Dr Marung, many people think of humanitarian aid as selflessly helping others in need, including reducing or preventing the spread of disease, hunger and water shortages, and helping people to help themselves, regardless of the political context. To what extent has humanitarian aid really been apolitical throughout history?

This is one of the dilemmas of humanitarian aid, as pointed out by scholars including the German historian Johannes Paulmann, which has characterised the history of humanitarian aid since its beginnings in the nineteenth century. Distancing itself from political interests was central to the Red Cross movement – one of the most important originators of the international humanitarian regime. For a long time, the movement’s success rested on this promise to remain apolitical. But at the very moment when the International Committee of the Red Cross was founded in 1863 on the initiative of the Geneva businessman Henri Dunant (in reaction to his experiences on the battlefields of Solferino), the British and French imperial elites were also preparing to defend their colonial projects with humanitarian arguments as part of their “civilising mission”: for example, by trying to improve hygienic conditions in the cities of the colonies. And still other actors – such as European and American missionaries – saw humanitarian aid as their religious duty beyond state interests, but also as a means of winning over believers.

So this tension between the de- and re-politicisation of humanitarian aid is not unique to the Cold War or today’s new global competition. Nevertheless, the professionalisation and expansion of the “Empire of Humanity”, as the American political scientist Michael Barnett critically described it, has gained enormous momentum since the 1970s. During the Cold War, not only did the states of the two blocs try to present themselves as the better half of the world by providing humanitarian aid, but international organisations such as the World Bank – criticised by many as an instrument of American foreign policy – also increasingly turned their attention to humanitarian problems: the World Bank under Robert McNamara, for example, focused on the fight against hunger, while the UN as a whole became the main coordinator of humanitarian aid worldwide. And a variety of non-state actors have taken the stage – sometimes literally, if we think of the Live Aid concerts organised by Bob Geldof. The aim of the first of these concerts in 1985 was to raise money for the starving people of Ethiopia – and it wasn’t long before this enterprise came under fire: as a media spectacle, as “humanitarian business”, but also because Ethiopia was then considered part of the socialist camp, and the Derg regime was seen in the West as authoritarian and repressive.

In Central Europe, many associate humanitarian aid with more or less selfless help from the “first world” for the “third world”, mainly in Africa. Is this view in line with reality?

Donors can also come from the Global South – and this is not a recent development, as we saw with the famous Chinese masks in Europe during the coronavirus pandemic, but again there is a long history here. Cuban doctors, for example, have been an important anchor in short- and long-term health crises in many countries of the Global South since the 1960s, while Cuban medical internationalism has taken on impressive proportions since the Cuban Revolution and was also evident during the coronavirus crisis, when 53 doctors and nurses responded to Italy’s request for help in March 2020.

The recent Russia-Africa Summit in St Petersburg also addressed the issue of grain supplies to Africa, given the war in Ukraine and the expiration of the Russia-Ukraine grain deal. Russia has promised not only to make up for lost supplies from Ukraine, but even to supply grain free of charge. This is just one example of supposedly selfless help. What is behind such generosity?

This is a particularly cynical expression of the dialectic of the de- and re-politicisation of humanitarian aid. It shows how geopolitics can provoke new humanitarian crises and how the struggle for a new world order is being fought on the backs of the most vulnerable groups. We also saw this kind of competition during the coronavirus pandemic, when China, Russia and Western countries intertwined epidemiological, humanitarian, geopolitical, and not least economic interests in their vaccine diplomacy.

In the first half of the twentieth century, for example, China was the main recipient of humanitarian and foreign aid – and from very different directions, with the US and the Soviet Union in particular competing from the 1930s onwards. From the 1960s the Chinese state began to provide humanitarian aid in the Global South, also as a way of distinguishing itself from both the West and the Eastern Bloc, following the Sino-Soviet split in the mid-1960s.

Many people probably share the observation that the world is in multiple crises: not only do we face a multitude of parallel emergencies and challenges, but they are often closely intertwined. These include emergencies caused by the climate crisis, recent and future pandemics, wars in different parts of the world, and natural disasters. This pressing need for cooperation first requires an understanding of the dilemmas of humanitarian aid. Historical classification can help, as can a look at and from different regions of the world.

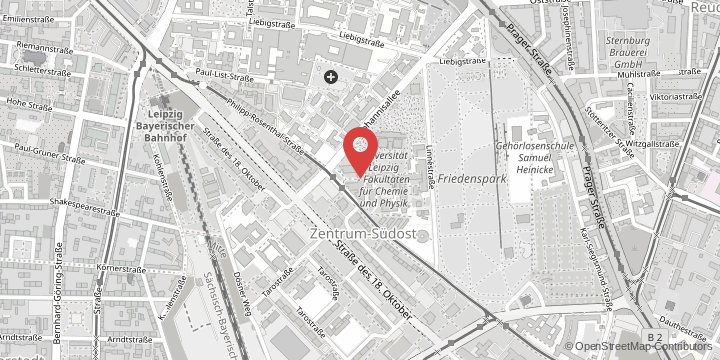

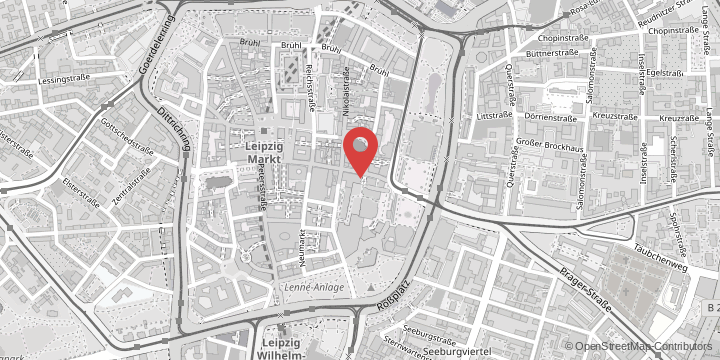

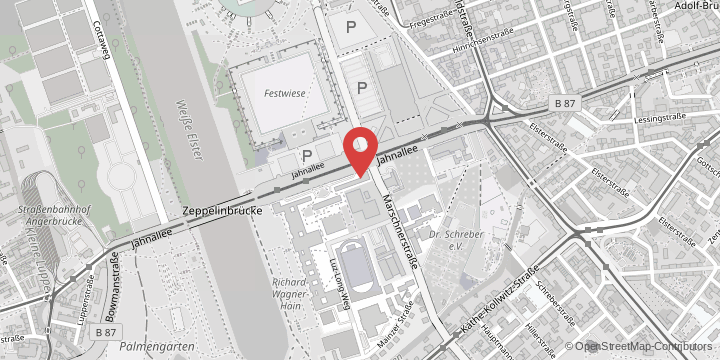

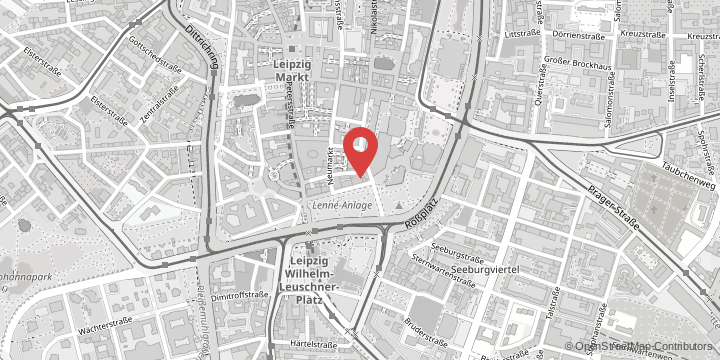

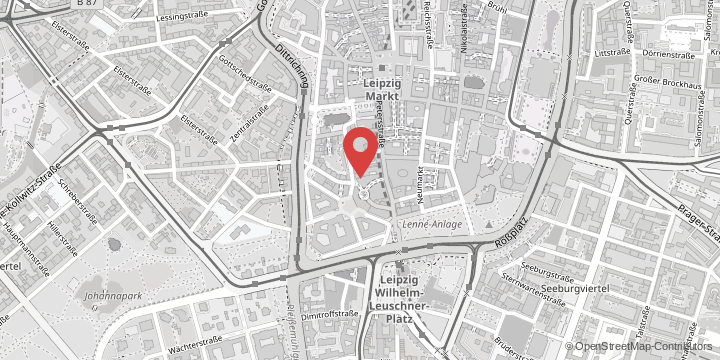

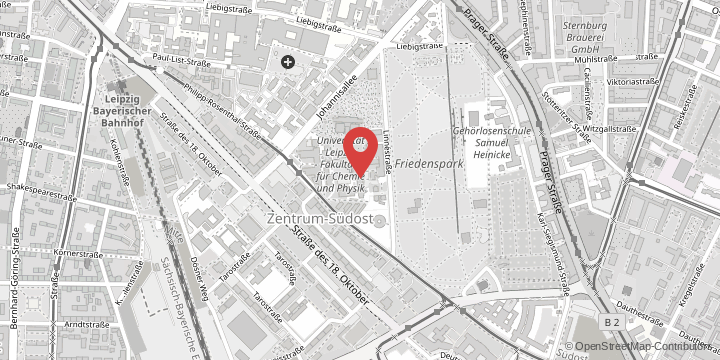

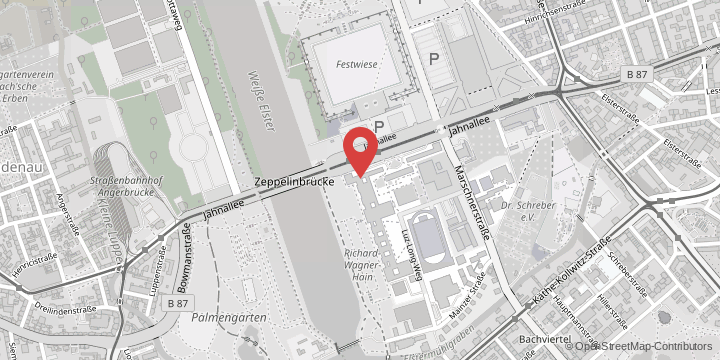

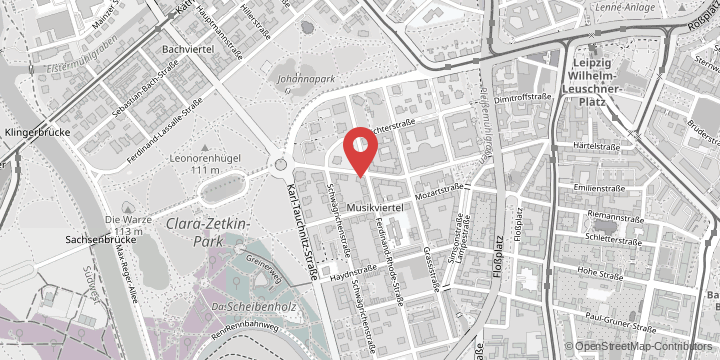

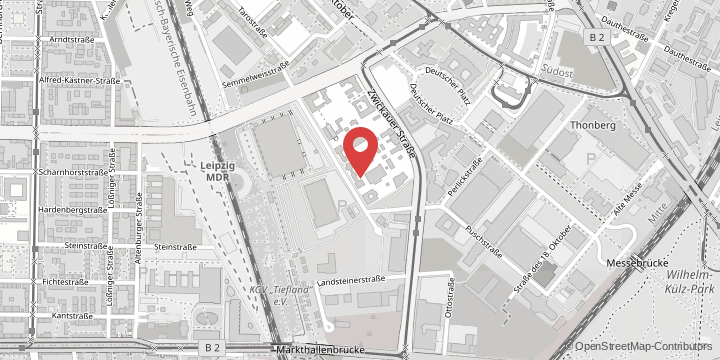

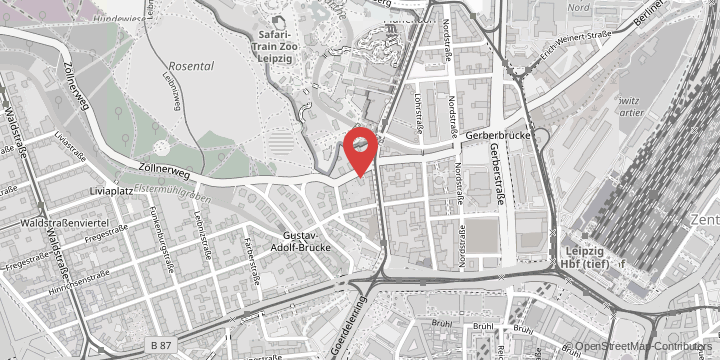

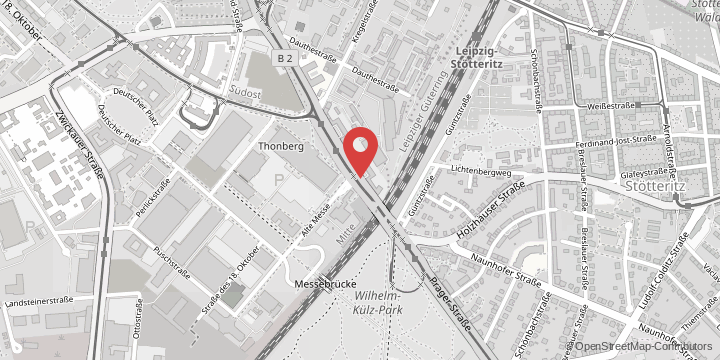

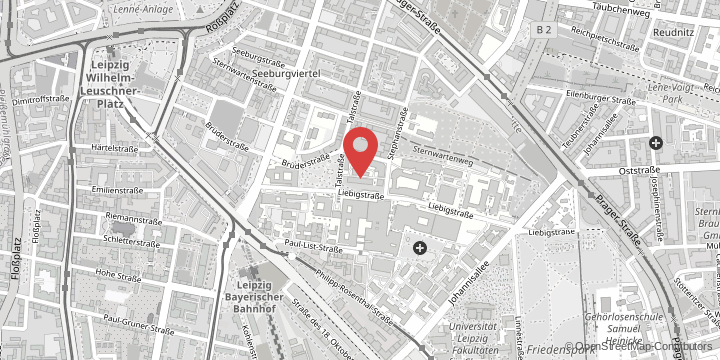

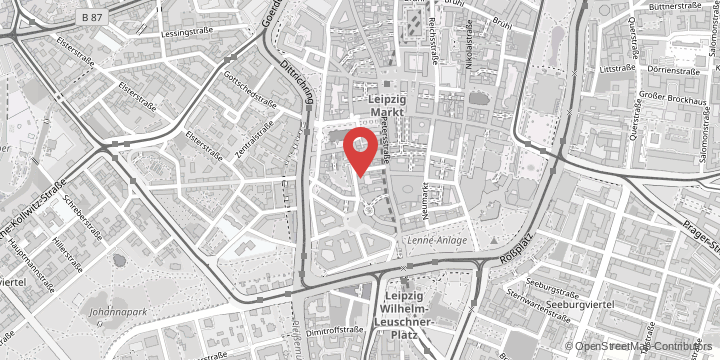

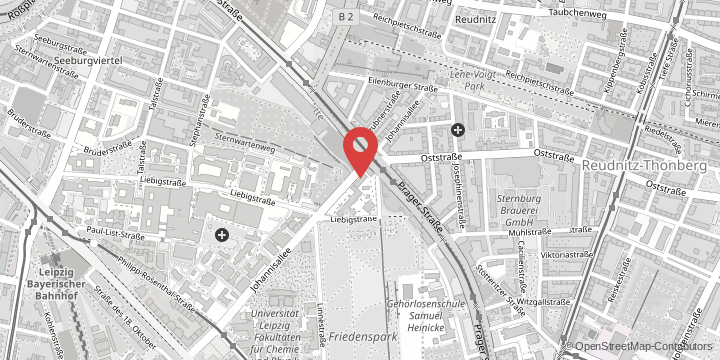

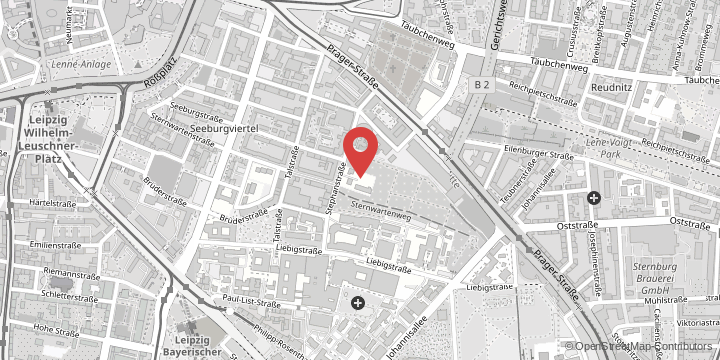

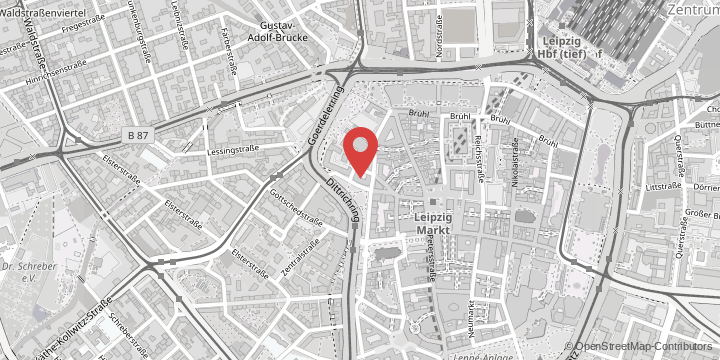

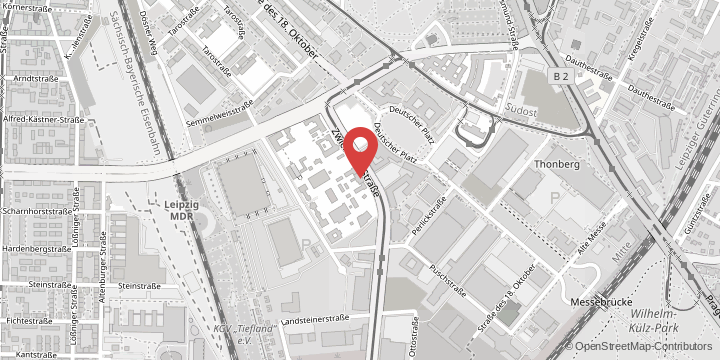

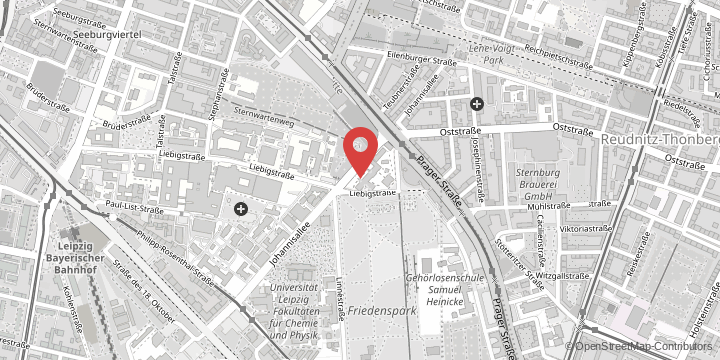

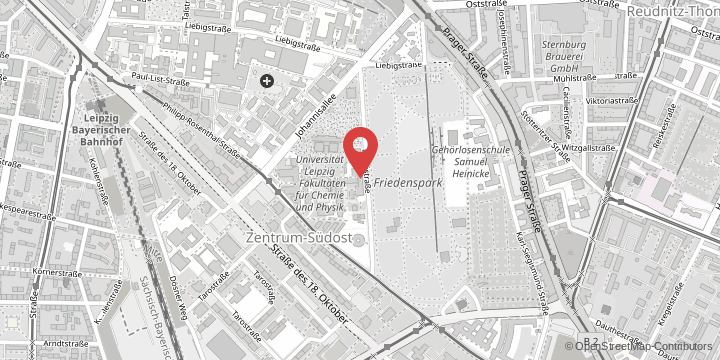

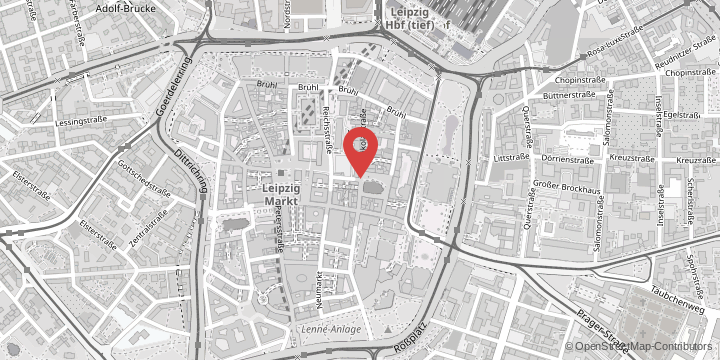

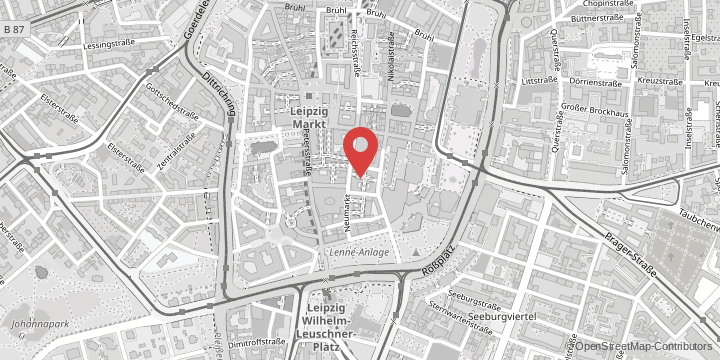

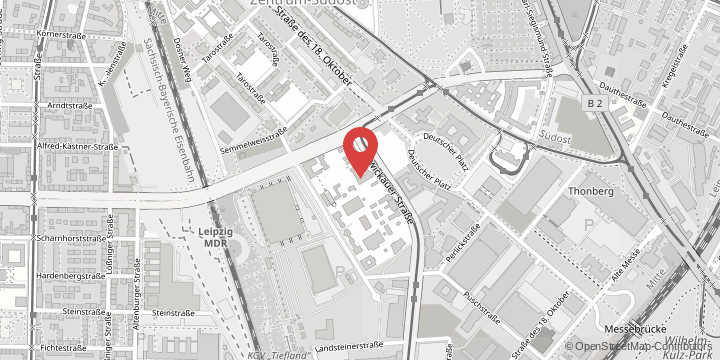

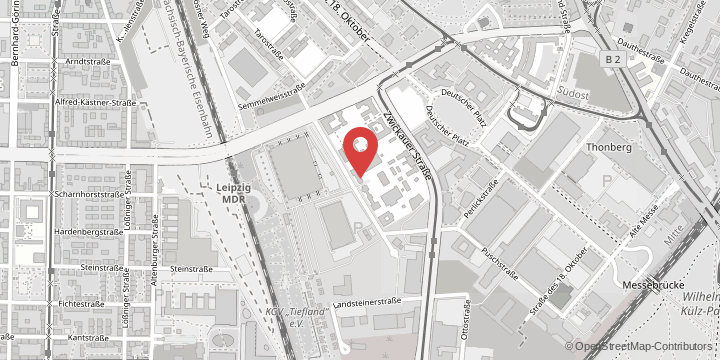

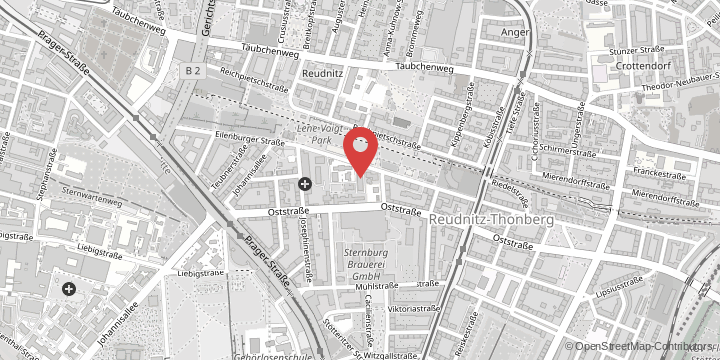

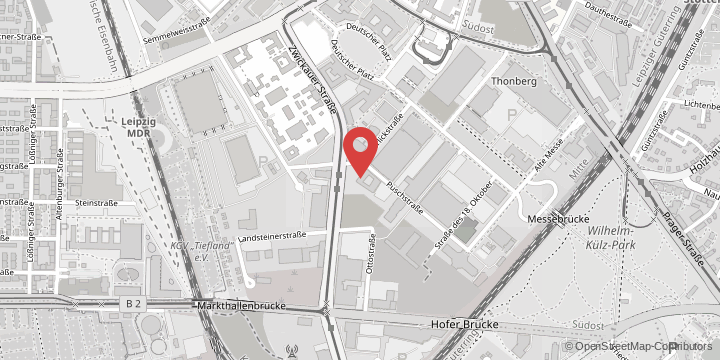

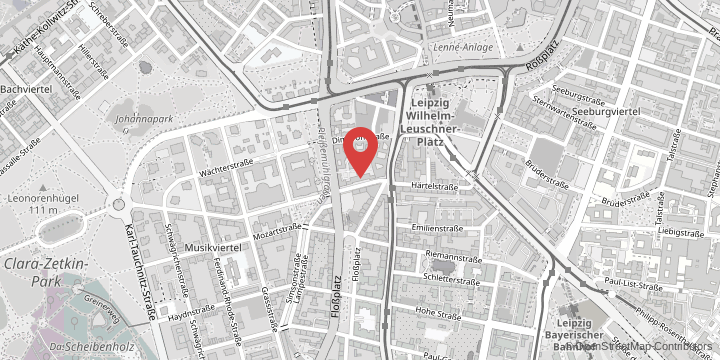

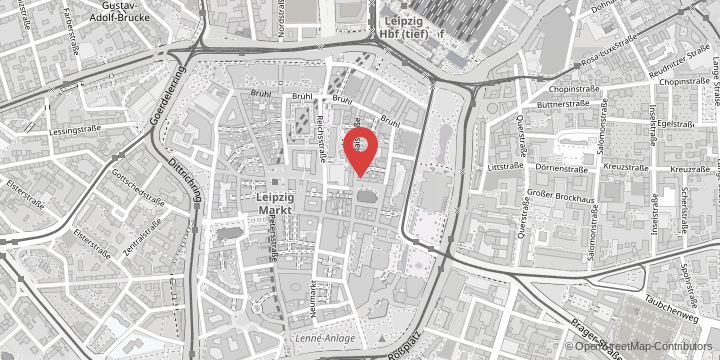

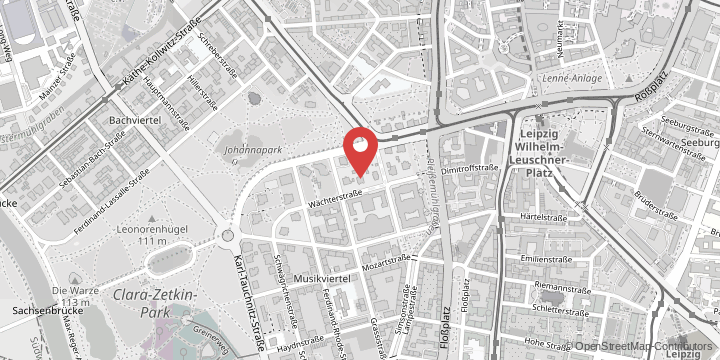

Dr Steffi Marung is PI of “‘Free radicals?’ Political mobilities and post-colonial processes of re-spatialization in the second half of the 20th century” at Leipzig University’s Collaborative Research Centre 1199, “Processes of Spatialization Under the Global Condition”. She is also involved in the planned New Global Dynamics cluster as part of the second competition phase of the Excellence Strategy of the German federal and state governments.