Why are you interested in taking a global view of ‘social cohesion’? With all the challenges we face today, why is this relevant to us in Germany?

Initially, in 2015–16, the social cohesion debate appeared as a specifically German response to the challenges posed by the Pegida movement and the AfD political party. Soon there was talk of the danger of a divided and polarised society, and virtually all parties and politicians espoused the ideal of social cohesion, however vaguely defined. Since then, we have seen a rapid spread of calls for social cohesion in the face of mostly right-wing populist movements, regimes and leaders – from Trump in the US to Orbán in Hungary to Kais Saied in Tunisia.

At the same time, the Chinese Communist Party, for example, is forcing a debate on how to create and expand social cohesion while also rejecting Western notions of cohesion. So our German discourses on social cohesion are part of a global debate about politics and democratic participation in the future. It is worth taking a closer look at the arguments and motives that inform our definition of social cohesion. As appealing as it may seem at first glance, the term is not immune in its meaning to totalitarian, nationalist, xenophobic and other facets that restrict individual rights of freedom.

How is this concept viewed in the international research community, and what are the regional differences?

Attention to populist movements and regimes has grown almost exponentially in many parts of the world in recent years, as their growth challenges regional and national political systems as well as the formats of the international order. However, there are significant differences between the diagnoses of populism.

Interestingly, however, the ability and willingness of many populists to form alliances is enormous, even if this seems improbable given their programmes and principles. We see this in the EU Parliament, but also in the BRICS+ meeting and in the coalition of military juntas in the Sahel. And many are eagerly awaiting the outcome of the next US presidential election before hazarding any predictions about social cohesion in the United States.

Interestingly, however, this initially leads to a fragmented research discussion in which each case is discussed individually, but the global context does not seem to be of much interest – apart from the observation that populism is everywhere. This is mainly because, firstly, the respective historical and socio-economic contexts are indeed very different and, secondly, the global comparison requires cooperation between different regional experts in a joint project, which often does not exist.

The first FGZ funding period will come to an end in a few months’ time. In your opinion, what makes research at the FGZ and especially at the Leipzig site so special?

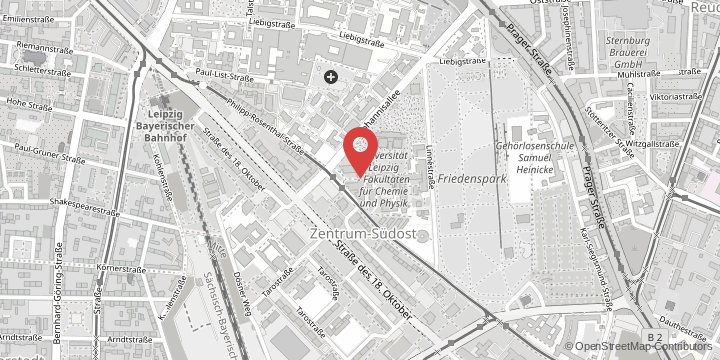

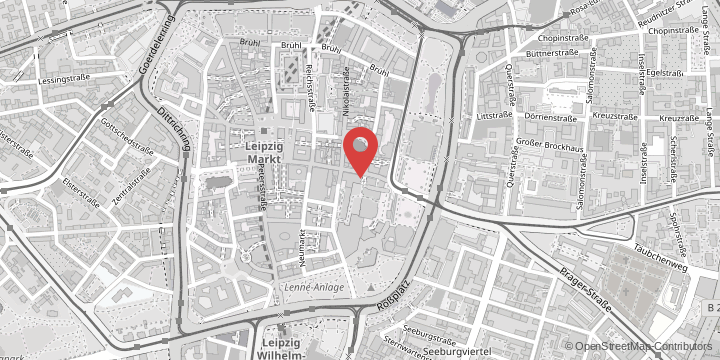

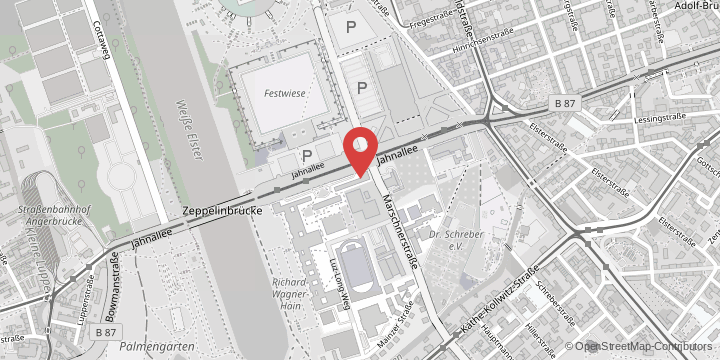

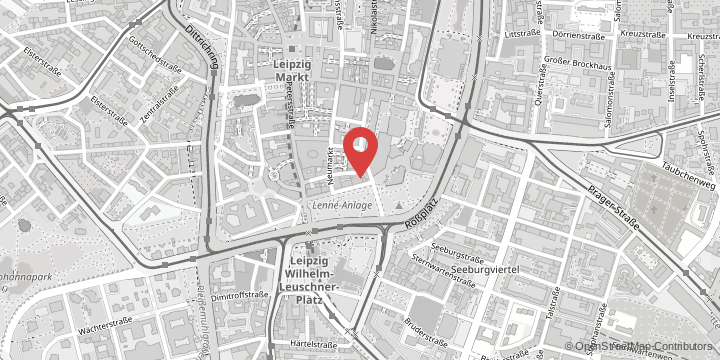

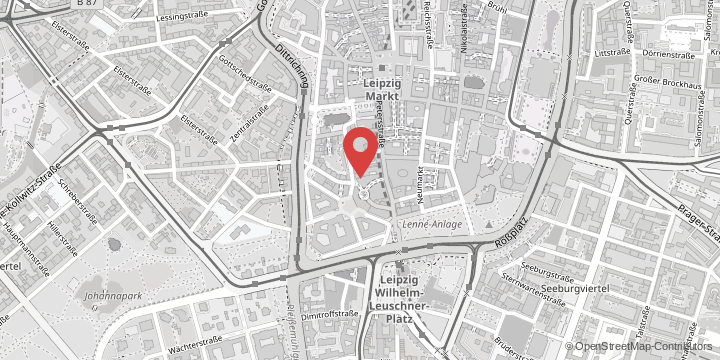

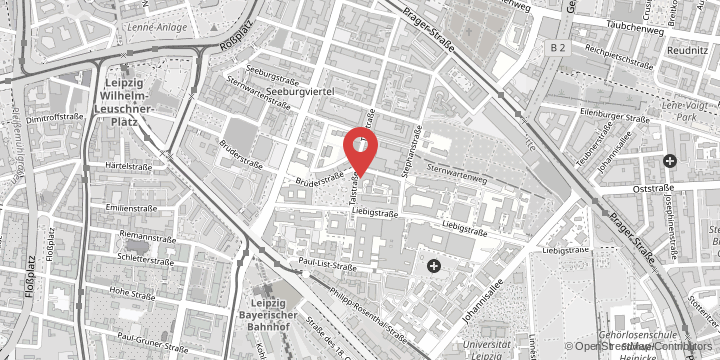

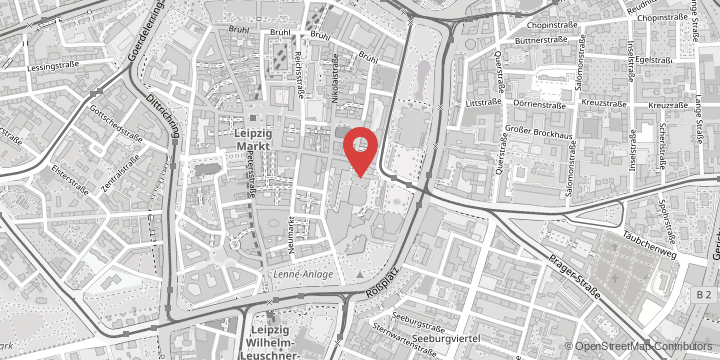

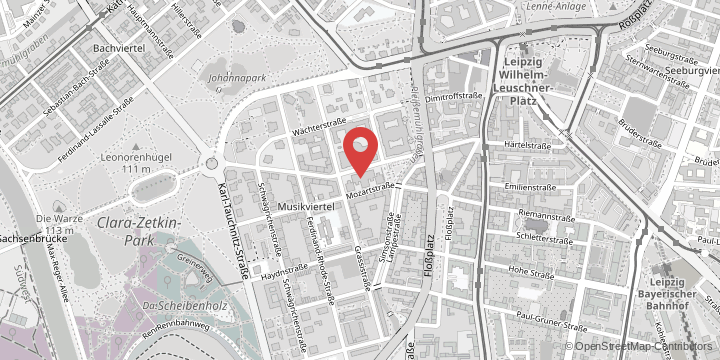

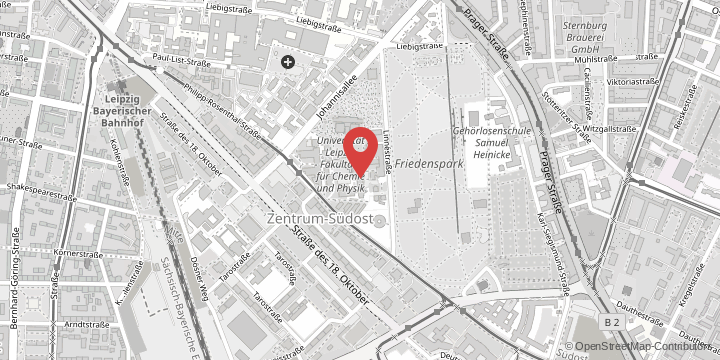

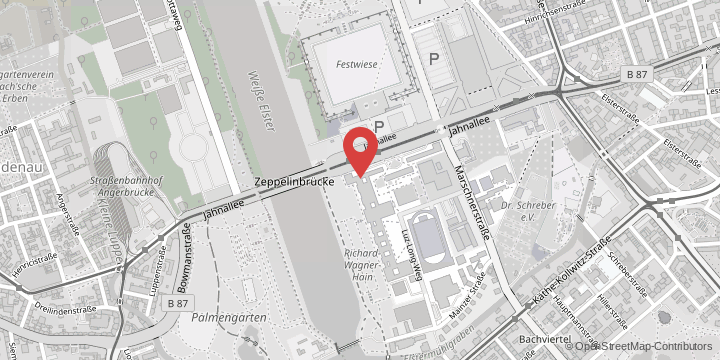

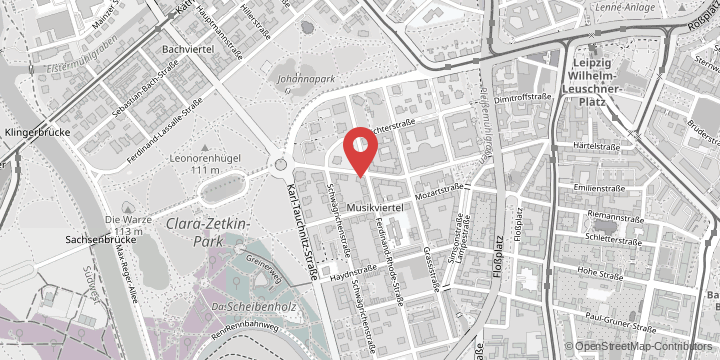

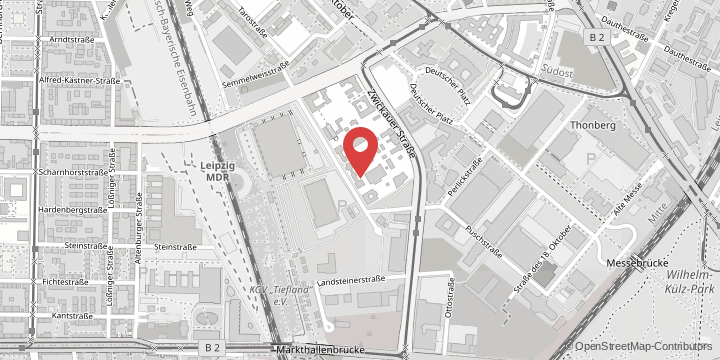

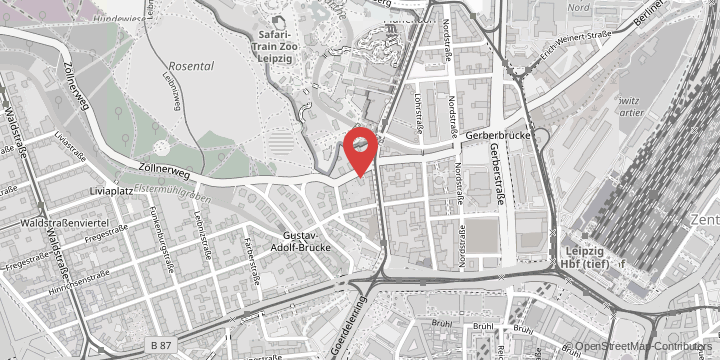

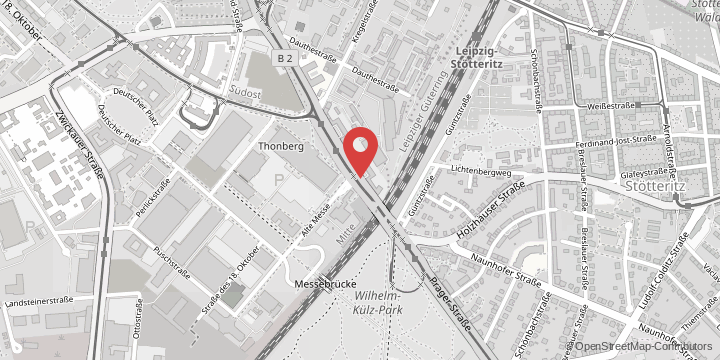

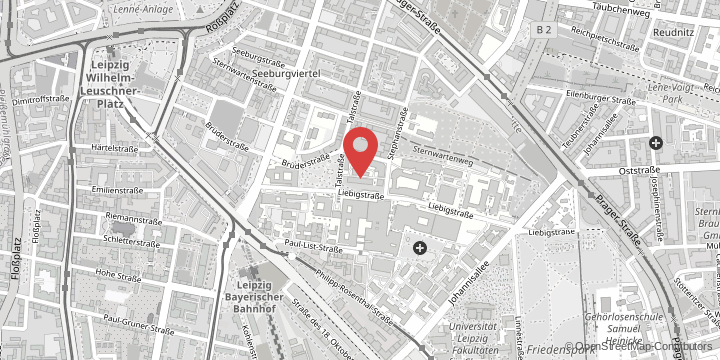

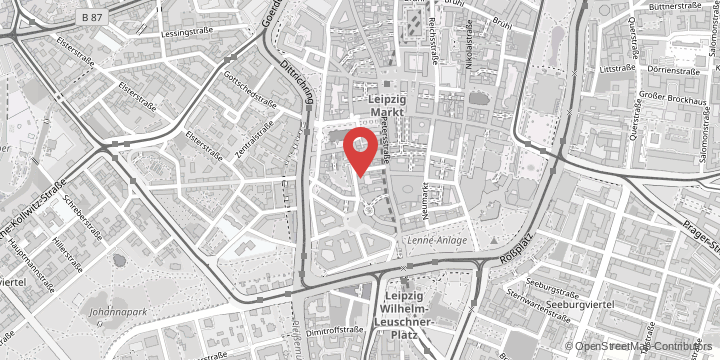

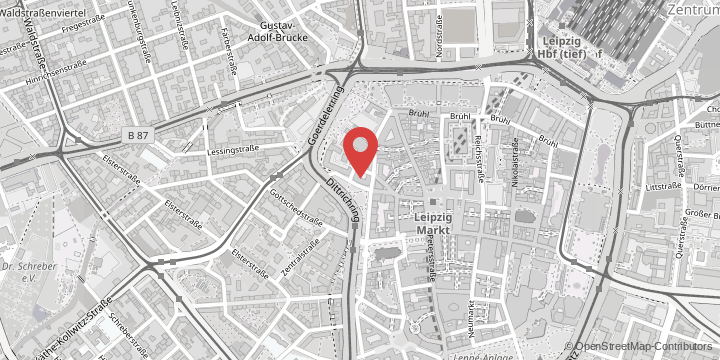

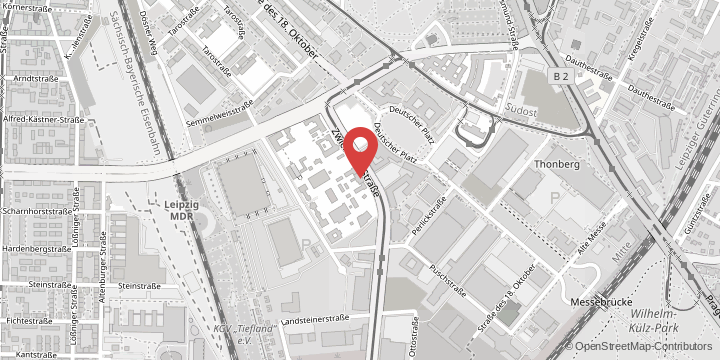

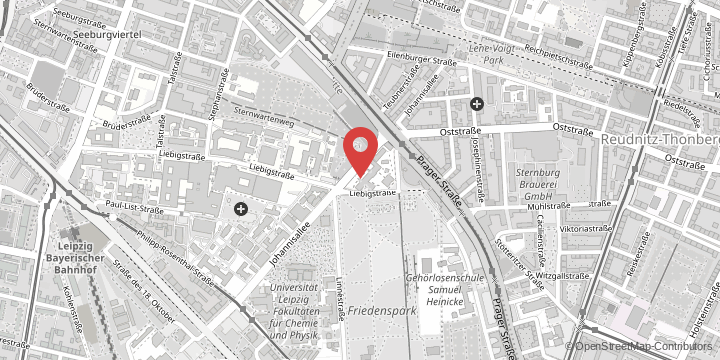

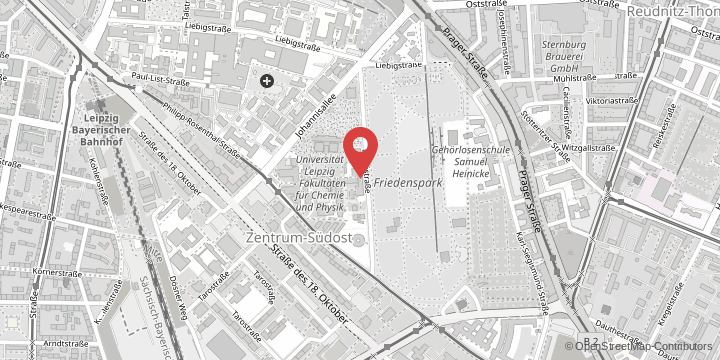

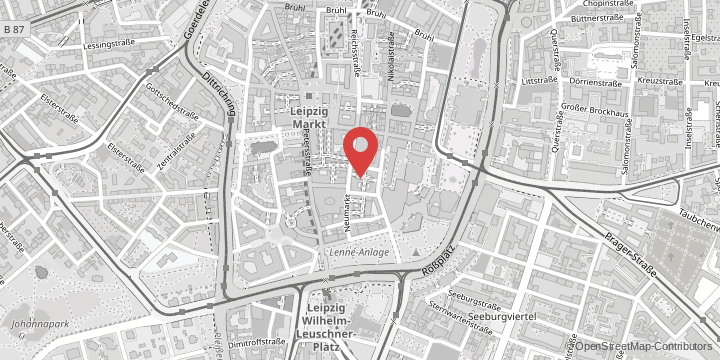

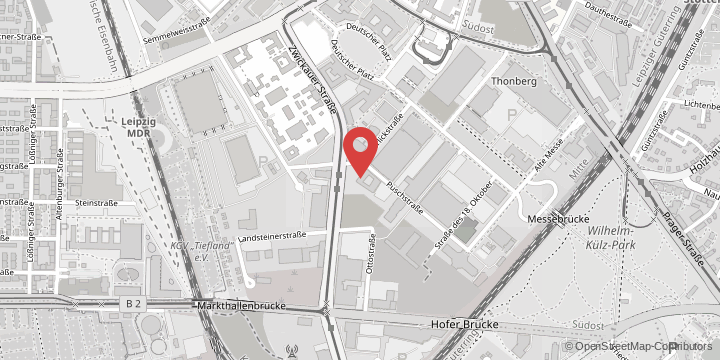

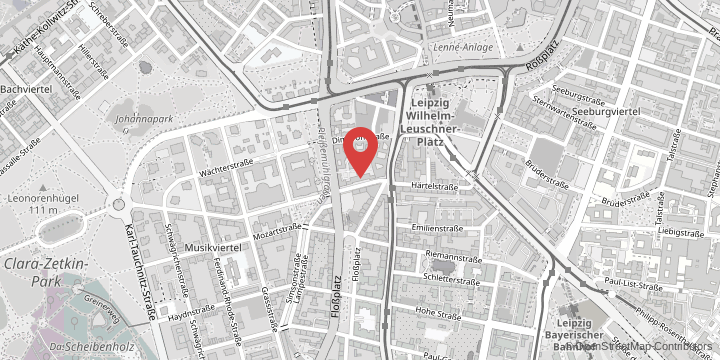

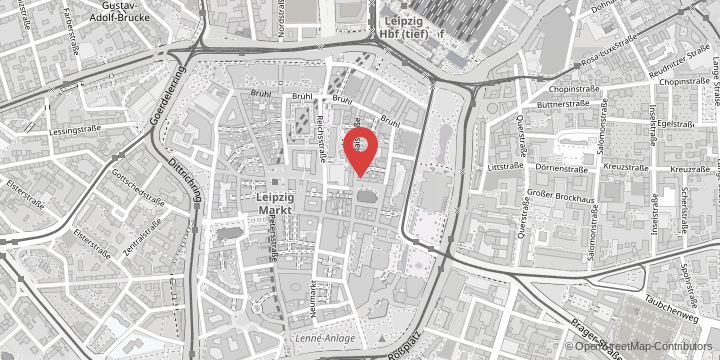

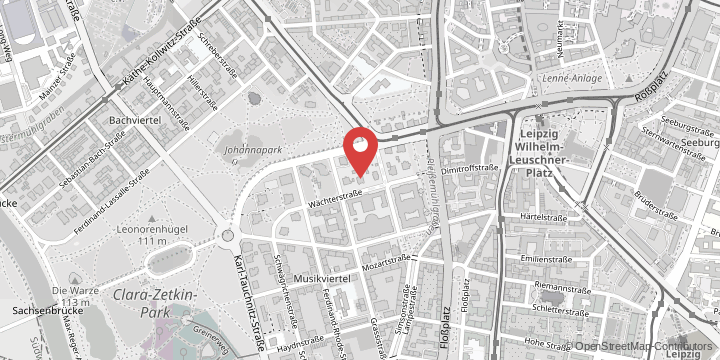

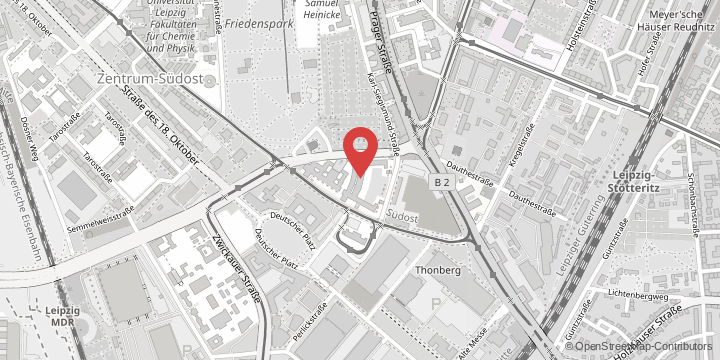

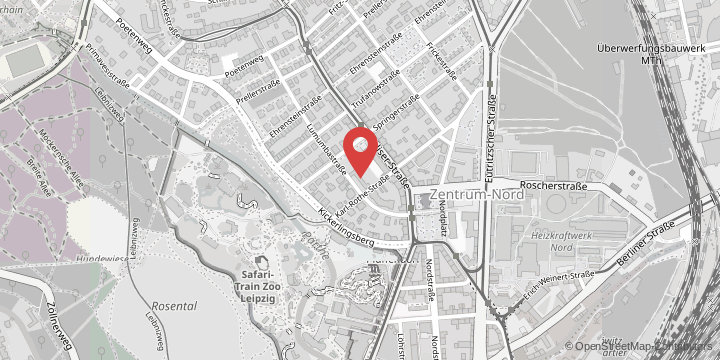

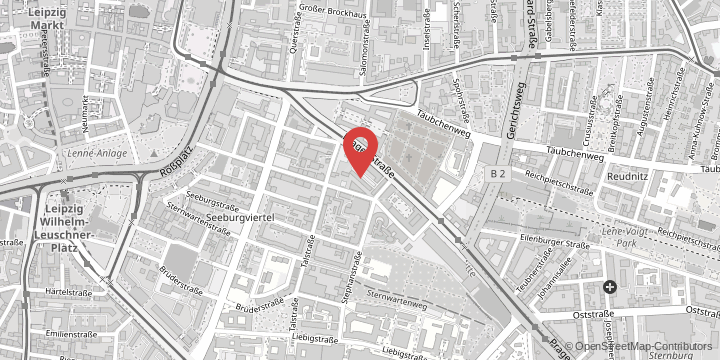

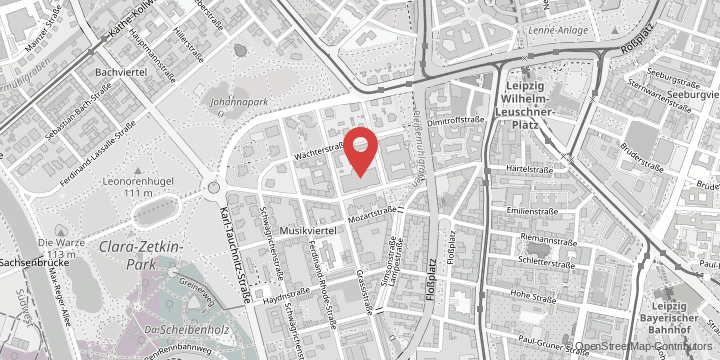

Leipzig University has contributed to the FGZ – a state-funded research institute with eleven locations – with a large number of specialisations. These range from extremism and historical research, social psychology and the study of the promise of equality from an economic and social science perspective, to area and global studies. With its profile of analysing dynamics that can be observed on a global scale, the Leipzig location is particularly active in opening the FGZ beyond German navel-gazing. We do this by contributing empirical research on Eastern and Western Europe, China, the US and sub-Saharan Africa, thus generating new questions that an in-depth study of the German case alone might not even raise.

The concept of social cohesion has seen a remarkable rise in recent years to become a central buzzword in political and social science debates. As a historian, how do you explain this rise, what might it be linked to?

Initially, the term was a response to a certain confusion within political systems and the growing vote share of right-wing populist parties. But by now you have to draw the radius wider. It seems to me that in the desire for ‘social cohesion’ we are negotiating how we want to deal with the challenges and impositions of the 2020s: the often ideological euphoria of globalisation has waned, but at the same time a complete withdrawal from the interdependencies that have emerged is hardly realistic.

The failure of the promise that ‘globalisation’ would bring eternal peace, prosperity for all sooner or later, and a new world order of automatic balancing of interests needs to be processed. So for the time being, global society does not have the answers. It seems obvious to return to society in its old national guise – but its borders have become porous in a very different way than the dream of closed entities would have us believe.

At the same time, the experience of the pandemic and the horrors of climate change urge us to cooperate more, not less. Hence the need to rethink how we live together locally, in nation states and on the planet. It is a discursive coincidence that this time we do this in terms of social cohesion, as we did in previous eras, for example, around the central concept of solidarity or that of the nation. The problem has evolved historically, but it has also remained the same in essence – how do you adjust participation and cooperation?

What do researchers advise? What can be done about increasing polarisation and the breakdown of social cohesion?

The diagnosis alone seems questionable to me. The fact that we are discussing and arguing politically shows the scale of the challenge and the fact that no one can claim to know the definitive solution. If we no longer experience conflict in such a situation, then development has probably come to a standstill. Whether every form of conflict is optimal is another question altogether. But my advice is to cheerfully accept that conflict is necessary and should be conducted with composure – it is the best form of social cohesion we have, both in Germany and in the many global settings. I think the dream of social cohesion without political disagreement about the best solutions is dangerous – history is full of examples of how this has gone wrong.

Political disagreement, however, is the opposite of what is often described as polarisation, because in extremely polarised situations, the other side is denied the right to possibly also be right, or even the right to have a say. When societies fall into this state, they deprive themselves of crucial development opportunities that only come from a constant willingness to learn.

The research institute

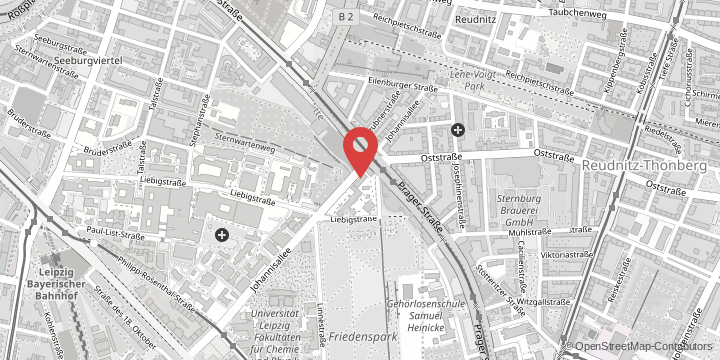

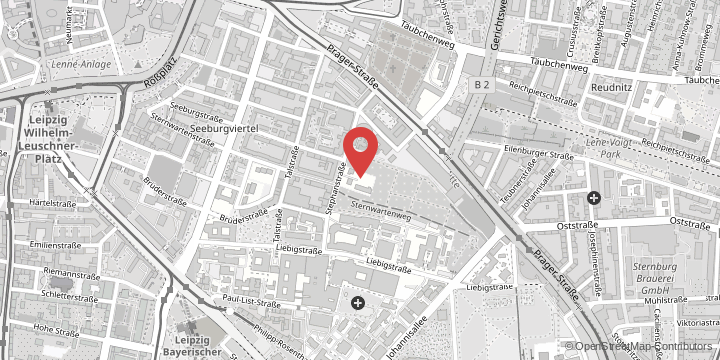

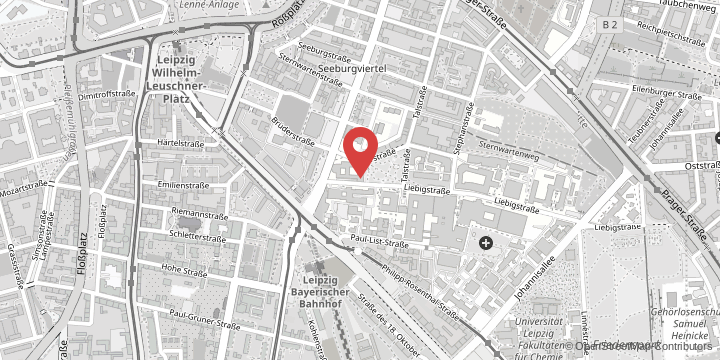

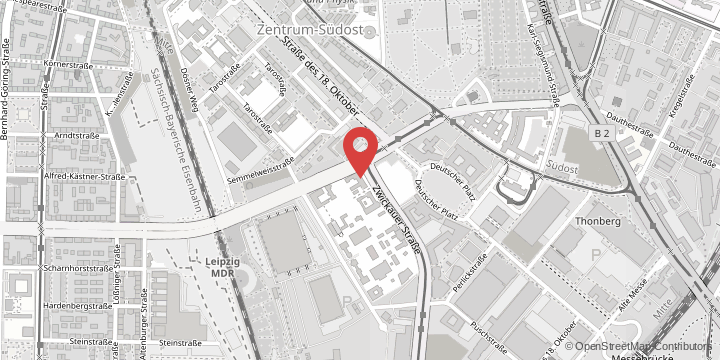

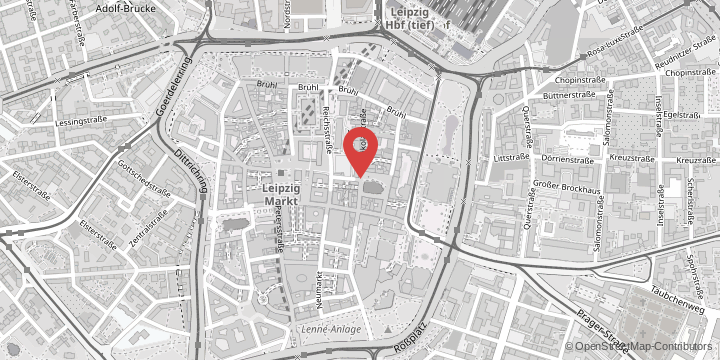

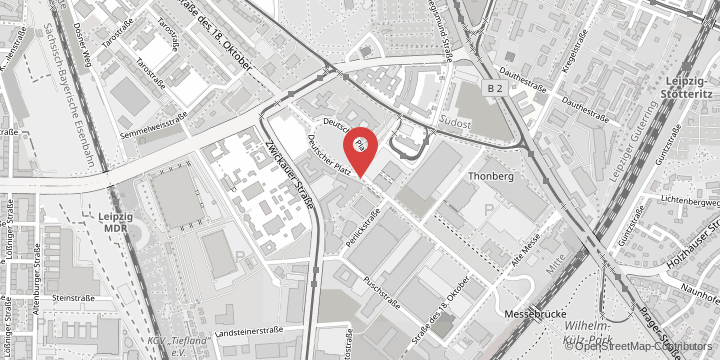

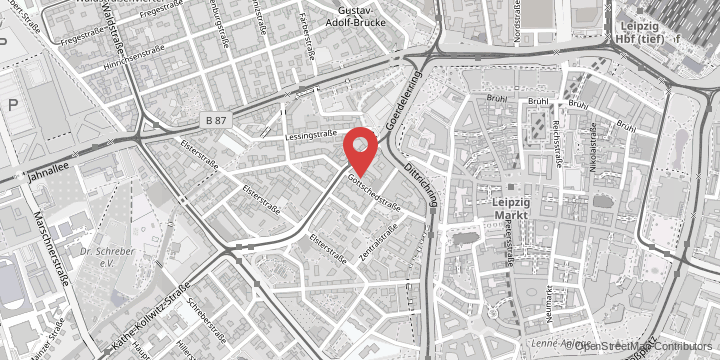

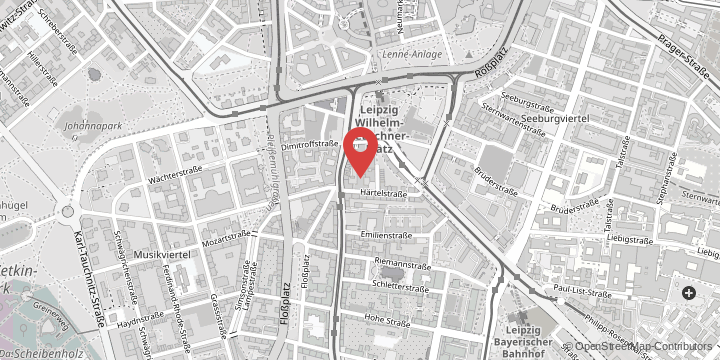

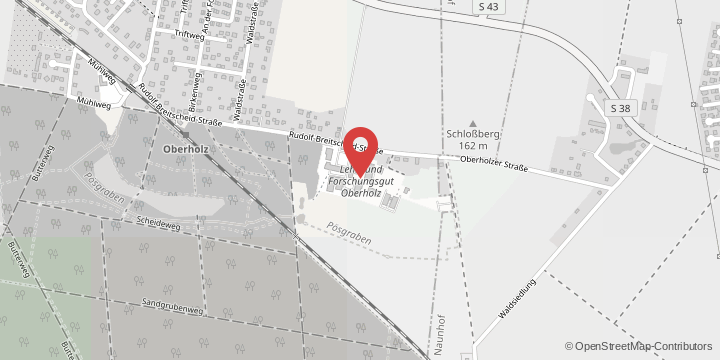

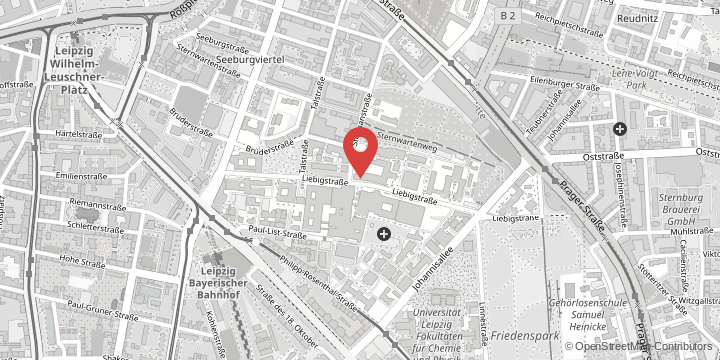

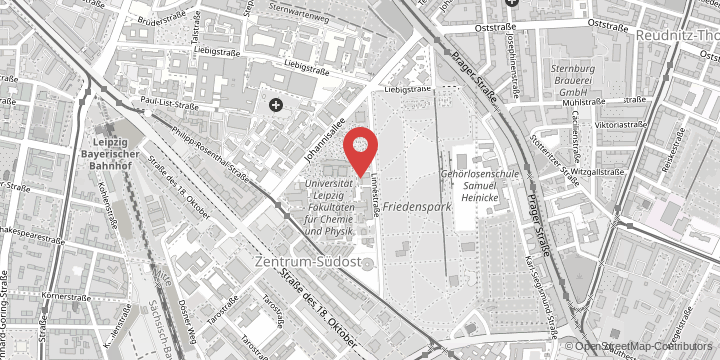

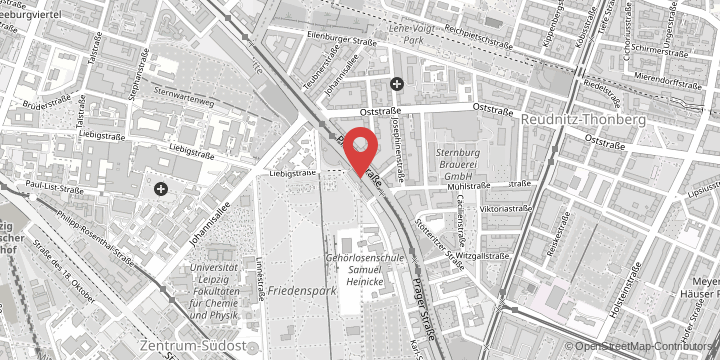

At the Research Institute for Social Cohesion (FGZ), more than 200 researchers work on issues of social cohesion: identities and regional worlds of experience, inequalities and solidarity, media and conflict culture, polarisation and populism, but also anti-Semitism and hate crime. The FGZ, which was set up by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research in 2020, has eleven locations across Germany. The Leipzig sub-institute is based at the Leipzig Research Centre Global Dynamics and consists of about 20 scientists. In 14 interdisciplinary projects, they examine the diversity of populist movements and regimes and their popular acceptance from the late 19th century to the present. These include case studies for Western and Eastern Europe, the two Americas, sub-Saharan Africa and East, South and Southeast Asia, with the intention of placing developments in Germany in a broader, ultimately global context.