Although obese individuals are at greater risk of diabetes, high blood pressure or high cholesterol, not all obese people develop metabolic diseases of this kind. With around a quarter of all obese individuals healthy, scientists are trying to work out why some become unhealthy while others do not. Now, a comprehensive study by researchers from Zurich and Leipzig has provided a vital basis for this work. The researchers have produced a detailed atlas with data from healthy and unhealthy overweight people – on their fatty (adipose) tissue and on the gene activity in this tissue’s cells.

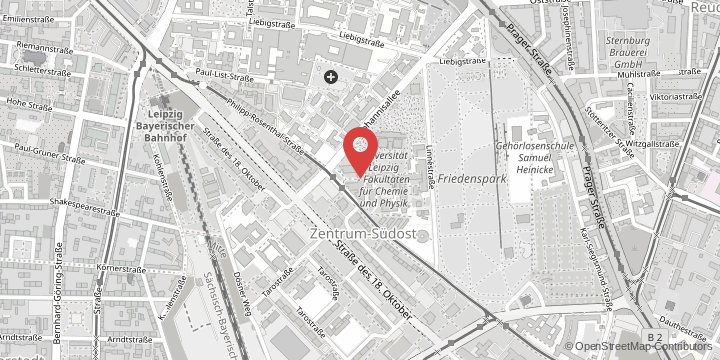

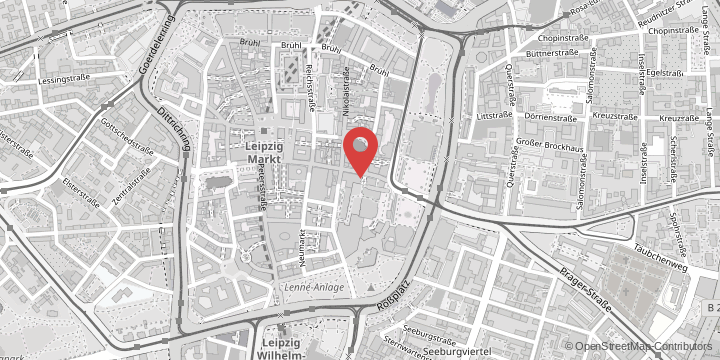

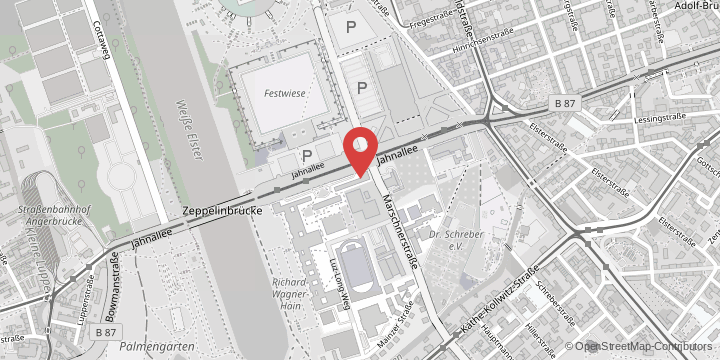

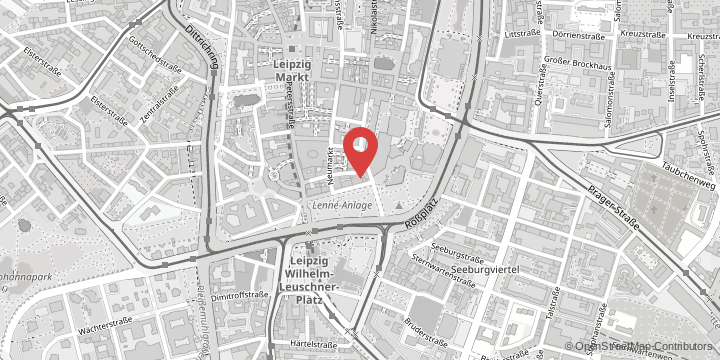

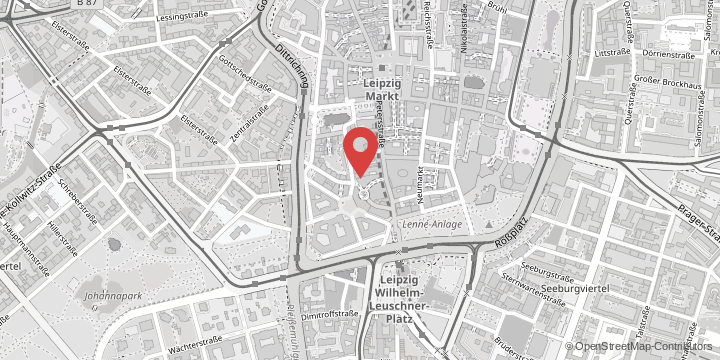

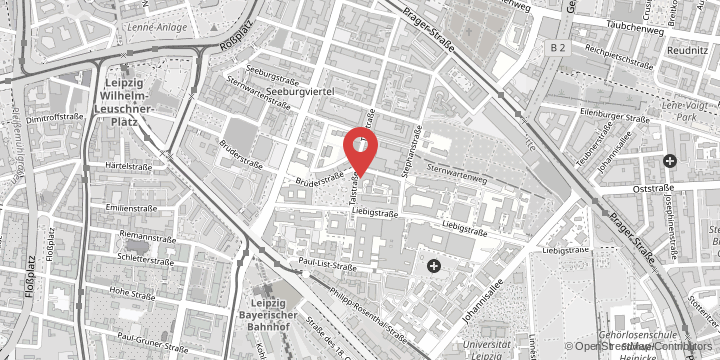

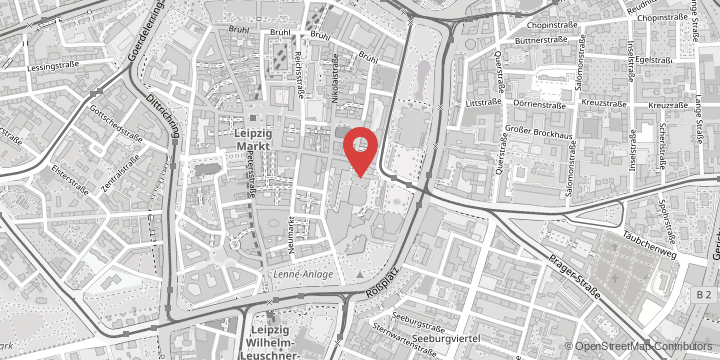

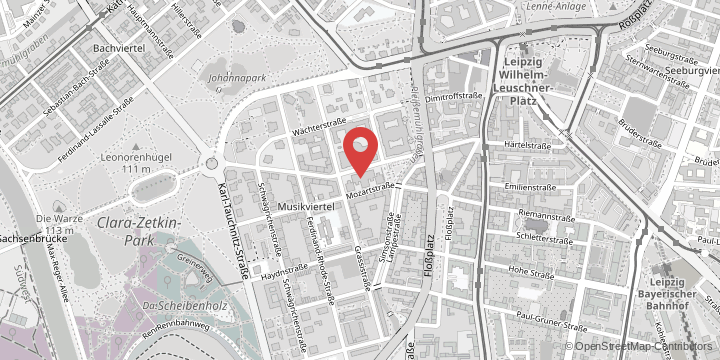

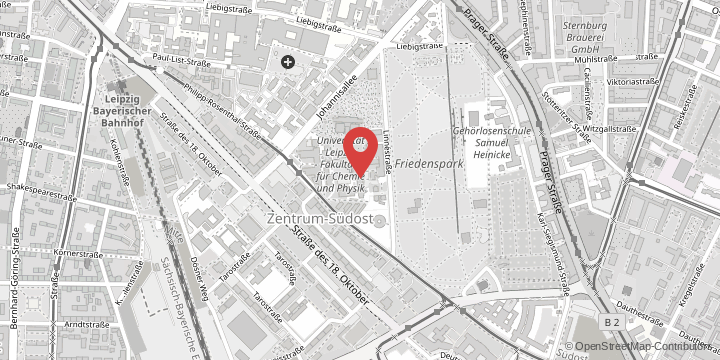

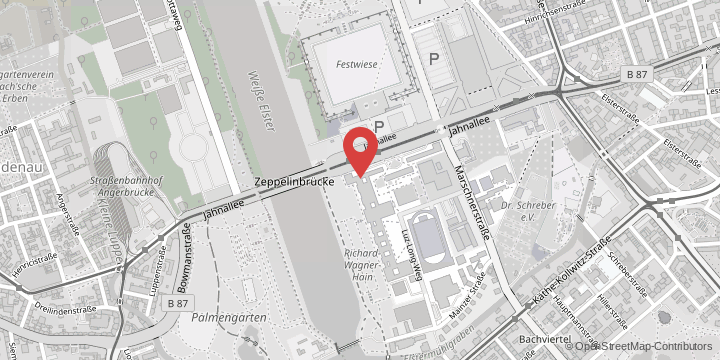

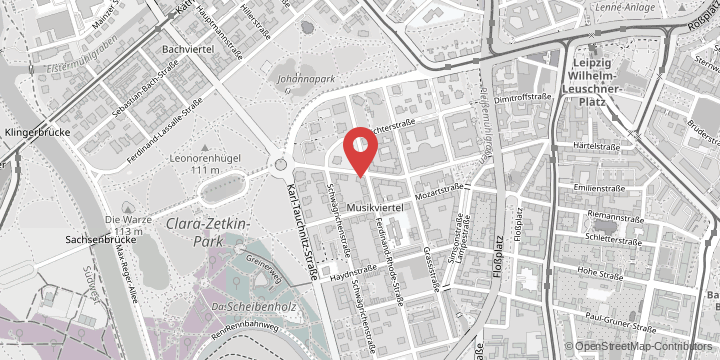

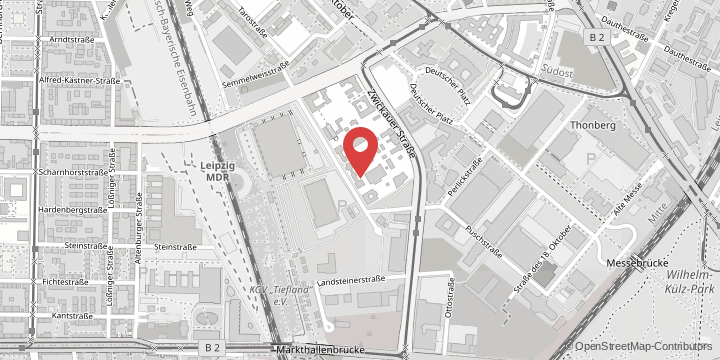

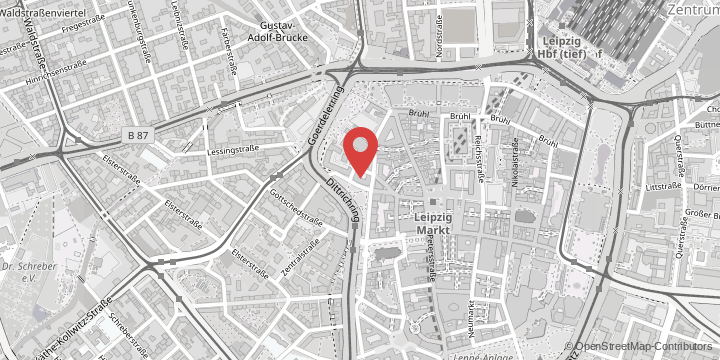

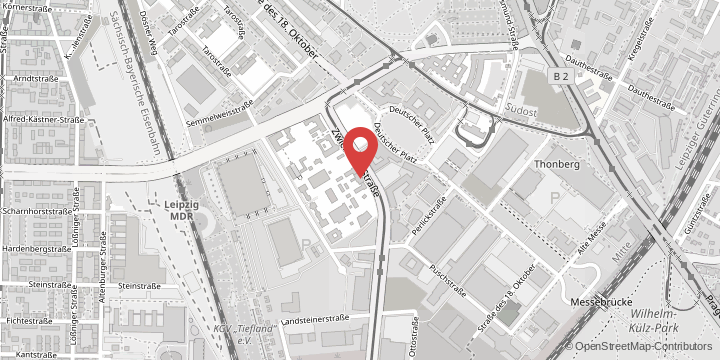

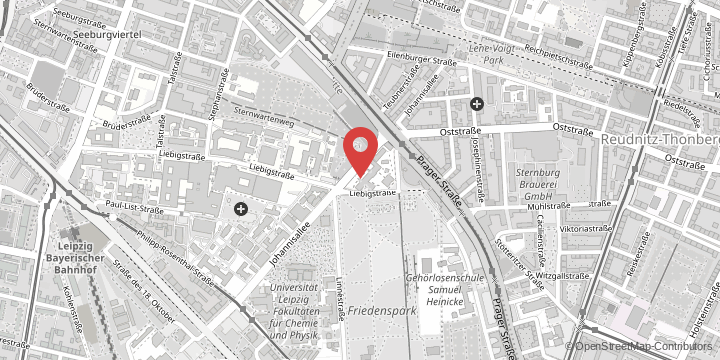

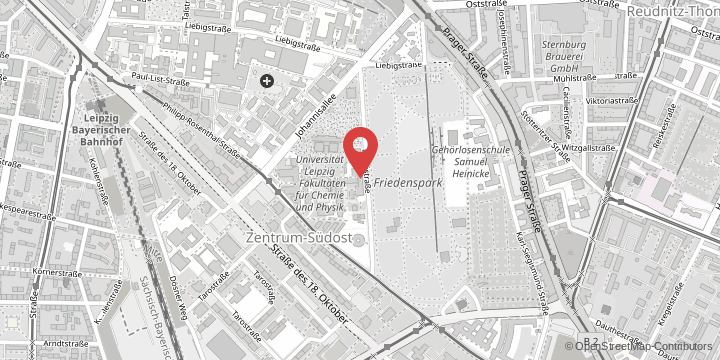

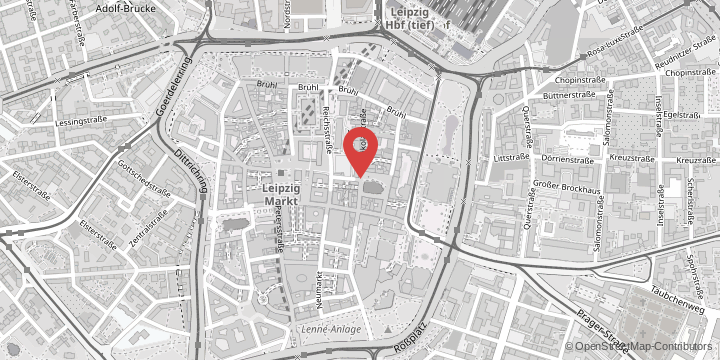

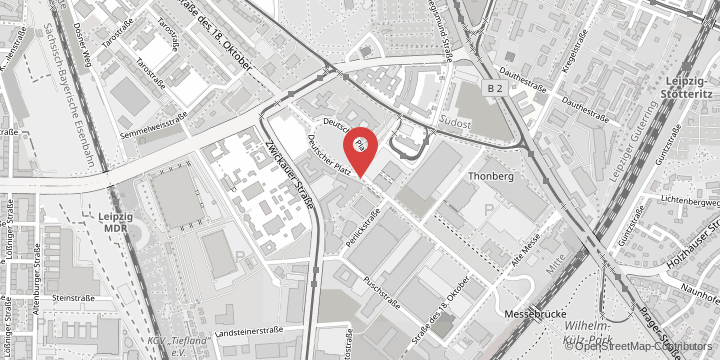

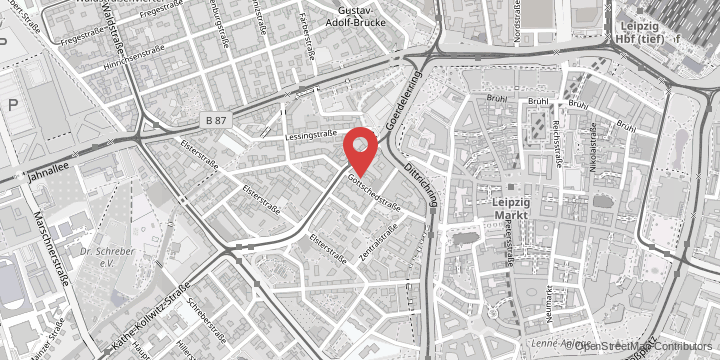

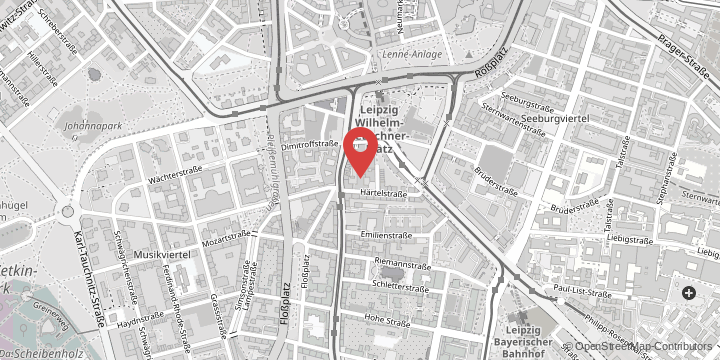

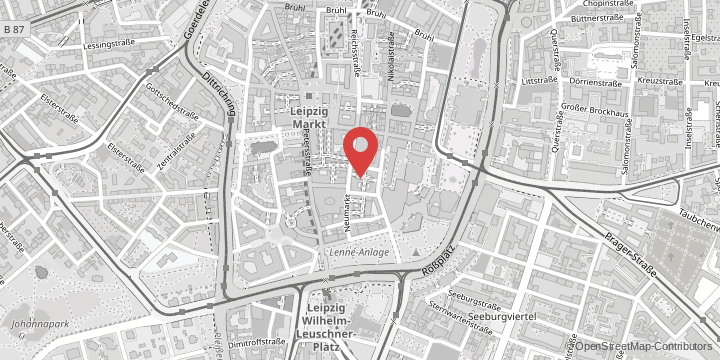

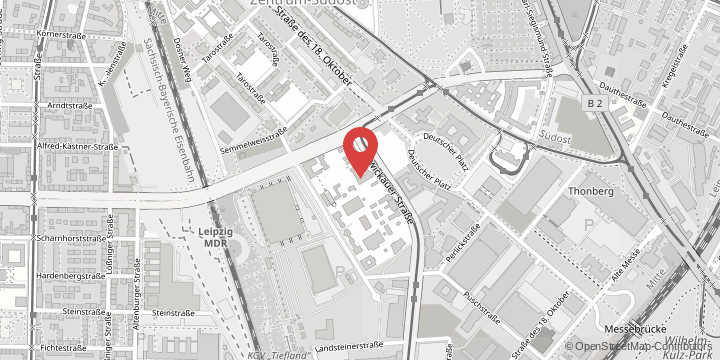

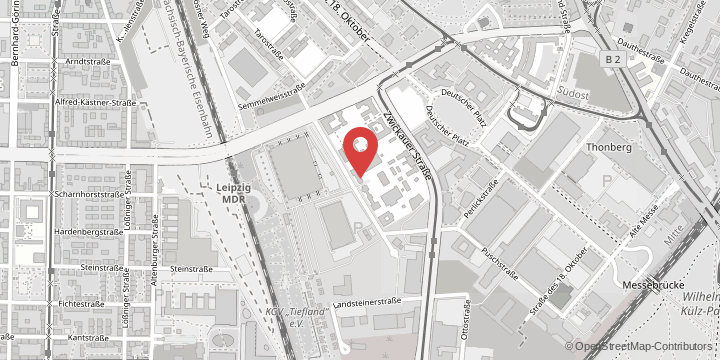

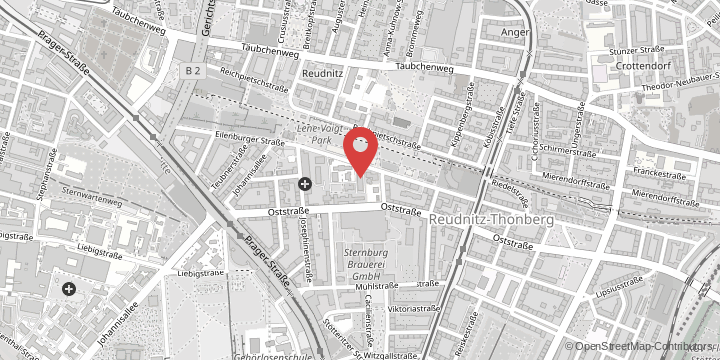

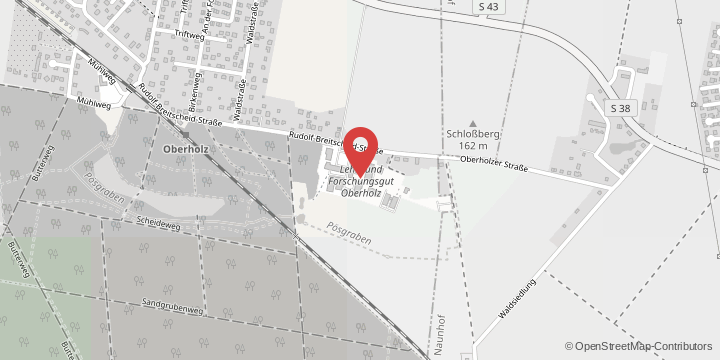

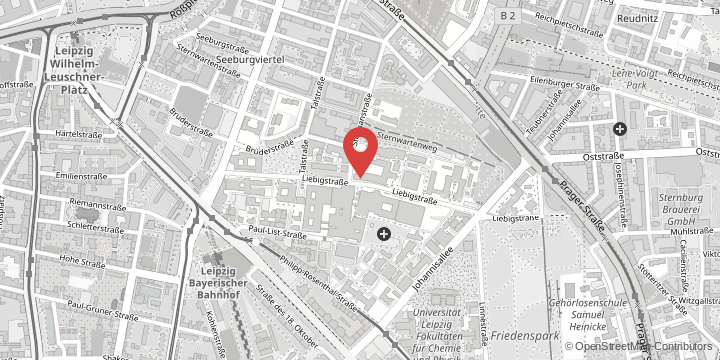

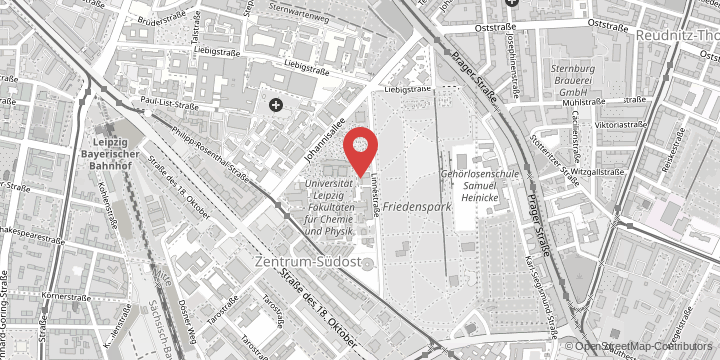

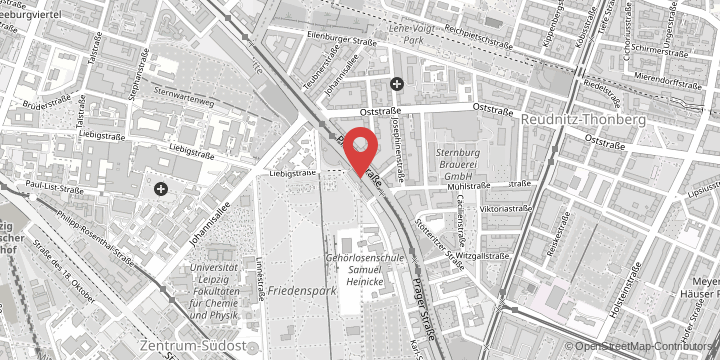

The study used an extensive collection of biopsies from obese individuals taken from the Leipzig Obesity BioBank, which is run by Leipzig University, the University of Leipzig Medical Center and the Helmholtz Institute for Metabolism, Adiposity and Vascular Research (HI-MAG). These samples were compiled by scientists from Leipzig University. “They come from obese patients who have undergone surgical procedures and have consented to the collection of adipose tissue samples for research purposes. The collection also contains extensive medical information about the patients’ health,” explains Professor Matthias Blüher, Professor of Clinical Obesity Research at Leipzig University and co-leader of the study.

As the tissue samples were taken from obese people with and without metabolic disease, they allow comparison between healthy and unhealthy obese people. Using samples from 70 volunteers, the researchers examined which genes were active on a cell-by-cell basis in two types of fatty tissue: subcutaneous and visceral. Scientists and medical experts assume that visceral fat, which lies deep in the abdominal cavity and surrounds the internal organs, is primarily responsible for metabolic diseases. In contrast, experts generally believe that fat located just under the skin is less problematic.

Significant changes in the fatty tissue of the abdominal cavity

The researchers were able to show that there are significant functional changes in the cells in the visceral fat of people with metabolic diseases. This remodelling affects almost every cell type in this form of tissue. For example, the genetic analyses showed that the fat cells of unhealthy people were unable to burn fat as effectively and instead produced higher levels of immunologic messenger molecules.

The researchers also found very clear differences in the number and function of mesothelial cells: healthy obese people have a much higher proportion of mesothelial cells in their visceral fat, and these cells are more functionally flexible. In healthy people, they can switch into a kind of stem cell mode and become different types of cells, such as fat cells. Finally, the researchers also found differences between men and women: a certain type of progenitor cell is only present in the visceral fat of women.

Finding new biomarkers

The new atlas of gene activity in overweight people describes the composition of cell types in fatty tissue and their function. “However, we cannot say whether these differences are the reason why someone is metabolically healthy or whether, conversely, metabolic diseases cause these differences,” says Professor Blüher. Instead, the scientists see their work as a basis for further research. They published all the data in a freely accessible web application so that other researchers could work with it.

In particular, new markers can now be found that provide information about the risk of developing a metabolic disease. These could also help improve the treatment of such diseases. For example, there is a new class of drugs that inhibit appetite and stimulate insulin secretion in the pancreas – but such medication is in short supply. “Biomarkers that can be derived from our data could help to identify those patients who are most in need of such treatment,” says Professor Blüher.