Legal proceedings against radical right terrorism taking place in Halle (Germany), and Christchurch (New Zealand), in August 2020 might seem quite disconnected from the final sessions in the trial of Ratko Mladić in front of the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT), 25 years after the end of the Bosnian War. And yet, there is a connection between their narratives, one developed in radical right internet platforms (like imageboard 4chan), via online manifestos and memes, about which we are only beginning to learn. This text sheds some light on usages of Serbian military in the Bosnian and Kosovo wars as a symbol of struggle against Muslims in the Great Replacement theory of the radical right [1] on the internet.

On 25 August 2020, a two-day hearing began for Ratko Mladić’s appeal against conviction of genocide and crimes against humanity issued three years earlier. Crimes against Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) were committed during the Bosnian War (1992–1995), under Mladić’s military command. In 2016, Radovan Karadžić, Bosnian Serbs’ political leader, was given a life sentence for genocide and crimes against humanity. On 24 August 2020, a sentencing hearing began of Brenton Tarrant, the man who killed 51 people at two mosques in New Zealand in 2019. On 26 August, a process started in Magdeburg against Stephan Balliet, who attacked the synagogue in Halle in October 2019, killing two passers-by.

At a first glance, nothing but a coincidental time of trial proceedings connects the crimes committed in the war in Bosnia with terrorist attacks in New Zealand or in Halle. Even when stretching the ideology of the extreme right, terrorist attacks have little in common with systematic crimes and mass murder committed by an army in war. And yet, the radicalization of both Balliet and Tarrant, as well as Anders Behring Breivik almost a decade earlier, originated in radical right internet circles, via mems and humorous songs shared on 4chan, 8chan, Reddit, and similar platforms, where Mladić and Karadžić serve as “prominent role models” in the fight against Muslims and refugees – and by extension against any non-white, non-Christian group. This “fascination with Balkans”, as it was described in media, became evident only after the attacks, when terrorists acknowledged that their inspiration stems from the Serbian war against Muslims in Bosnia and Kosovo.

#Remove Kebab

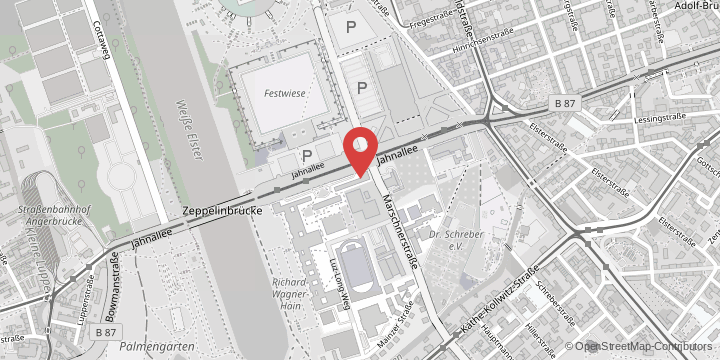

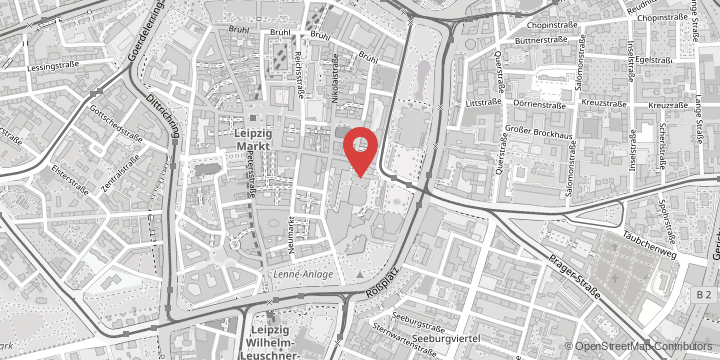

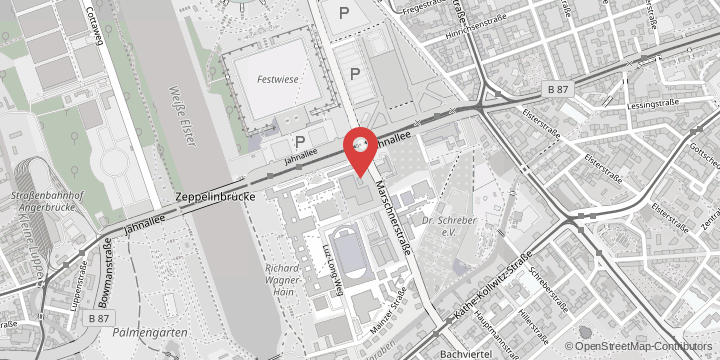

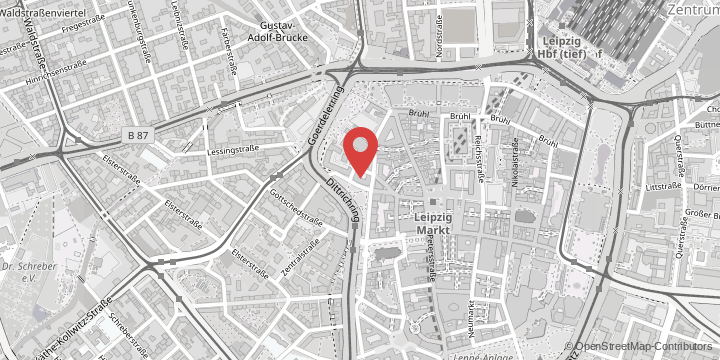

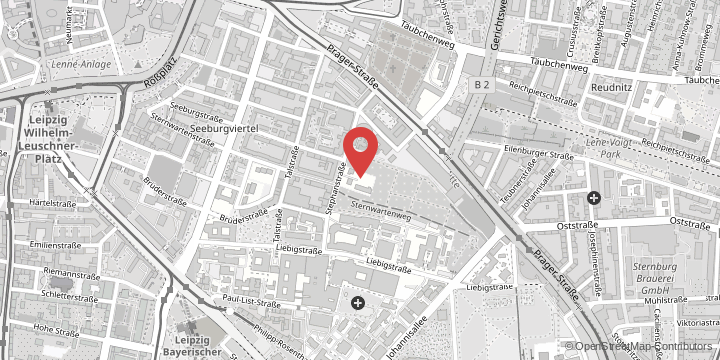

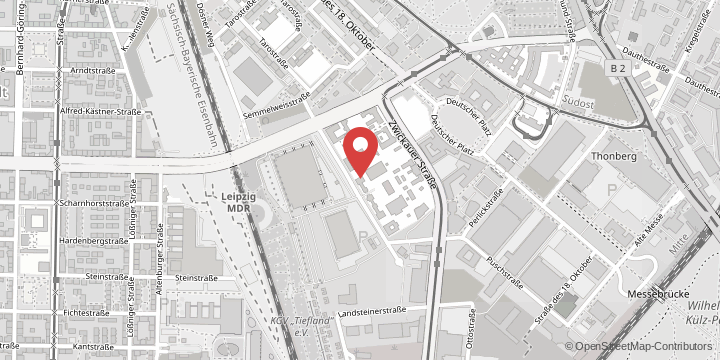

Brenton Tarrant, an Australian radical right terrorist, streamed a video of the entire slaughter in New Zealand on social media, starting with the car ride to the mosques, during which he was listening to a Serbian song, with the names of fourteenth-century Serbian medieval fighters against the Ottoman Empire engraved on his weapons. When Tarrant referred to himself as a “Kebab removalist”, only a few of his internet radical right fellows could decipher the meaning of the phrase. Soon after the gruesome attack, media discovered that it refers to the song “God is a Serb/Serbia strong”, which turned into a meme under the “Remove Kebab” slogan. It was recorded during the war in Bosnia by four soldiers from Republika Srpska singing in honour of Karadžić, supporting the war against Muslims in Bosnia. The song starts with declaration that Serbian land is attacked by “Croatian Ustashas and Turks”, calling upon Karadžić to lead the Serbs and show the enemy that they are not afraid of anything. It warns Croatian Ustashas not to touch Serbian land, while telling them to be aware/be afraid as Serbian fighters are coming to defend Serbian people, fighting for glory and freedom. In some of the edited versions, the image of Karadžić from the Hague is inserted in the video (image 1, frame 2b).

According to the knowyourmeme.com website, the video was posted online in 2006, and it quickly gained popularity under a “Remove Kebab” slogan, metonymically standing for the removal of Muslims. In March 2019, after the Christchurch attacks, the video was removed from YouTube. At the moment of its removal, it had 9 million views. Nevertheless, it is constantly re-uploaded by other users, and currently dozens of different versions are available on YouTube.

Serbia’s War Criminals in the Great Replacement Theory

The terrorist attack in New Zealand was not the first time that radical right terrorists claimed being inspired by the crimes committed during the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s. Eight years before the Christchurch attack, Andreas Breivik, a radical right terrorist who killed 69 participants from the annual summer camp of Workers’ Youth League on Utøya Island, Norway, published a manifesto under the pseudonym Andrew Berwick, saturated with references to the Balkans and Serbia. The manifesto declares the need to fight against multiculturalism/ left (Marxist political correctness) and the Islamization of Europe – a fight undertaken by him and other members of European resistance movements. He declares that the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) support for Kosovo Albanians during the intervention into Serbia as triggering his actions. The new radical right is developing a narrative of European defence against Muslim invasion, to which Serbia was the first victim, followed by Bosnia, and even more Kosovo, where part of the Serbian lands was taken by Muslims. In this scenario, the loss of Kosovo for Serbia is a threatening sign of what will happen to other European (Christian) countries once they are invaded by Muslims. In Breivik’s own words: “the so-called Bosniaks and Albanians had waged deliberate demographic warfare (indirect genocide) against Serbs for decades. This type of warfare is one of the most destructive forms of Jihad and is quite similar to what we are experiencing now in Western Europe.”[2]

Karadžić, given a life sentence for genocide in Srebrenica in front of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, is in Breivik’s interpretation a true European hero: “I do condemn any atrocities committed against Croats and vice versa but for his efforts to rid Serbia of Islam he will always be considered and remembered as an honorable Crusader and a European war hero. As for the NATO war criminals, the Western European category A traitors who gave the green light, they are nothing less than war criminals.”[3] The Great Replacement theory invents and claims “white genocide” as the main threat Europe is facing, with the possibility of extinction.[4] Within such a perceived battle for survival, it is not surprising that both Breivik and Tarrant – just like Karadžić in the Hague – feel no remorse or guilt, rather they stoically accept legal punishment for their acts of self-defence.

Internet Culture and the Radical Right

The importance of the internet for establishing connections and sharing knowledge amongst radical right groups was readily used since the very dawn of internet. In words of David Duke, one of the most infamous white supremacists, the internet had the power and potency to revolutionize the radical right struggle: “The Internet gives millions access to the truth that many didn’t even know existed. Never in the history of man can powerful information travel so fast and so far. I believe that the Internet will begin a chain re-action of racial enlightenment that will shake the world by the speed of its intellectual conquest.”[5]

Many studies have shown that the internet serves as an important facilitator of communication and organization within the radical right, creating a virtual place of autonomy and a repository of illegal material, to name a few of its important functions.[6] Both Breivik and Tarrant published online, detailed manifestos laying out their ideology while encouraging others to use the internet to spread their message. Breivik’s manifesto calls upon compatriots to spread texts, write blogs, or start Facebook groups, while Tarrant invites them to make memes, as memes did more for the radical right than any other genre. That the worldwide radical right community takes these requests seriously is evidenced by the around 1.5 million attempts to upload the live video of Tarrant’s attack during the first 24 hours after the attack, showing “how much right-wing terrorists have understood social media’s logic of dissemination”.[7] At the same time, these videos serve as a role model for further attacks – similarities like live video stream and explicit references to Breivik and Tarrant earned the Halle terrorist the name Copy-and-Paste-Assassin. Balliet’s computer was full of neo-Nazi material, from Mein Kampf to the video of the Christchurch attack. Amongst these material, memes seem to have a significant place.

Memes

As user generated material, memes are especially equipped for the participatory culture of Web 2.0. Although there is no single definition upon which everyone agrees, Shifman’s explanation of memes as “pieces of cultural information that pass along from person to person, but gradually scale into a shared social phenomenon”[8] neatly captures the relation between individual origin and social consequences of meme sharing. Shifman notes that they are exceptionally suitable for flourishing in the digital media due to originating in individual participation, reproduction via copying and imitation, and easy diffusion through competition and selection. Usually, memes are humorous, funny, provocative, and ironic, often on the edge between black humour, distasteful insults, and hate speech. The transformation of material that is undertaken through the spread of memes rests largely on the unstable meanings of symbols, which are easily combined and rewritten with additional words or images. On the example of Pepe the Frog meme, Cynthia Miller-Idriss shows that even symbols with no relation to the far right could be appropriated by the radical right community, obtaining new meanings and relevance within digital communities.[9] Numerous researchers have looked at the process of appropriation, attempts to defend its meaning, and creativity of users who turned the meme into the radical right symbol worldwide.[10]

Many of the characteristics of memes already addressed in different studies can be identified in the “Remove Kebab” meme. Firstly, the transfer of the meaning from the war in Bosnia, where enemies were, as the song states “Croatian Ustashas and Turks”, to (all) Muslims reveals how irrelevant the original meaning or the context for the meme culture are, as long as there is a usable meaning that needs to be transmitted further. This translation from Balkan enemies to Muslims is achieved via the word “Kebab” – a simple traditional meat dish originating from the Middle East, in Germany often used synonymously with Döner or complementary as in “Döner Kebab.” The word has its own significance within radical right circles – from the National Socialist Underground (NSU) case, which for years ran in yellow press under “Dönermorde”, to the Halle terrorist who killed one of his victims because he was having lunch at a Kebab shop and the terrorist assumed he was a Muslim.

Secondly, the song is a classical war song from the Balkans, raising spirits amongst brothers in arms, as patriotic war songs are supposed to do. It is much less explicit about the predicted battle between Serbs and enemies, while “removal” in the meme clearly refers to physical destruction or expulsion. The humorous attraction of the video is not really clear – one can speculate that it lies in the poor video production, the stoic faces of the soldiers-turned-musicians, the added images of Karadžić drinking coffee, the Eastern melody or trumpets theme at the beginning of the song, or simply the combination of these elements. In any case, the number of shares and comments under the video indicate that users find it extremely funny and a suitable vehicle for their purposes. In different versions, which are constantly uploaded on YouTube and other platforms, the song is available with English subtitles, and translations of the song can be found on different websites.

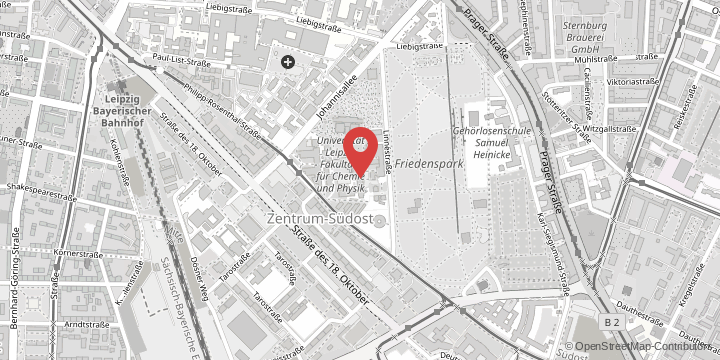

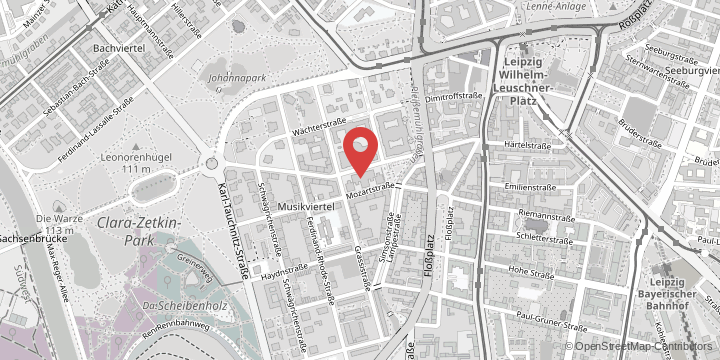

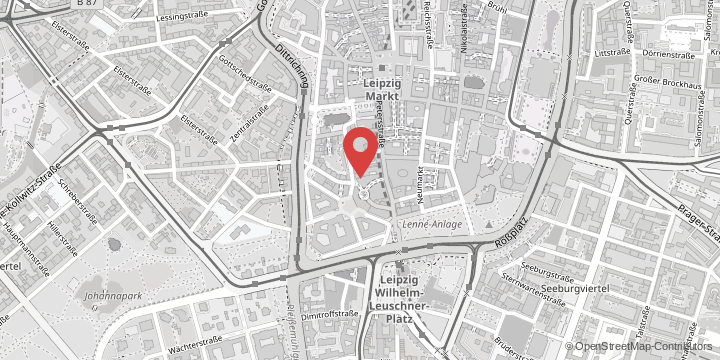

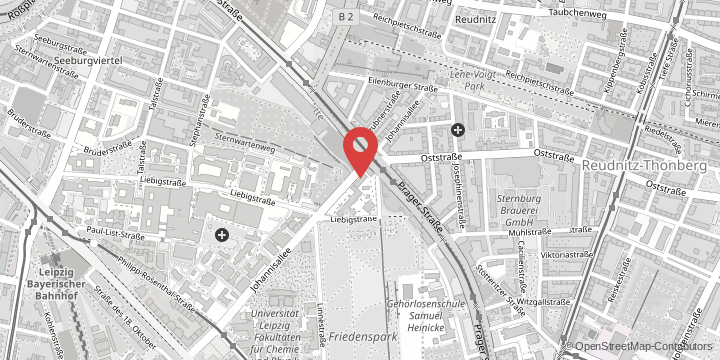

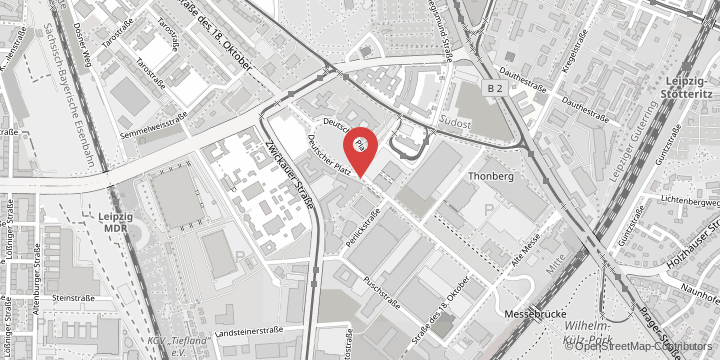

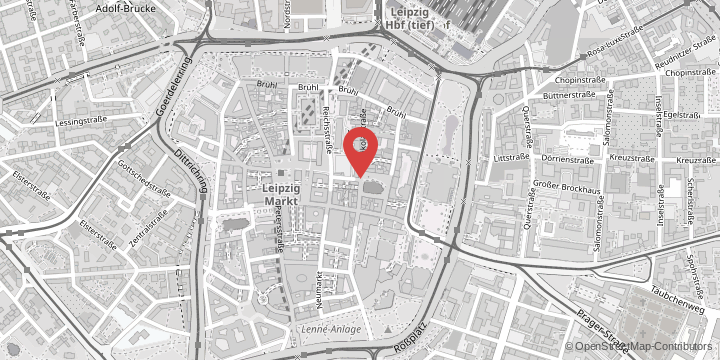

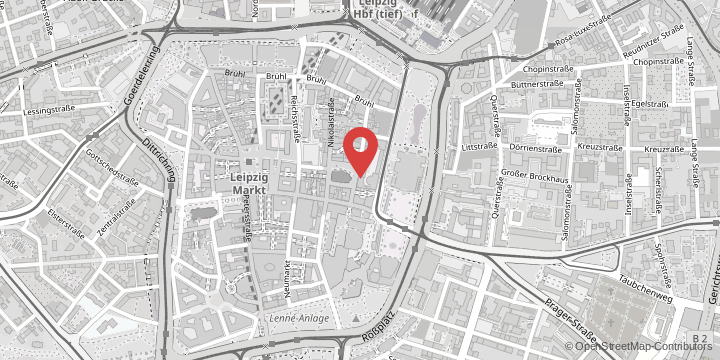

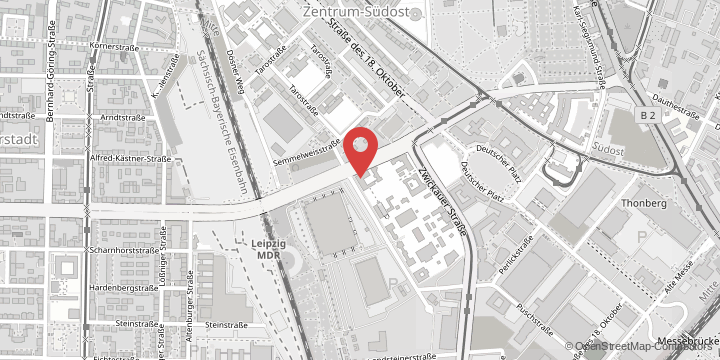

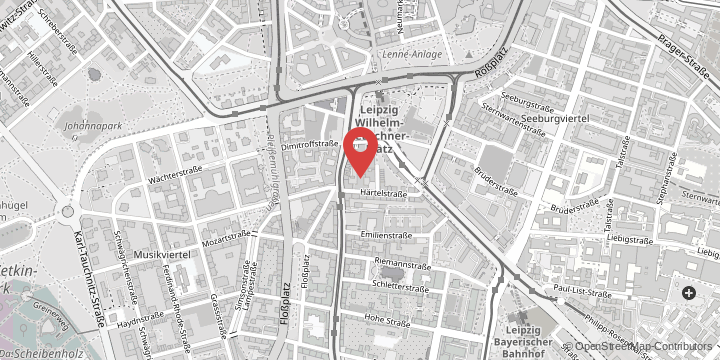

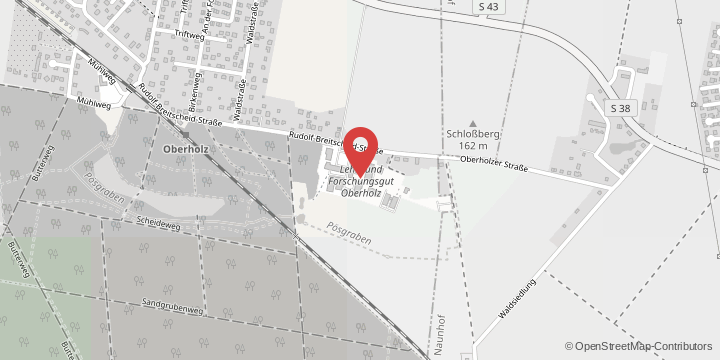

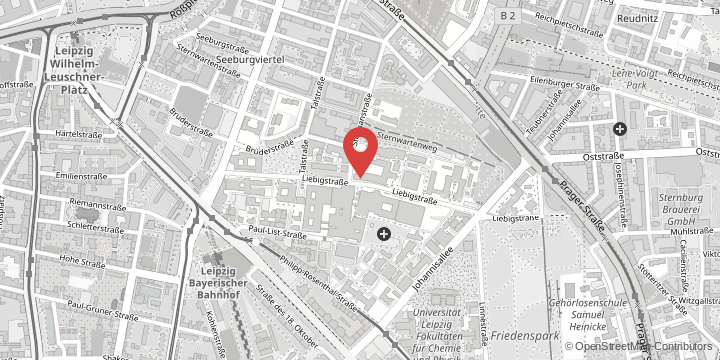

Thirdly, typical visual modifications are provided by users to secure the revival and reusage of the meme. Some of the most common uses are a “dat soldier”[11] face (image 2), historical references (image 3), reviving icons in historical photography[12] (image 4), transforming images in game aesthetics, and using cartoon heroes or different cartoon references (image 5). Finally, there are several counter memes, where users are challenging the message by inserting images of Bosniak victims in the video or adding that “man who drinks coffee” is a war criminal.

Finally, memes are well known for their virtual ubiquity and constant appropriation in different contexts. Under the title "Chinese soldiers singing ‘Remove Kebab’", there is a video of five or six men singing the song with the three-finger Serbian nationalist salute. Although they are struggling with the words and pronunciation, they manage to sing the whole song until the end, even indicating emotional highlights of the song. One can only speculate about the reason Chinese soldiers (if they are Chinese soldiers) are singing this song, or recording and posting it. Although some ammunition can be seen on the video, as well as military uniforms, the insignia is not clear. There are also a number of different videos posted in Greek for example, and some of the comments below the posts indicate perceived “problems” with Muslim minorities in these countries.

In May 2020, in relation to the murder of George Floyd, Chicago police station radio was jammed and the “Remove Kebab” song was played, while the comments under the post on YouTube state “support to police/Trump from Serbia”. The original post, which is meanwhile removed from YouTube had more than 200,000 views and several internet newspaper reporting on it, the Chicago police “Remove Kebab” jam was quickly turned into images and photos that spread across the internet.

Conclusion

Whether the increase of radical right terrorist attacks deserves to be called “a fifth global wave of terrorism”,[13] as suggested by Vincent Auger, the role of the internet in providing what Bennett and Segerberg call “connective action”[14] for the consolidation and mobilization of radical right terrorists seems unquestionable. Visual memory of the Second World War is part of a classical repertoire of symbols used by the radical right on internet, as a number of studies on Pepe the Frog show. Other parts of the radical right narrative and the material it appropriates, like the one from the war in Bosnia, are still not addressed in the research. And the radical right bubble – within which the communication and radicalization amongst warriors, terrorists, sympathizers, and bystanders appear and from which the public gets bits and pieces in moments of violent outbursts – requires much more research employing a global studies approach in order to decipher the local meanings as well as their travelling and appropriation in different contexts.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] I will use radical or extreme right as an umbrella term for ideologically different groups like neo-Nazis, fascists, identitarians, white supremacist, racist, and similar groups.

[2] Andrew Berwick, “2083 - A European Declaration of Independence” (London, 2011), 1407.

[3] Berwick, 1407.

[4] Roger Bromley, “The Politics of Displacement: The Far Right Narrative of Europe and Its ‘Others,’” From the European South Journal, no. 3 (2018).

[5] Quoted in: Jessie Daniels, Cyber Racism: White Supremacy Online and the New Attack on Civil Rights, Perspectives on a Multiracial America Series (Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2009).

[6] Daniel Koehler, “The Radical Online: Individual Radicalization Processes and the Role of the Internet,” Journal for Deradicalization 15, no. 1 (Winter 2014).

[7] Bogerts and Fielitz, The Visual Culture of Far-Right Terrorism, Prif Blog, 31 March 2020, blog.prif.org/2020/03/31/the-visual-culture-of-far-right-terrorism/

[8] Limor Shifman, Memes in Digital Culture, MIT Press Essential Knowledge (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2014), 18.

[9] Cynthia Miller-Idriss, “What Makes a Symbol Far Right? Co-Opted and Missed Meanings in Far-Right Iconography,” in Post-Digital Cultures of the Far Right: Online Actions and Offline Consequences in Europe and the US, ed. Maik Fielitz and Nick Thurston (transcript-Verlag, 2019), doi.org/10.14361/9783839446706.

[10] Jérémie Pelletier-Gagnon and Axel Pérez Trujillo Diniz, “Colonizing Pepe: Internet Memes as Cyberplaces,” Space and Culture, June 14, 2018, 120633121877618, doi.org/10.1177/1206331218776188; Benjamin Krämer et al., “Pepe - Just a Funny Frog? A Visual Meme Caught Between Innocent Humor, Far-Right Ideology, and Fandom,” in Perspectives on Populism and the Media: Avenues for Research (Nomos Verlag, 2020).

[11] Urban dictionary provides the following explanation for “dat soldier”: “An obscure meme of a few Serbian soldiers making horrible yet amusing music. The base for every ‘Remove’ loop.” www.urbandictionary.com/define.php

[12] For this strategy, see Sandrine Boudana, Paul Frosh, and Akiba A Cohen, “Reviving Icons to Death: When Historic Photographs Become Digital Memes,” Media, Culture & Society 39, no. 8 (November 2017): 1210–30, doi.org/10.1177/0163443717690818.

[13] Vincent A Auger, “Right-Wing Terror,” Terrorism Research Initiative 14, no. 3 (2020): 87–97.

[14] W. Lance Bennett and Alexandra Segerberg, “The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics,” Information, Communication & Society 15, no. 5 (June 2012): 739–68, doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661.