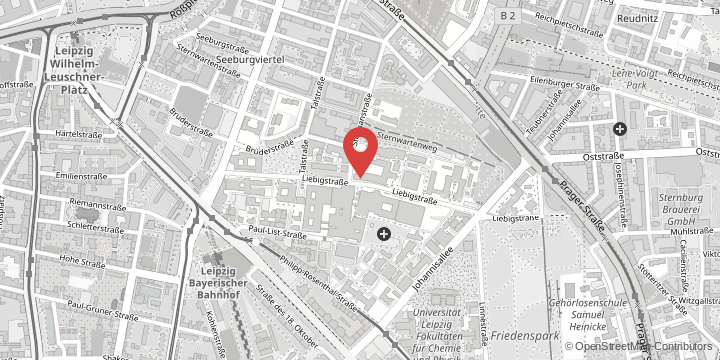

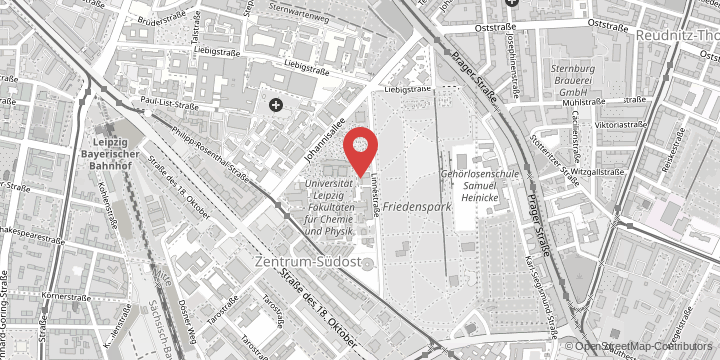

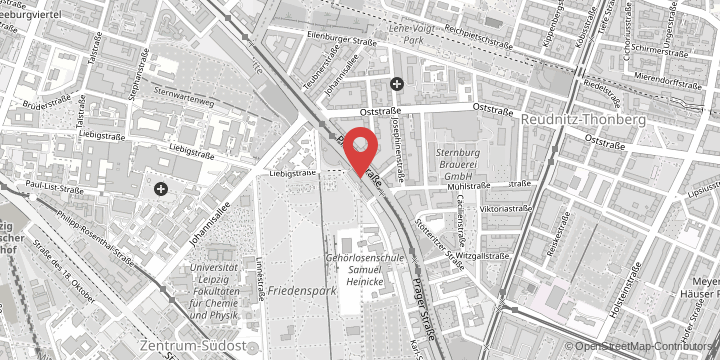

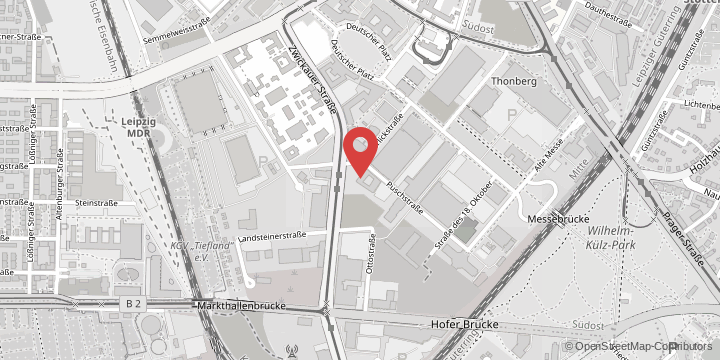

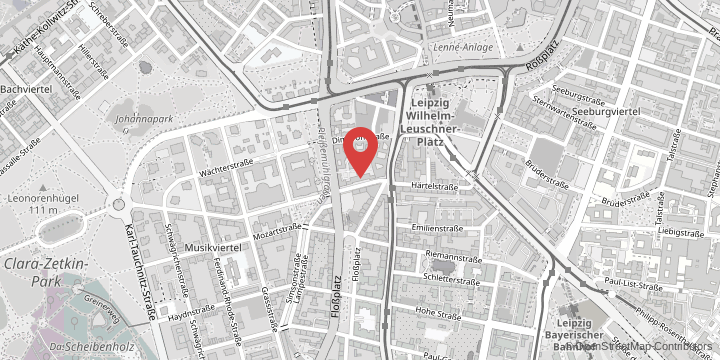

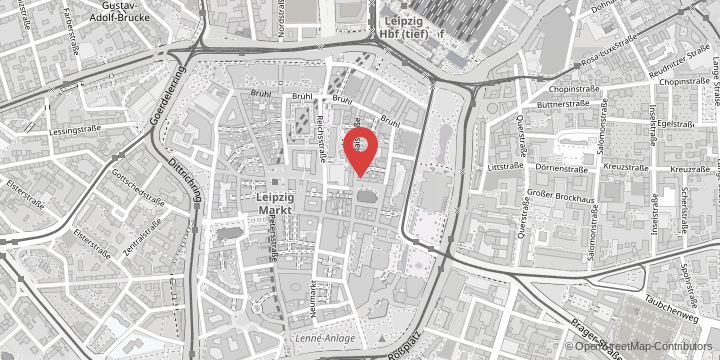

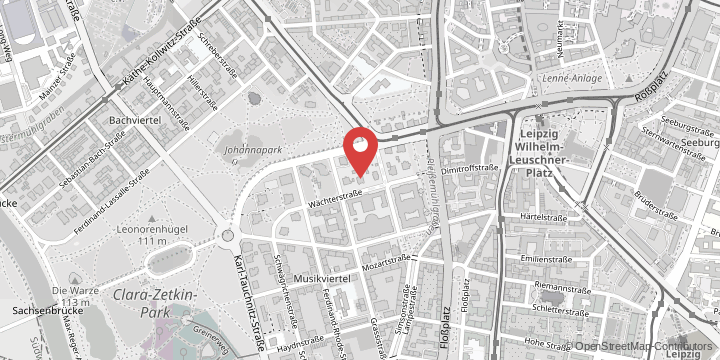

- Professor Stefan Rohdewald has been Professor of Eastern and Southeastern European History at Leipzig University’s Department of History since 2020. The historian is involved in the planned New Global Dynamics Cluster of Excellence as part of the second competition phase of the Excellence Strategy of the German federal and state governments. His research profile focuses on: shared history of Eastern Europe and the Near East; remembrance; urban history; interdependencies between East and West in the history of sport, technology and knowledge; transculturality; and transconfessionality.